Shortly after the first Union defeat at Bull Run in July of 1861, federal authorities confiscated James Crutchett’s Capitol Hill property in Washington, D.C. Just a few blocks north of the Capitol, the property occupied much of Square 683, which is bounded by North Capitol Street, C Street, D Street, and Delaware Avenue. It included Crutchett’s home and a factory where he had begun turning out George Washington kitsch made from wood he was harvesting from Mount Vernon.

View Mount Vernon Factory in a larger map

Located across North Capitol Street from the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad depot, Crutchett’s property was strategically situated. The depot’s neighborhood was an area government officials wanted to transform into a massive aid station and quarters for troops entering Washington via the railroad and on foot. That aid station became known first as the Soldiers’ Retreat and later the Soldiers’ Rest. This post explores the brief but interesting history of Crutchett’s Mount Vernon Factory prior to its occupation by federal troops. To catch up on James Crutchett’s background, go to the first post in this series,

The Gas Man, George Washington, and a Magic Lantern.

The actual ownership of Crutchett’s property was in doubt at the time due to persistent money problems and foreclosure proceedings. Although his true intents may never be known, there is no doubt that Crutchett did indeed have a contract to harvest wood from Mount Vernon and he was making things inside the two-story wood frame factory when the Civil War broke out in 1861. Despite being a life-long English citizen, Crutchett always professed affection for his adopted country and after the war began he allowed troops to drill on his property.

Crutchett left no personal papers behind after his 1889 death. Because of his many legal problems and his many efforts to make money from the federal government, he did leave an extensive paper trail from which it is possible to reconstruct key events in his life, from placing a monstrous gas lantern atop the Capitol in 1847 to his Mount Vernon Factory (1856-1861) and the litigation he pursued after the war to be compensated for the loss of an unprofitable business and property seized by creditors, not the government.

Crutchett left no personal papers behind after his 1889 death. Because of his many legal problems and his many efforts to make money from the federal government, he did leave an extensive paper trail from which it is possible to reconstruct key events in his life, from placing a monstrous gas lantern atop the Capitol in 1847 to his Mount Vernon Factory (1856-1861) and the litigation he pursued after the war to be compensated for the loss of an unprofitable business and property seized by creditors, not the government.

Crutchett had credibility problems that had cost him the chance in the late 1840s to light the U.S. Capitol and which led to him becoming an employee of the Washington Gas Light Company instead of the entrepreneur profiting from lighting the streets of Washington. In the 1850s, he found a partner in John A. Washington, George Washington’s grand-nephew and the last private owner of the late president’s estate, Mount Vernon. Washington was struggling to pay for the estate’s upkeep and by the mid-1850s, much of the property was in disrepair.

Washington (1820-1861) and Crutchett struck a deal that both hoped would improve their financial circumstances. In July of 1852, the two executed a contract giving Crutchett the rights to, “all the timber, trees, shrubs, and wood of all and every kind” in 57 acres within the estate plus 300 trees near Washington’s tomb and near the “residence of the late General George Washington.” In return, Washington was supposed to get $12,000.

The original contract has not survived, but it was transcribed and introduced as evidence in Crutchett’s suit against the United States for destroying his business during the Civil War occupation of his property. Crutchett was allowed to cut roads through the property and could enter at any time to remove the wood for a term of ten years. Washington paid a surveyor to identify the areas where Crutchett could acquire the wood and those maps also were entered into evidence:

The original contract has not survived, but it was transcribed and introduced as evidence in Crutchett’s suit against the United States for destroying his business during the Civil War occupation of his property. Crutchett was allowed to cut roads through the property and could enter at any time to remove the wood for a term of ten years. Washington paid a surveyor to identify the areas where Crutchett could acquire the wood and those maps also were entered into evidence:

1854 plat of parcels in Mount Vernon where James Crutchett was granted rights to harvest wood for his Mount Vernon Factory.

The contract gave Crutchett exclusive rights to the wood and to the use of the Washington name:

There shall be no other timber, trees, or wood sold from the Mount Vernon estate to any person or persons during the ten years said Crutchett is engaged in the removal, working up, or sale of the timber, trees, &c., hereby sold; this is not intended, however, to prohibit the sale of any portion of said estate to the State or the General Government. Said Washington further agrees to certify to the genuineness of the sale and growth of said timber, if deemed necessary by Crutchett, for his interest and at his expense, by a suitable certificate.

