The Col. Lyde Griffith Farm (M: 15/27), also known as the Mehrle Warfield Farm, is located at 7301-7307 Damascus Road in Gaithersburg. The current property covers approximately 87.6 acres north of Damascus Road and northwest of Etchison, a rural unincorporated hamlet.[1] The farmstead includes several domestic and agricultural buildings, agricultural fields, and areas in mixed hardwoods. At its March 10, 2010, work session the Historic Preservation Commission voted unanimously to remove the property from the Locational Atlas and Index of Historic Sites and to not recommend designation in the Master Plan for Historic Preservation.

I agree with the HPC’s decision and the reasons stated by individual members for voting against designation. The documentation prepared by staff in support of its recommendation of designation based on the property’s historical associations and architecture was not defensible nor was it accurate and complete. If the HPC had voted to designate the property, all 87.61 acres and individual buildings would have been subject to regulation by the HPC. This brief summary of the property’s history and cultural features derives from research conducted at the Library of Congress. The information presented below underscores the serious questions raised by the HPC regarding the research conducted to support the proposed Upper Patuxent Area Resources Amendment to the Montgomery County Master Plan for Historic Preservation.

Audio (heavily compressed MP3) from the March 10, 2010, work session where the HPC discussed and voted on this property is available here.

Architecture

According to the December 2009 MIHP form completed by staff, the surviving historic house is a “log and frame structure with a three bay, side gable main block.”[2] Staff noted a metal-clad roof, synthetic siding, a rebuilt [brick] chimney, and an attached garage. Most of staff’s description of the property derived from a 1987 survey. At the March 2010 work session staff was unable to answer HPC members’ questions about the house’s integrity nor could staff provide the HPC with a definitive construction date for the building.

Staff wrote in the 2009 MIHP form, “The log and frame house was likely built between 1797, the date of Col [sic] Lyde Griffith’s first marriage to Anne Poole Dorsey and 1809 … The three bay house is a traditional form that was used throughout the region in this era.”[3] Pictures of the home included in the 2009 MIHP form, along with earlier MIHP forms, suggest that the house is a traditional I-house, a common nineteenth and early twentieth century vernacular house type found throughout the eastern United States.[4] The building shown in the photos has a pair of internal gable-end chimneys, a 1.5-story gable roof side (east) addition and a one-story shed roof addition, and a one-story hip-roof garage attached to the building’s rear (north). There are two first-floor windows piercing the west (side) façade. These windows appear to be 1/1 double-hung-sash replacement windows (metal or vinyl). The original three-bay principal façade (south) appears to have a one-story shed roof porch support by wood posts. A photo included in the 2009 MIHP form taken from a distance shows 6/6 DHS windows with wood shutters.

In her report delivered to the HPC at the March 2010 work session planner Sandra Youla described her visit to the property. “We were invited off of the site when we were there so this is the best we can do for you,” reported Youla as she delivered her presentation to the HPC. Youla explained that her departure from the property precluded collecting additional information to present to the HPC.

The dairy barn complex was described at length in the 1987 survey by Andrea Rebeck and in the 2009 MIHP form. In addition to the nineteenth and early twentieth century buildings and structures, there are several late twentieth and early twenty-first century buildings located at this property. These include a large new residence and agricultural buildings and structures related to the active dairy farm.

Landscape

Staff recommended an environmental setting that embraces the entire parcel: “The setting is 87.61 acres, being parcel P909. In the event of subdivision, the features to be preserved include the historic dwelling house, the dairy barn, the Griffith family cemetery, and the vista from Damascus Road.”[5] Staff’s recommendation did not include potential archaeological resources, including the antebellum chrome mines reported to have been operated on Lyde Griffith’s farm.

Historical Significance

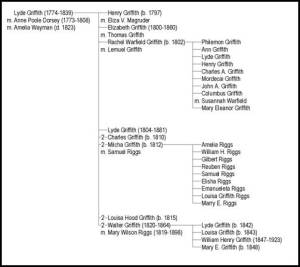

Lyde Griffith (1774-1839) was born into a prominent Maryland family. Engaged in state and local government, large landholders, and military officers in the late Colonial and early Republic periods, the Griffith family’s role in the development of Maryland history is documented in several local histories and genealogies.[6] Lyde Griffith’s father, Samuel, was a Continental Army captain and farmer. Lyde was the only child born to Samuel and his first wife, Rachel Warfield. Lyde Griffith’s first wife, Anne Dorsey, with whom he had three children, died in 1808; he later married Amelia Wayman and they had four children. The Griffith genealogy is complex and warrants further research to tie specific Montgomery County farmsteads to individual descendants and affines in the Warfield and Dorsey families.

