Sometimes it takes a real kick in the pants to get moving on turning a conference paper into something more. Last week I received an email from a history professor in the UK who is working on a project that parallels some research I presented in draft form at the 2007 Washington Historical Studies Conference. I allowed the National Trust for Historic Preservation to summarize the paper and post a link to a PDF of the entire paper at its President Lincoln’s Cottage Website. I have suggested a collaboration to my colleague across the pond rather than a race to get into print; we’ll see how that goes. In the meantime, I’d like to recapture a little bit of my own intellectual property by reprinting a slightly revised version of the 2007 paper with illustrations.

Capital Craftsman: John Skirving in Washington

David S. Rotenstein

Washington Historical Studies Conference, Washington, D.C., 2 November 2007

Introduction

John Skirving was an architect, artist, engineer, and entrepreneur who came to Washington in the winter of 1839 to heat and ventilate buildings under construction by the federal government. Recognized by his contemporaries as a competent mechanic and skilled designer, Skirving made enduring and wide-ranging contributions to Washington’s built environment and the nation’s aesthetics during the mid-nineteenth century. He is mainly known as a footnote to the architectural history of the farmhouse built for banker George W. Riggs Jr. that has gained fame as the “Lincoln Cottage” on the grounds of the former U.S. Soldiers’ Home. Skirving’s 1842 Capitol Hill cottage played key roles in several chapters of Washington’s history, first as one of the city’s earliest gothic revival homes and later as the first private residence to be lit by gas. During the Civil War the property was commandeered and transformed into the Soldier’s Rest, Washington’s sprawling receiving center for Union troops entering the city.

Lost among various efforts to link the former Riggs farmhouse to prominent architectural pattern book authors Andrew Jackson Downing and Alexander Jackson Davis is the remarkable story of Skirving’s nearly four-decade career in the United States that included work on many of Washington’s landmark buildings and landscapes as well as his undertakings in Philadelphia and other parts of Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia, and New York. This paper explores John Skirving’s life through some of the architectural and artistic work that he did. Skirving’s Washington story is framed by the U.S. Patent Office building. It is the building for which Skirving came to secure work during an economic depression that devastated his Philadelphia business and it is where the last of his grand artistic projects hangs in the National Portrait Gallery.

Philadelphia

Twelve years before he came to Washington looking for federal contracts, John Skirving (1804-1865) arrived in Philadelphia on ship from Liverpool. The twenty-four-year-old Englishman was a master bricklayer by the time he had arrived in May of 1827. Philadelphia during the first three decades of the nineteenth century produced – and attracted to practice – some of the nation’s leading incipient architectural professionals, among them William Strickland, John Haviland, Benjamin Henry Latrobe, Robert Mills, and Thomas Ustick Walter, himself the son of a master bricklayer. The builder-architects who called Philadelphia home during this time found a fertile educational and entrepreneurial environment in which to hone their skills and bond them in business and in wood, bricks, and mortar.[1]

Less than a year after arriving, Skirving bought several lots in Philadelphia’s Old City and in the city’s Spring Garden district. He was joined in March 1828 by his wife, Ann, and their newborn son, James. Skirving made Willings Alley between Walnut and Chestnut streets the site for his home and his workshop. Little evidence survives of Skirving’s first few years in Philadelphia. During those early years Skirving worked on a variety of construction projects that are renowned as architecturally significant and he benefited greatly by his introduction to master architects. Among the buildings he worked on were Moyamensing Prison under Thomas U. Walter as well as the Philadelphia Navy Yard and the Merchant’s Exchange under William Strickland.

Skirving’s earliest surviving architectural drawings are a pair of perspectives he submitted in February 1833 in the competition to design and build Girard College. Submitted late in the competition and not likely seriously considered, Skirving’s designs were eclectic and drew heavily from a classical vocabulary.[2] His entry was among a wide-ranging field that included overreaching house carpenters and established masters, including Strickland, Walter, Haviland, and Ithiel Town. Ultimately, it was Walter’s design that won the contract.

