Moses Order logo, c. 1887.

Peter Paul Brown must be turning in his grave if he knows about the kerfuffle over one of the cemeteries owned by the Black benevolent organization he founded in 1867. The Philadelphia physician who lived between c. 1822 and 1882 established the Ancient United Order of Sons and Daughters, Brothers and Sisters of Moses — the Moses Order — to provide death benefits, healthcare, and other social welfare services for African Americans in a deeply segregated Reconstruction era America. Brown was a skilled entrepreneur and he held tight to his intellectual property and the organization’s name. That name is now the center of a fight over land in suburban Maryland just across the border with Washington, D.C., where activists claim hundreds of bodies are buried beneath a parking lot and construction site.

The site is one of many abandoned and desecrated African American burial grounds throughout the United States for which activists are seeking recognition, protection, and commemoration. One of the best known examples is the cemetery where the African Burial Ground National Monument was established in Manhattan. Massive protests and congressional hearings brought the issue to headlines in newspapers around the nation in the early 1990s.

African Burial Ground Way, New York, New York, 2018.

In 2015, the Montgomery County, Maryland, Planning Department began holding public hearings for a new sector plan in a mostly commercial area in unincorporated Bethesda. Planners disclosed that their research had uncovered the likely site of a historic African American cemetery in their study area. It had been documented in old maps and in a local history book but had been mostly forgotten since the 1960s when heavy equipment excavated much of the site to construct a high-rise apartment building and grade a surface parking lot. None of the graves was professionally excavated to relocate the bodies buried there. Continue reading

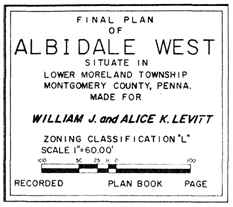

Architectural and cultural historians for decades have been tuned into the significance of the sprawling Postwar suburbs built by Levitt & Sons bearing the family firm’s name. Recent research into other Levitt developments like Belair in Bowie in the Washington, D.C., suburbs has expanded our understanding of the Levitts’ impact on modern cultural landscapes and in shaping American homeownership. Last week while doing some fieldwork in the Philadelphia suburbs I encountered a 1960s subdivision planned by firm president William J. Levitt (1907-1994).

Architectural and cultural historians for decades have been tuned into the significance of the sprawling Postwar suburbs built by Levitt & Sons bearing the family firm’s name. Recent research into other Levitt developments like Belair in Bowie in the Washington, D.C., suburbs has expanded our understanding of the Levitts’ impact on modern cultural landscapes and in shaping American homeownership. Last week while doing some fieldwork in the Philadelphia suburbs I encountered a 1960s subdivision planned by firm president William J. Levitt (1907-1994).