Update: See this later post on the home’s inclusion in a National Building Museum exhibit.

I am slowly getting around to revising my 2010 Vernacular Architecture Forum paper on Silver Spring’s 1939 World’s Fair Home. One of the areas that I was unable to deal with in the VAF paper was how the Silver Spring house differed from the one built in the World’s Fair Town of Tomorrow. This brief post is drawn from my ongoing work.

When Garden Homes, Inc., executed its contract with the New York World’s Fair Corporation to build an exact replica of Demonstration Home Number 15, the Johns-Manville “Long Island Colonial Home,” the developers were required to build a faithful copy. According to the contract, Garden Homes was to “follow exactly” the “plans and specifications used by the Fair Corporation in the construction of House No. 15 of the Town of Tomorrow.”

Garden Homes got some leeway in adapting the original design to the home planned for Silver Spring. For example, since the original Demonstration Home No. 15 had no basement and therefore no heating or hot water appliances, the Fair Corporation allowed Garden Homes to, “use equipment to suit local construction.”

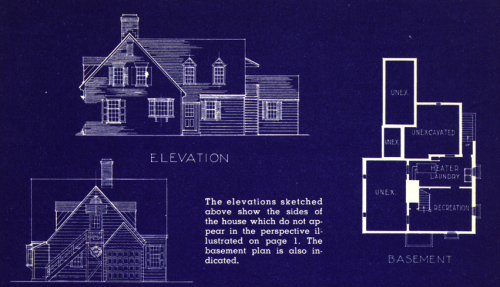

Demonstration Home No. 15. Drawings included in Town of Tomorrow promotional brochure. From the author's collection.

Exterior features that clearly were modified include the building’s footprint and porch railings. Because of the unusual lot size Garden Homes selected for its replica and inadequate rear yard setbacks to construct the rear ell as designed by architects Godwin, Thompson, and Patterson, the garage was brought into the basement level beneath the workshop. Unlike the original Demonstration Home 15, which was built on a level surface, the Silver Spring house was built into a bank. The modifications to the design compressed the footprint fit all of the rooms into the envelope designed by the architects.

Another significant deviation from the World’s Fair original involved modification of the front and kitchen side porches. The Silver Spring home’s front porch was built with metal porch rails instead of wood balusters. Photos show Demonstration Home 15 with wood porch rails, painted white. Because of the lot’s topography in Silver Spring, the rear yard drops significantly and the kitchen side porch is located back far enough from the home’s front plane that steps from the side yard are required to access the door. The original, again because it was built on level ground, had no steps leading to this porch.

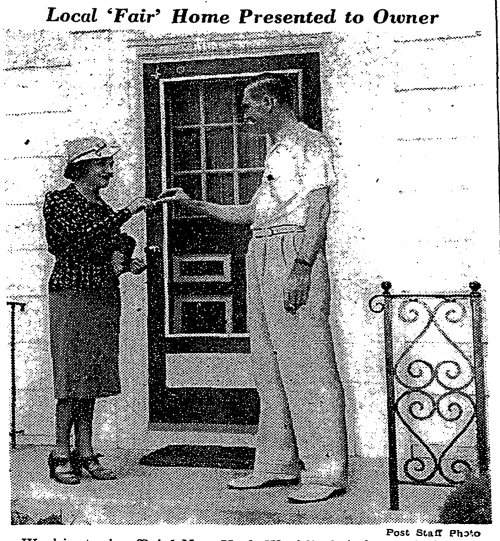

1939 Washington Post photo showing Garden Homes president James Wilson with new homeowner Pauline Scandiffio on the Silver Spring World's Fair Home porch.

There is nothing in the surviving documents that suggests that New York World’s Fair Corporation officials were concerned about the modifications made by Garden Homes. Fair Corporation executives visited the house as it was being constructed and they participated in the carefully staged events leading up to Garden Homes’ opening it up for tours prior to its August 1939 sale to Mario and Pauline Scandiffio. More to come as I move the paper towards publication.

UPDATED: Complete VAF paper abstract added

“The Greatest Publicity Stunt Available to Developers”: Washington’s 1939 World’s Fair Home

ABSTRACT

By 1939 suburban subdivisions were a familiar element in the American landscape. The spurious suburb created in the 1939 New York World’s Fair Town of Tomorrow offered visitors a sampler of tradition and innovation packaged for consumers just beginning to emerge from the depths of economic depression. Shortly before the Fair opened in the spring of 1939 Washington, D.C., subdivider and developer Garden Homes, Inc., secured the rights to use the Fair Corporation’s name and the plans to one of the Town of Tomorrow’s 15 demonstration homes. Designed by New York architects Godwin, Thompson and Patterson and sponsored by the Johns-Manville Corporation, House No. 15, the Long Island Colonial Home, became Garden Homes’ 1939 marketing centerpiece in Northwood Park, the Silver Spring, Maryland, subdivision located less than three miles north of the District of Columbia.

Northwood Park was an ordinary subdivision with modest brick Cape Cod cottages and larger stone Tudor Revival houses marketed to young professionals with new families. Using common real estate trade tools, Garden Homes lured prospective buyers through creatively illustrated and worded display ads hawking Northwood Park’s rustic charm and affordability. The firm used themed models like the Bride’s Home and the Anniversary Home equipped with the latest modern gas appliances; some came with a brand new car in the garage and a supply of groceries. Garden Homes’ ads were packed with multiple meanings to bring middle class doctors, engineers, and government employees into their subdivision. Their most successful marketing vehicle was the “World’s Fair Home” which drew thousands of sightseers and many prospective buyers to Northwood Park in the spring of 1939 during a carefully crafted 120-day marketing campaign.

Using local land records and newspaper archives along with the records of the New York World’s Fair Corporation, this paper explores the vernacular landscape created by Garden Homes between 1936 and 1941 and the social and economic factors that made it possible to construct an ephemeral tourist attraction in one of Washington’s ubiquitous suburban subdivisions. Northwood Park’s World’s Fair Home was built at the intersection of corporate consumer culture and vernacular entrepreneurialism and it was one of many efforts by Maryland and Virginia developers to capitalize on the demand for affordable and attractive single-family homes in proximity to the nation’s capital in what World’s Fair Corporation executives called “the greatest publicity stunt available to developers.”

All content © 2010 David S. Rotenstein.

Shortlink for this post: https://wp.me/p1bnGQ-aj