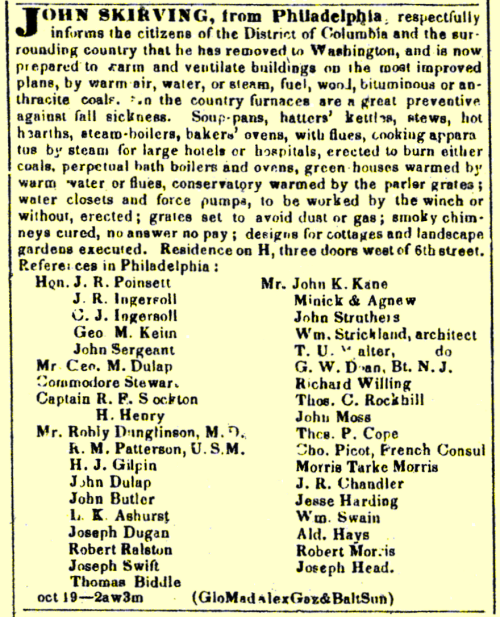

As a designer of buildings, Skirving’s impact in Philadelphia was minimal. Surviving documents suggest that he was an entrepreneur who carved a comfortable niche working as a contractor specializing in heating and ventilation, designing and building furnaces and other infrastructure . His arrival in the United States appears to coincide with his decision to pursue this specialization. “For the last 12 years I have been ingaged [sic.] in warming & ventilating buildings,” he wrote in an 1841 letter to the Commissioner on Public Buildings in Washington.[3]

Skirving’s clients in the 1830s included other Philadelphia architects and builders as well as iron makers – notably Wistar Morris and Stephen Tasker – and New York’s Jordan L. Mott, inventor of the anthracite burning stove. In addition to his building work, Skirving sold stoves, needles, and cookware manufactured by Morris and others. He also worked for several years as a superintendent for French exile Joseph Bonaparte at Bonaparte’s Bordentown, New Jersey, estate.[4] Nights and in the off-season winter months he spent time painting watercolors and designing such things as ventilation systems for ships and mobile bake ovens. His paintings of landscapes and buildings were exhibited in various Philadelphia venues, including the Artists Fund Society, the Pennsylvania Academy, and the Franklin Institute. None of these early canvases appears to have survived into the twenty-first century.[5]

In 1831 Skirving’s newly married brother-in-law, Edward Lyons (1803-1857) moved to Philadelphia from England. Lyons likely worked in the textile industry while in England and in Philadelphia he went to work for Skirving, apparently learning the building trade becoming a bricklayer himself and working in Skirving’s Philadelphia shop. As kin, friends, and business associates Lyons and Skirving forged a close bond. Letters between Skirving and Lyons, plus Lyons’s diary provide some of the richest details of Skirving’s personal and business lives. They illustrate a persistent, funny, and creative person who would rather travel and paint than toil with the daily demands of running a business.

Skirving possessed all of the assets to succeed as an entrepreneur in Philadelphia’s building trades. He had developed a sound reputation as a skilled mechanic and he had the capital to extend credit to his clients and others. He used his profits to travel widely for recreation and to study the works of others in buildings throughout Europe. His friend Thomas U. Walter observed of Skirving in an 1860 letter, “He has been abroad, and has made good use of his opportunities for self improvement.”[6] To support his pending 1841 proposal to ventilate the Capitol building, Skirving himself touted his 1830s travels to Europe to study building ventilation techniques: “I have visited Europe twice during the last 8 years for the purpose of examining the various plans used in London &c.”[7]

Today we take for granted the comfortable temperatures, clean air, and well-lit interior spaces of our homes and workplaces. English engineer David Reid perhaps overstated things when he wrote in 1844 that “the great and primary object of architecture is to afford the power of sustaining an artificial atmosphere.”[8] Reid’s pathbreaking 1830s ventilation system in the English House of Commons set the standard for ventilating large public buildings and it was the benchmark by which efficacy and cost were measured during the mid-nineteenth century. Skirving fortuitously arrived in Washington less than a decade after Reid’s system was unveiled and at a time when Congress was vigorously debating the poor air quality inside the Capitol. In 1842, the House Committee on the Public Buildings and Grounds attributed – somewhat amusingly from a twenty-first century vantage point – irritability, diminished mental faculties, and other ills among legislators to the House chamber’s poor air quality. “Some of the distinguished men of our country have fallen in death during an intellectual effort,” wrote committee chairman W. W. Boardman to underscore the dire situation.[9]