Crutchett’s business papers are long gone but it does appear that he maintained detailed accounting records. In the winter of 1855 he bought hardware, “axes, picks, files, and whet stones” and sent them to Mount Vernon with men he had hired to cut the wood. He invested in a sleigh to haul the wood and he built temporary work sheds and housing for his workers at Mount Vernon.

“I sent men to Mount Vernon to cut timber, make roadways, wharfages, &c., for the convenience of getting the wood from the ground to navigable waters,” Crutchett recalled. Once at the Potomac, the wood was ferried across in the Mary Barker, a boat Crutchett bought specifically for the enterprise.

So why did Crutchett, an English citizen who came to the United States in the early 1840s want to go into the business of making and selling things tied to George Washington using wood from Mount Vernon? He explained his motives in a deposition he gave in 1872:

I thought the citizens of the United States were derelict to the memory of Washington, although I was an Englishman, and I felt an interest from the time the first foundation stone of the monument slipped through the bridge over the canal. Mrs. Hamilton was a guest of mine two years at the time I asked permission to remove that stone and place it down in the foundation of the monument. George Washington Parke Custis came over with the speaker of the House of Representatives, John Quincy Adams, and escorted Mrs. Hamilton from my house to see the laying of the foundation stone. I could not but have felt an interest in it beyond that. That is why I undertook it after long thought thinking it would please the public to have mementoes [sic.] of Mount Vernon wood representing the memory of George Washington.

Eleven years earlier, after the government seized his property, he also tried to explain his reasons for setting up the business in a September 1861 petition (PDF) he sent to President Abraham Lincoln:

The undersigned would most respectfully represent, that, a little over seven years since, he entered on a business undertaking, in view of ultimately aiding the building of the “Washington National Monument,” and also the purchase and restoration of the “Home of Washington.”

By the time Crutchett had embarked on his Mount Vernon venture, the nation had been caught up in a cult of Washington. The late president had been fully transformed into a legendary hero and was being commodified in the fine arts and in an emerging American popular culture. Crutchett’s enterprise was launched less than a decade after work was begun on the Washington Monument and the same year that Ann Pamela Cunningham founded the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association.

Crutchett further explained in his letter to Lincoln,

The detail of my undertaking was, the conversion of said Mount Vernon wood into interesting “Mementos” of Washington and his home, thus: The production of the finest engravings and Medallions, executed by the most accurate and skillful artists of America and Europe, showing different views pertaining to Washington and his homes, from the Birthplace to his tomb, also likenesses of himself, and some of his associate patriots, and framing those in moulded and other frames, all of wood from Mount Vernon; also canes, mouldings, bracelets and ear-rings, (gold mounted,) rulers, inkstands, and other interesting and useful articles, each accompanied with three certificates of its genuineness …

Crutchett set about producing these items in a factory he built at the corner of North Capitol Street and D Street N.E. The two-story wood frame and wood-clad Mount Vernon Factory was approximately 40 feet wide and 120 feet long. The factory was outfitted with a boiler, steam engine, saws (upright and circular), lathes, planing and moulding machines, and stampers. A printing press churned out the engravings which were mounted in wood frames.

Soldiers’ Rest. The Mount Vernon Factory is inside the blue box. National Archives and Records Administration.

The Soldiers’ Rest and James Crutchett’s Mount Vernon Factory. Adapted from Lithograph by Charles Magnus, c. 1864. Library of Congress image.

Crutchett built the factory after executing the contract with Washington, in 1855 or 1856. He began operations in the early part of the winter in 1856, according to his 1872 testimony. The factory ran intermittently from 1856 until the time it was seized July 24, 1861. Nothing was produced in its first year of operation and only a few canes were manufactured in 1857. Afterwards, Crutchett began turning out the commemorative medallions, picture frames, and other objects.

Print under glass mounted in Mount Vernon wood. Produced at the Mount Vernon Factory. Adapted from Images posted at Stacks Auction House <http://legacy.stacks.com/Lot/ItemDetail/190845>.

The business was not profitable. Crutchett only grossed about $4,423 between 1856 and 1861. His objects were sold be dealers in New York and Boston. And, they were sold in Washington. Samuel P. Bell, a U.S. Patent Office machinist, allowed one of his employees to “keep a small case for exhibiting and selling some of the articles made by Mr. Crutchett at the Mount Vernon Factory.” Bell estimated that about 400 to 500 items were sold.