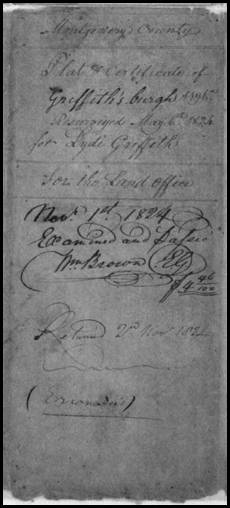

Despite Historic Preservation Office staff’s assertions in earlier documents and testimony that the source of Griffith’s title, “Colonel,” was unknown, several histories identify Lyde Griffith as a captain who served in the 44th Regiment (Montgomery County) during the War of 1812.[7] The Griffiths held extensive lands and relied on African-American labor to work their farms before and after the Civil War. It is beyond the scope of this document to review all of the Griffith Montgomery County landholdings. By 1824, however, Lyde Griffith had accumulated sufficient capital to acquire nearly 1,200 acres which he named “Griffith’sburg” (Griffithsburg).[8]

Chrome Mining

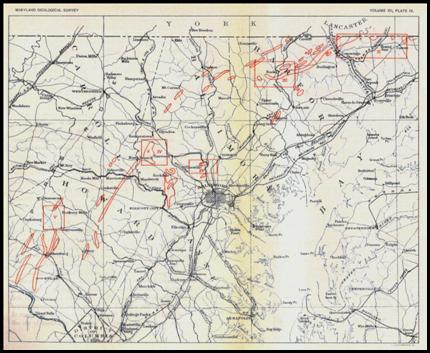

Lyde Griffith’s 1,196-acre farm was located in the Upper Patuxent River drainage and was dissected by several unnamed tributaries. The geology of this area includes serpentine rock formations rich with chrome ore. According to Maryland Geological Survey maps, the serpentine formations near Etchison run from southwest to northeast.[9] Chrome is a mineral that in the nineteenth century was used in the manufacture of steel, the leather industry, and as a pigment. The American chrome industry was founded in the first quarter of the nineteenth century by Baltimore entrepreneur Isaac Tyson Jr. Tyson’s career and contributions to American and Maryland economic history are discussed at length in articles on the chrome industry and in several biographies.[10]

Lyde Griffith appears to have realized by the mid 1830s that his lands held merchantable quantities of chrome. In October 1837 Griffith executed a contract with Washington Waters allowing Waters to remove chrome from the property. According to the contract, Waters, for $50, bought the right to “search for, dig, and remove, as he may think proper, chrome ore or mineral from the lot of ground marked out for him.” Waters also obtained, “the use of the house, except the cellar, in said lot, so long as he may wish it, for the use of the hands he may employ in digging for chrome.”[11]

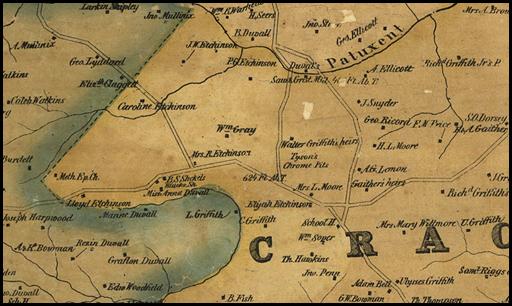

Less than a year into the contract with Waters Griffith apparently began negotiating with Tyson to mine chrome from the farm. These negotiations spurred a breach of contract suit involving Waters and Lyde Griffith’s heirs. Waters was awarded $2,056.25 in damages and Griffith’s heirs appealed the judgment to the Maryland Court of Appeals. The portion of Griffith’s property mined by Waters was a tract formerly owned by Benjamin King and bought by Griffith in 1824.[12] This appears to be the farm that came to be held by Columbus Griffith and which is now south of Damascus Road.[13] Records consulted to date do not indicate if there were chrome pits active within the 89 acres now comprising the Col. Lyde Griffith Farm. The 1865 Martenet and Bond Montgomery County map show “Tyson’s Chrome Pits” in the vicinity of the Col. Lyde Griffith Farm.[14]

The Etchison chrome mines were the only ones active in Montgomery County.[15] The earliest known description of the place where chrome was removed starting in c. 1837 is in a Johns Hopkins University publication from 1889. “On the land of Columbus Griffith, a mile west of Etchison P.O., and a little east of Great Seneca Creek, is a considerable deposit of chromite … This was formerly worked for chrome ore,” reported A.C. Gill. Gill also described “old dump –heaps which surround the pits.”[16]