In the years leading up to the first of many nineteenth-century congressional decisions to improve the Capitol’s heating and ventilation, events were unfolding that would push Skirving away from Philadelphia and pull him towards the Capital City. The fire that destroyed the Patent Office in 1836 and initiatives to build other public buildings and homes for a growing population spurred an unprecedented building campaign that drew artisans and laborers from around the world to the District and provided mostly steady work for increasing numbers of native Washingtonians already in the building trades. The carpenters, bricklayers, and stonemasons who worked under contract to the Commissioner of Public Buildings were skilled mechanics and entrepreneurs whose client base included merchants, bankers, politicians, doctors, manufacturers, and military officers.[10]

When the nation’s economy teetered during Panic of 1837 and failed in the depression of 1839, thousands of entrepreneurs found themselves with mounting debts, failed businesses, and in federal bankruptcy court.[11] Washington, however, continued to grow and the various public building projects were an attractive solution for someone like John Skirving who was seeing his entire economic world come undone around him. He was able to survive the 1837 downturn, but as specie became little more than colored paper he expressed surprise and concern in letters to Edward Lyons who was prospecting for lead in Wisconsin. “Philadelphia is strangely altered. Since you left there is little or nothing doing although I have no reason to complain so far but prospects are bad the last week,” Skirving wrote in July 1837.[12] The iron manufacturers with whom Skirving did business had suspended their works or dramatically reduced their workforces to cope with the constricted economy.

Panic and Prospecting: Washington

Skirving rebounded along with much of the economy in 1838. He completed furnace and boiler construction projects in Philadelphia and West Chester, Pennsylvania, Princeton, New Jersey, and Wilmington, Delaware. He boasted in a September 1838 letter to Lyons, “I have a first rate season.”[13] It was a brief respite before the crippling 1839 depression. By April of 1839, Skirving had begun to borrow money and lay off much of his workforce. And with Philadelphia’s economic outlook dim and his resources shrinking, later that year Skirving approached his friend, architect William Strickland, to write an introduction to Robert Mills to assist Skirving in bids to solicit work with the federal government. “I have known Mr. Skirving for a long time and have no hesitation in assuring you of his qualifications as a mechanic and as a man in whom you may have the utmost confidence,” Strickland wrote in December 1839. “He has been very successful in all his attempts in constructing furnaces and ranges of every description and the utmost dependence may be placed upon him in whatever he undertakes in his profession.”[14]

Skirving successfully landed several contracts to work on various public buildings under construction in the late 1830s and early 1840s. While Skirving was building his Washington portfolio, his Philadelphia business continued to deteriorate. Still having difficulty collecting on his debts, including one for more than $111 thousand, Skirving began selling properties in the city on which he had constructed brick buildings. He also found himself in the unenviable position of informing Edward Lyons, whom he had convinced to return to Philadelphia the year before, that their business plans were not going to work out. The letter Skirving wrote to Lyons May 1, 1840, provides the clearest picture of the circumstances that drove Skirving to Washington and it is worth quoting at length:

This is a painful step as much to me as it will be to yourself. I believe for the last 12 months I have been going behind and I see no other prospect without some exertion & retrenchment – being in debt & no available means of getting out …

… I have been in hopes that things would mend. I see no prospect and I am prospecting at Washington …

… I don’t wish that we should part. I am afraid to say even I see no way that we can get along but by your taking the place of a laborer & at the same wages. You know as well as anybody the cause of the badness of the times therefore it is useless for me to say more.[15]

Between 1840 and 1842, Skirving traveled regularly between Philadelphia and Washington, where he rented accommodations while in town for work. The mounting financial pressures in Philadelphia and increasingly lucrative federal contracts spurred Skirving to move his family to Washington. As a poor credit risk Skirving was unable or unwilling to buy property, so his wife Ann, in November and December 1842, purchased two lots on Capitol Hill on the northeast corner of North Capitol and C streets. Within a year, the family was living in a 2.5-story wood frame cottage Skirving built. It joined the Riggs cottage as one of Washington’s earliest Gothic Revival cottages and it received widespread attention: “Mr. Skirving’s English cottage on Capitol Hill, is one of the neatest specimens of rustic architecture I have seen. His portfolio is enriched with some beautiful designs,” wrote one newspaper in 1844.[16]

John Skirving's 1842 Capitol Hill Cottage. Early 20th century photograph courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Also in 1842 Skirving became involved with Washington carpenter William H. Degges and the son of a District brickmaker and bricklayer in the design and construction of a new farmhouse for George W. Riggs Jr. There is no way to know how John Skirving and William H. Degges met. They were among the many skilled builders working on the monumental buildings under construction in Washington after 1837. Degges senior and Skirving were both bricklayers by training; Skirving and the two Degges worked in close proximity in the construction of the Patent and Post Office buildings; and, Skirving and William H. Degges both worked on the construction of the Treasury building. Any of the public and private construction projects active in Washington between 1840 and 1842 could have brought the pair together.

The collaboration came near the end of the depression and it was made possible by the bankruptcy of John Agg, a Riggs family friend. In June 1842, Riggs bought Agg’s farm in the hills overlooking Washington and the following month the banker hired Degges to design and build a new house. Degges drew up the “Specifications of materials and workmanship, of a house to be built for Geo. W. Riggs on his farm near Rock Creek Church.”[17] The July 23, 1842 specifications called for a two-story brick house. All carpentry and masonry work was detailed, from the width of each wall to the types of brick, wood, glass, and hardware to be used. One brief passage in the three-page document provides the sole surviving documentary link between Degges and Skirving: “Verandah on South side according to plan given by M John Skirving.”[18]

While Degges was a competent builder, he lacked Skirving’s experience and skills in architectural and landscape design. American architectural pattern book authors like Alexander Jackson Davis and Andrew Jackson Downing relied heavily on the aesthetics and vocabulary of the built environment popular in England during the first half of the nineteenth century.[19] In Skirving, Degges and Riggs had a living thread tied to the source of the contemporary domestic architects popularizing and adapting English templates to the American landscape.

The George W. Riggs farmhouse (left) and the U.S. Military Asylum (Soldiers' Home). 1860s image from the collection of Edward Steers.

Skirving’s architectural design work in the early 1840s had garnered attention with his prominent Capitol Hill house. Many of his colleagues in architecture and art recognized his capabilities and they frequently recommended his services. American realist painter George Caleb Bingham (1811-1879) wrote to his friend Missouri politician James Rollins in 1853, “I send you a hasty pen sketch of the ground plan and elevation of a building, furnished to me at a minutes notice, by an English friend of mine, Mr Skirving.” Rollins was contemplating enlarging his house and Bingham had mentioned this to Skirving while in Washington. “Mr S. has a very fine taste in rural architecture and I think the design appended, tho’ hastily drawn, remarkably simple as well as picturesque,” Bingham added.[20] One 1840s detractor, however, after seeing a perspective of the proposed Smithsonian Institution Skirving prepared for Robert Dale Owen suggested that “he was an amateur in such matters, and that his faculty lay in the use of such tools as houses are built not designed with, especially in that most important one in all building erections, the trowel.”[21]

The Skirvings lived briefly in their Capitol Hill home, selling it in 1845 to self-styled engineer and lighting entrepreneur James Crutchett, who is best known for mounting a gas lantern ninety-two feet above the Capitol dome in 1847. Crutchett’s lighting system was perfected in a plant he built the basement of the former Skirving house, which he renamed “Bethel Cottage,” and which was illuminated inside and out by gas.[22] Between 1845 and 1850 John and Ann Skirving, their two daughters and younger son John lived at times in Washington, New York City, Camden, New Jersey, and Philadelphia. The Skirving’s daughters went off to the Moravian Female Seminary in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania; son James remained in Washington where he opened a workshop making stoves, plumbing fixtures, cookware, and other articles he sold in a business capitalized by $9 thousand in loans from his parents.

Ann Skirving died in 1850. By the end of the 1840s John Skirving was devoting more time to ambitious artistic projects, including coordinating the creation of a monumental moving panorama depicting John C. Fremont’s expedition to Oregon and California.[23] The panorama, begun in 1849 and when finished covered 25,000 square feet of canvas and required two hours to scroll through, was exhibited in Boston and England before disappearing in 1851 following a showing in London’s Egyptian Hall.

After Ann’s death Skirving was back in Washington bidding for federal contracts. While in Washington, he lived with his son James and he worked on various Washington projects, including surveying Lafayette Square in 1851 under Andrew Jackson Downing. Between 1851 and 1852 he worked again on the Patent Office and was Thomas U. Walter’s superintendant in the reconstruction of the Library of Congress after it burned in 1852.

Men of Progress

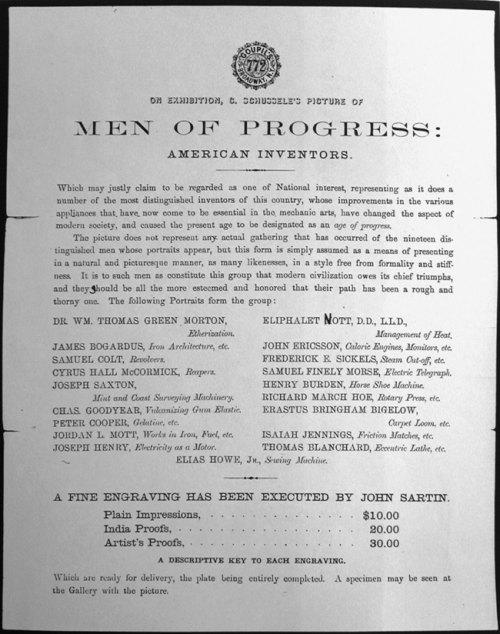

An extended illness began in 1853 and curtailed Skirving’s work. In the mid-1850s he traveled widely seeking relief from his unspecified ailments and he toured European hospitals to view their ventilation systems. When Skirving returned to Philadelphia, he befriended engraver John Sartain (1808-1897) and painter Christian Schussele (1824-1879) and the three began a series of influential collaborations involving historical simulacra painted by Schussele and engraved by Sartain, with Skirving securing the underwriting, sitters, and sales. Skirving bought part of a Germantown, Pennsylvania, estate in the spring of 1859 and later that year convinced his longtime friend Jordan L. Mott to underwrite a project in which Schussele would paint a scene depicting a fictional caucus of seventeen (later expanded to nineteen) of the nation’s best-known living inventors with Sartain producing a mezzotint engraving. The Men of Progress – American Inventors painting showed Samuel Morse (telegraph), Samuel Colt (revolver), Elias Howe (sewing machine), and sixteen others gathered beneath a portrait of Benjamin Franklin in a composition designed to inspire young mechanics and scientists to achieve their greatest potential.

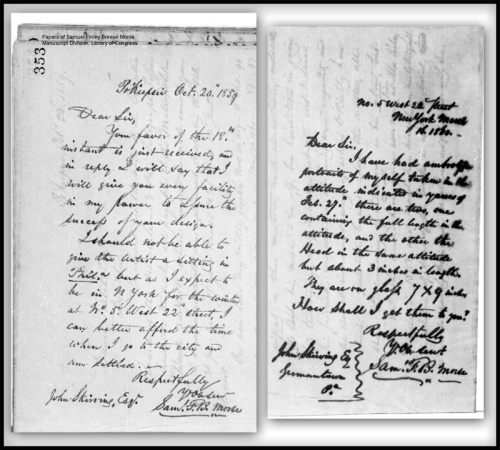

Writing to the inventors depicted in the painting, Skirving put his power to persuade to use in convincing each inventor to visit Schussele’s Philadelphia studio for sittings. Skirving and Schussele’s objective was to create a portrait of each inventor so that they could be arranged as a “form of a convention, or conversazione … a means of presenting in a natural and picturesque manner so many likenesses together, and as free as possible from formality and stiffness.”[24] The negotiations provide a view into Skirving’s bargaining skills. The painting and engraving reflect an aesthetic that captured the nation’s ideals in an age of factories, railroads, and national markets in which scientists were reinvented as heroes. Art and technology historians hail Men of Progress as a turning point in American art and the depiction of scientific innovation in popular culture.[25] Skirving himself anticipated the painting’s significance in an 1859 letter in which he confided to a friend: “It will make one of the most valuable historical paintings ever executed.”[26]

Correspondence from Samuel Morse to John Skirving, 1859 and 1860, on arranging sittings for the Men of Progress painting. Papers of Samuel Finley Breese Morse Manuscript Division, Library of Congress

While working on the Men of Progress project, Skirving’s friend Thomas U. Walter asked him to superintend the construction of Walter’s anticipated retirement home in Germantown near Skirving’s home. Walter relied on Skirving to handle all of the preliminary steps prior to construction of the house, from obtaining a building permit to managing contractors and excavating the cellar. Skirving also was instrumental in designing the landscape (vegetable garden, grape arbors, fruit trees, etc.) in the double lot Walter purchased in the fall of 1860.

Schussele finished the Men of Progress painting in 1862. He painted two versions: a larger one sent to Mott in New York and a smaller one for John Skirving. The painting was hanging in Skirving’s Germantown house when he died there of cancer May 25, 1865. Although the engraving was completed c. 1864, prints from it were not widely made until after Skirving’s estate was settled. The massive steel engraving eventually was sold to Scientific American, which sold prints as a premium for new subscribers.[27] The plate was destroyed in an 1882 fire that engulfed the New York building that housed the Scientific American offices.[28]

Skirving had remarried in 1864, a few months after his oldest son, James, died in Washington. His $20,455 estate was divided among his widow Mary (d. 1903), daughters, surviving son John, and James’s widow, Caroline. Despite his wide-ranging and long career, there were no obituaries written for John Skirving and he quickly faded into historical obscurity. Thomas U. Walter simply wrote in a letter to a friend, “Poor John Skirving has gone to his account, he was not long after his son.”[29]

Skirving worked in the margins during his career, never achieving the recognition of his contemporaries and friends in art and architecture. His importance as the first ventilation expert hired to improve the Capitol’s air and his work on many of Washington’s landmark public and private buildings remains in the shadows cast by Walter, Mills, Strickland, and others. Preservationists looking for Andrew Jackson Downing’s fingerprints in the bricks and mortar of the former Riggs farmhouse have largely overlooked Skirving’s more likely contributions, hinted at by a board with his name painted on it attached to ceiling joists in the cottage’s second story addition and only recently uncovered by the National Trust for Historic Preservation. A little more than a century after he first arrived in Washington, the National Gallery of Art acquired Skirving’s Men of Progress canvas in 1942. After briefly hanging in the White House from 1947 to 1965, the painting moved to the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery and it hangs in a first floor gallery in the former Patent Office Building. John Skirving’s final project had found a home in the architect’s first Washington venture.

Men of Progress hanging in the National Portrait Gallery, Gallery, Washington, DC. Photo by David Rotenstein, 2007.

Notes

[1] Jeffrey A. Cohen, “Building a Discipline: Early Institutional Settings for Architectural Education in Philadelphia, 1804-1890,” The Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 35, no. 2 (June 1994): 139-83; Donna J. Rilling, Making Houses, Crafting Capitalism: Builders in Philadelphia, 1790-1850 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001).

[2] John B. Cutler, “Girard College Architectural Competition 1832-1848” (Ph. D. diss., Yale University, 1969), 75.

[3] National Archives Building, Washington, D.C., Record Group 42, Records of the Office of Public Buildings and Public Parks of the National Capital, Letters received, 1791-1867 (microfilm). Document No. 3028, 4 December 1841, Letter from John Skirving to the Commissioner of Public Buildings.

[4] John Skirving, