This terrific New York Times photo became a meme and went viral on the Interwebz. It shows what appears to be a gargantuan Holstein cow — Knickers — dwarfing an adult human.

The accompanying article is a funny piece that digs into the photo and how it’s misleading, i.e., folks who have never gotten up close and personal with a Holstein probably don’t know how big they are in real life. Most cityslickers’ only experiences with Holstein cattle come from Gary Larson’s Far Side cartoons, Ben and Jerry’s ice cream art, and the burgers we eat, They know very little about cattle and Holsteins in particular. The NYT article and the folks who know my “thing” with cattle who have shared the image reminded me that I haven’t written much lately about livestock and leather tanning. I think it’s time to fix that situation.

Pittsburgh History cover, Spring 1997 issue, featuring my article on the history of Pittsburghs leather industry.

I spent a lot of years researching and writing about tanning, stockyards, and the interconnected meatpacking and meat byproducts industries. While researching Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania’s tanneries in the mid-1990s I encountered one of those people whose names eerily fit the jobs they do. You know, Mr. Butcher the butcher. Or, Mr. Macro the math teacher. Here in the DC suburbs I always chuckled when I saw a Peed Plumbing truck.

This fun little post is about a Pittsburgh tannery owner named Alexander Holstein (1812-1895). Holstein came to Pittsburgh from Bavaria. He arrived in New York in 1836. Within a decade, he appeared in Pittsburgh city directories as a saddler and harness maker with a shop in Wood Street in the city’s downtown. Wood Street was near the confluence of the Allegheny, Ohio, and Monongahela rivers. Its proximity to to the rivers and to the later Pennsylvania Canal made it an ideal location to become Pittsburgh’s earliest leather tanning district. Hides, tanbark, and water were easily obtained. The same transportation routes made it possible to ship the finished leather not sold locally to eastern markets.

Holstein remained in Pittsburgh’s old tanning and leather district until 1853, when he rented land in Duquesne Borough, a small incorporated community on the Allegheny River next to Allegheny City and opposite Pittsburgh. By the time that the Civil War broke out, most of Pittsburgh’s tanneries had moved out to Duquesne and Allegheny City.

During the last half of the 19th century, two neighboring cities dominated Western Pennsylvania: Allegheny and Pittsburgh. Duquesne Borough, like many of the former municipalities that once defined the greater Pittsburgh region, was a short-lived industrial suburb . More closely tied by proximity and people to Allegheny than to Pittsburgh, Duquesne (incorporated in 1849) was a town defined by processing industries rather than the heavy manufacturing industries that dominated Pittsburgh and Allegheny during its brief two-decade existence. Before its annexation by Allegheny in 1868, Duquesne had developed a significant concentration of tanneries along a narrow strip bounded by the former Pennsylvania Canal and the Allegheny River.

Former Duquesne Borough (after 1868, Allegheny City’s 8th Ward). Tannery sites are shaded; arrow points to Alexander Holstein’s tannery. Source: Atlas of the Cities of Pittsburgh, Allegheny, G.M. Hopkins & Co., 1872.

Close-up of tanneries in 1872.

By 1871, Holstein had transitioned from renting his tannery site to owning several contiguous lots with a siding on the Pennsylvania Railroad. There he operated his Union Tannery until 1888 when he sublet it to James Callery (1833-1889), another longtime Pittsburgh tanner who also owned a nearby large brick tannery.

Holstein tannery during the period it that James Callery rented it. Source: J.W. Leonard, Pittsburgh and Allegheny Illustrated Review: Historical, Biographical and Commercial. A Record of Progress in Commerce, Manufactures, the Professions, and in Social and Municipal Life. Pittsburgh, Pa.: J. M. Elstner, 1889.

Callery renamed Holstein’s tannery the “Lion Tannery,” a complex that included the tanning plant and adjacent structures. “This tannery is a four story building, 100×170 feet in dimensions, and turns out 600 sides of oak harness leather per week,” reported one contemporary observer in 1889. The 1888 lease was for a five-year term and it appears that Holstein regained control of the tannery before his death May 10, 1895.

Holstein tannery, c. 1890. Atlas of the Cities of Pittsburgh, Allegheny, G.M. Hopkins & Co., 1890.

Holstein manufactured mainly harness leather using oak bark to make his tanning liquors. No records survive documenting where he got his hides — many likely came from the many nearby slaughterhouses; others probably came into his tannery by way of the canal, and later, the railroad. Holstein’s oak bark came from the forests north and south of Pittsburgh.

In 1870, Holstein’s tannery processed 1,500 beef hides, 1,400 cords of bark, 2,620 gallons of fish oil, and 600 pounds of lime in his steam-powered tannery. He employed 20 men who produced 3,500 pounds of sole leather and 7,000 pounds of harness leather. A decade later, Holstein processed 11,000 hides and was now using both oak (1,800 tons) and hemlock (240 tons) bark. His operation had expanded to employ 50 men, according to the U.S. Census.

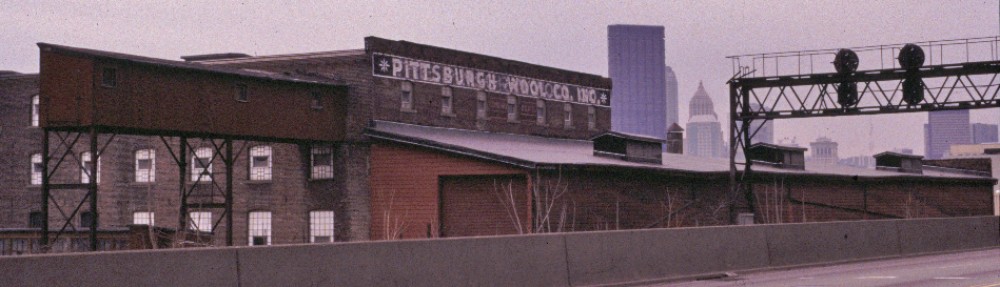

Former Holstein tannery, early 20th century. The tannery was converted into a wool pullery owned first by John Stratman and later by W.P. Lange. The wool pulling business ultimately became the Pittsburgh Wool Company, the last wool pulling business in the United States. Pittsburgh Wool processed its last pelts in 2000.

After he died in 1895, other Allegheny tanners (C.C. Hax, Julius Groetzinger, and Charles F. Kiefer) appraised his estate. Holstein’s tannery had 11,130 sides of leather (worth $47,302) and assorted equipment and fixtures. All told, his tannery assets, cash, and stocks totaled $134,983.35 (about $4 million in 2018).

I haven’t located any pictures of Holstein. His passport applications describe him as a big man: 6’2″. In 1871 he had gray hair, grey eyes, and a fair complexion. He was married to Julia Pryor (1819-1900), a Pittsburgh native. One son, Louis, followed his father into the tanning business and he incorporated the Holstein Tanning Company. A daughter, Kate (1851-1929), married into another Allegheny tanning family, the Lappes. Charles O. Lappe (1846-1916) was a second-generation Allegheny tanner whose father, J.C. Lappe owned a tannery and his uncle, Johann Martin Lappe, owned another.

I don’t know if or how many Holstein hides passed through Alexander Holstein’s tannery. I do know that I have mused about how apt Holstein’s name was for his trade ever since I first encountered him 1996.

Holsteins, California, 1995.

The New York Times, Sunday December 2, 2018, p. 3

© 2018 D.S. Rotenstein

Shortlink for this post: https://wp.me/p1bnGQ-3gw