In 1926 geologist Earl Shannon wrote in the Journal of the Mineralogical Society of America:

An old chromite mine near Etchison in Maryland has been mentioned by Gill as a locality for chrome tourmaline and fuchsite and the present writer has recently described a green margarite from this region. The mine now consists of a shallow depression surrounded by dumps, somewhat overgrown with briars. The only rock exposed in place is a mass of rusty talc in the pit. Beneath this talc outcrop is an old tunnel which still shows a narrow opening but, since no light was available, this was not explored.[17]

Two years after Shannon’s article was published, Joseph Singewald wrote on the Chrome Industry in Maryland in a report published by the Maryland Geological Survey and he described the “Etchison Mine”:

On the farm of Columbus Griffith three-quarters of a mile west of Etchison, chrome ores were mined off and on several times prior to the Civil War and hauled to Woodbine for shipment. There appears to have been three openings. The largest and only accessible one shows no evidence of chrome ore. It consists of a pit 30 feet in diameter and 15 feet deep from which a gallery runs with a steep down grade for 50 feet N. 20° W. and then turns N. 70° E. for 30 feet. The country rock is a soft talcost schist with the direction of N. 70° W. 30° N. A second opening 80 feet distant in the direction N. 35° E., and a third 50 feet N. 75° E. of the second are now completely filled up but small dumps about them contain serpentine in which there are metallic particles but no pieces of massive chromite could be found. The indications are that not much ore was produced here. [Endnote did not copy: Singewald, “The Chrome Industry in Maryland,” 191.]

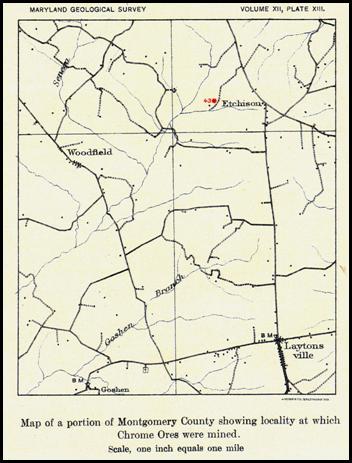

Maryland Chrome Mines. Map published by the Maryland Geological Survey in 1928. The 1928 color plate appears to have been derived from maps created as early as 1919 and published in articles on Maryland's chrome industry.

Singewald’s article also contained a map precisely locating the Etchison mine :

The documents available suggest that the chrome extraction occurred on portions of the former Lyde Griffith property outside of the boundaries of the farmstead now known as the Col. Lyde Griffith Farm. Aerial photographs and United States Geological Survey topographic maps, along with the 1865 Martenet and Bond map, suggest that the wooded portions now within the Col. Lyde Griffith Farm could have been exploited for chrome. These areas require an archaeological evaluation to determine if chrome was extracted in this portion of the former 1,196-acre Griffith property.

Griffith Family Cemetery

Although there appears to be no evidence of the Griffith family cemetery visible, the graves may still be intact and their location delineated using non-destructive archaeological methods (e.g., ground penetrating radar, surface survey, etc.).

Griffith Family Cemetery. Photos included in 1973 MIHP form on file with the Maryland Historical Trust

Other Archaeological Components

Historical photographs and earlier MIHP forms show a large Pennsylvania German bank barn at the farm. Demolished after the farm was first surveyed by M-NCPPC, the barn and its associated yard area may contain significant archaeological data that could amplify and expand the surviving historical record. Furthermore, in addition to the surviving I-house, other domestic buildings may have been located within the current property’s boundaries. These buildings may have been occupied by Griffith family members or by agricultural and industrial (mine) workers. Privies and other outbuildings, if preserved archaeologically, also could contribute to a more complete understanding of Lyde Griffith and his heirs through the architecture they preferred and the objects made and bought, used, and discarded at the farm through time.

Bank barn, privy, and other buildings and structures photographed by M-NCPPC historian Mike Dwyer in 1973.

NOTES

[1] Clare Lise Kelly and Rachel Kennedy, Etchison, Maryland Inventory of Historic Properties Form, November 2009.

[2] Clare Lise Kelly and Lorin Farris, Col Lyde Griffith Farm (M-15/73), Maryland Inventory of Historic Properties Form, December 2009.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Henry H Glassie, Pattern in the Material Folk Culture of the Eastern United States (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1969); Henry H Glassie, Vernacular Architecture (Philadelphia: Material Culture, 2000); Henry H Glassie, Folk Housing in Middle Virginia: A Structural Analysis of Historic Artifacts, 1st ed. (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1975).

[5] Sandra Youla and Clare Lise Kelly, Staff Report. Staff Draft Amemdment to the Master Plan for Historic Preservation: Upper Patuxent Area Resources, January 13, 2010, 3-4.

[6] Joshua Dorsey Warfield, The Founders of Anne Arundel and Howard Counties, Maryland; a Genealogical and Biographical Review from Wills, Deeds, and Church Records (Baltimore: Regional Pub. Co, 1967); Emily Griffith Roberts, Ancestral Study of Four Families: Roberts, Griffith, Cartwright [and] Simpson (Terrell? Tex., 1939); Maxwell Jay Dorsey, The Dorsey Family: Descendants of Edward Darcy-Dorsey of Virginia and Maryland for Five Generations, and Allied Families ([Urbana, Ill.?: M.J. Dorsey, 1947).

[7] “He was called ‘Colonel Griffith’ too. We haven’t been able to determine why. Perhaps it was a term of respect for this gentleman but we don’t know exactly why,” Clare Lise Kelly, Worksession to consider the Staff Draft Amendment to the Master Plan for Historic Preservation: Upper Patuxent Area Resources (Silver Spring, Md, 2010). The MIHP form completed by staff states, “Perhaps he served in the War of 1812,”Kelly and Farris, Col Lyde Griffith Farm (M-15/73). William M. Marine, The British invasion of Maryland, 1812-1815 (Hatboro, Pennsylvania: Tradition Press, 1965), 305; General Society of the War of 1812, Register of the General Society of the War of 1812 (Washington, 1972), 308.

[8] Staff wrote that Griffith patented the tracts in 1826.Kelly and Farris, Col Lyde Griffith Farm (M-15/73). Although the land patent was filed in 1826, earlier survey documents show that Griffith began laying out his Griffithsburg tracts in late 1824.

[9] Joseph T. Singewald, “The Chrome Industry in Maryland,” Maryland Geological Survey Reports 12 (1928): 158-191.

[10] Collamer M. Abbott, “Isaac Tyson, Jr.: Pioneer Industrialist,” The Business History Review 42, no. 1 (Spring 1968): 67-83; William Glenn, “Biographical Notice of James Wood Tyson,” Transactions of the American Institute of Mining Engineers 31 (1902): 118-121; Johns Hopkins University, Maryland, Its Resources, Industries and Institutions (Baltimore: The Sun Job Printing Office, 1893); William Glenn, “Chrome in the Southern Appalachian Region,” Transactions of the American Institute of Mining Engineers 25 (1896): 481-499; Joseph T. Singewald, “Maryland Sand Chrome Ore,” Economic Geology 14, no. 3 (May) (1919): 189-197; Singewald, “The Chrome Industry in Maryland”; United States National Museum, Report upon the condition and progress of the U.S. National Museum during the year ending June 30 … (G.P.O., 1901), 249; “Maryland’s Geologic Features: Soldiers Delight Serpentine Barrens, Baltimore County,” http://www.mgs.md.gov/esic/features/soldiers.html.

[11] Washington Waters vs. Lyde Griffith, Executor of Lyde Griffith, deceased, 2 Maryland Reports 326 (1852).

[12] Montgomery County Land Records. Liber X, folio 497, Benjamin King to Lyde Griffith.

[13] In 1879 Lyde Griffith (descendant) had Griffithsburg resurveyed and the King tracts are clearly shown in the southern portion of the original Griffithsburg survey.“Resurvey on Part of Griffithsburg,” May 8, 1879, Maryland State Archives.

[14] Simon J. Martenet, “Martenet and Bond’s Map of Montgomery County, Maryland” (Baltimore: Simon J. Martenet, 1865).

[15] Additional research in Isaac Tyson’s business papers held at the Maryland Historical Society may change this assertion. According to a contract Tyson executed in 1836, he secured the rights to prospect for and remove chrome from lands owned by a Mary Costigan. Montgomery County Land Records Liber BS 7, folio 522.

[16] A.C. Gill, “Notes on Some Minerals from the Chrome Pits of Montgomery County, Maryland,” Johns Hopkins University Circulars, September 1879, 100.

[17] Earl V. Shannon, “Mineralogy of the Chrome Ore from Etchison, Montgomery Co., MD.,” The American Mineralogist 11, no. 1 (1926): 16.

Shortlink for this post: https://wp.me/p1bnGQ-2E

This was informative and well written. Thanks so much. Had no idea about Colonel Griffith and the chrome.

My best,

Noël Johnston

Was this a plantation?

He was an enslaver and he owned more than a dozen slaves.