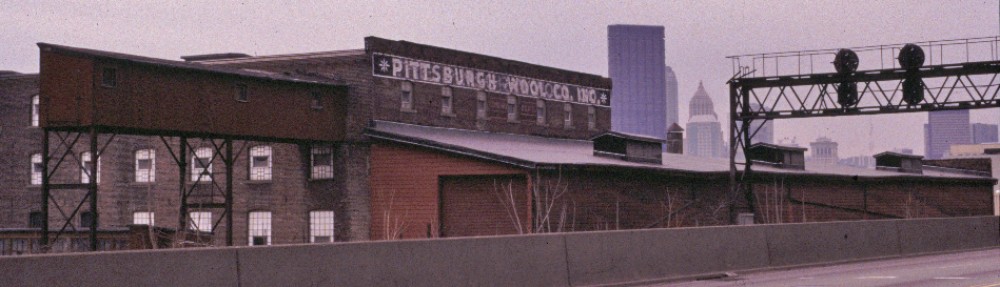

Undated photo of the former Mount Vernon Factory. Original in the Chicago Historical Society collections. Copy located in the James M. Goode Collection, Library of Congress.

For the most part, however, it appears that Crutchett made very few items compared to the quantity of wood he removed from Mount Vernon. He blamed the fitful start on suppliers and on the difficulty of getting the wood ready for production. Much of the wood Crutchett harvested from Mount Vernon appears to have been allowed to rot or was used or destroyed by federal troops after the property was seized in 1861. The factory never resumed production and Crutchett went back to the gas industry. It appears that the factory was demolished around the turn of the twentieth century.

As with his efforts to secure a contract to light the U.S. Capitol and to install gas street lights throughout Washington, Crutchett’s reputation as a charlatan and con man was prominent in the legal battle he waged against the government for compensation (the subject of a future post). Witnesses testified that Crutchett had a reputation for lying and for not paying his bills. Government attorneys in 1872 summed up their assessment of the Mount Vernon business and Crutchett’s character:

When the military took possession of this factory, the claimant was hopelessly bankrupt, and his business, if it ever existed, at an end. His expectations of realizing a fortune from his absurd scheme of furnishing the American people with mementoes of Mount Vernon and completing the Washington Monument, were plainly visionary before the outbreak of the war, and after the great conflict began, he must have been insane [sic.] who could have deluded himself into believing that such an enterprise was then likely to prove successful.

Crutchett’s Washington kitsch occasionally appears on E-Bay and other online auction sites. Some of it is curated in museums. It is clear that he kept some of the items after the war because in the early 1880s he approached the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association with yet another scheme to sell at Mount Vernon “a variety of medals and pictures commemorative of Washington and his home.” Crutchett was politely rebuffed: “Applications of this sort are not infrequently made, but the objections to such arrangements are so positive, that the proposition was declined.”

Mementos of George Washington his birth place, Mount Vernon & tomb. 1881 ad placed by James Crutchett to sell remaining items. Library of Congress image.

George Washington’s monument ultimately was completed in 1888. As for Mount Vernon, in 1858 the property was bought by the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association in a move widely credited as the birth of historic preservation in the United States. James Crutchett, on the other hand, became a forgotten footnote in American history despite his Forrest Gump-like capacity to appear at critical times in the capital’s history.

The next installment in this series will document the seizure of Crutchett’s property after the Union defeat at Bull Run in July of 1861 and the creation of the Soldiers’ Rest. Look for it here on July 24.

Previous entries in this series:

1. The Gas Man, George Washington, and a Magic Lantern

2. Civil War Lost and Found: Lincoln’s First Inaugural Ballroom

© 2011 David S. Rotenstein. The material in this post is derived from an article in progress. Research to produce the article was conducted at the National Archives, Library of Congress, University of Maryland, and the Washingtoniana collection of the D.C. Public Library. Sources and citations will appear in the article.

Shortlink for this post: https://wp.me/p1bnGQ-11F

This is very interesting information. I have a walking stick, seemingly made of sycamore, possibly a souvenir cane from Mount Vernon. It has an impressed mark and a warrantee number. Would one of Crutchett’s canes have had this?

If anyone can tell me, I’d be most grateful.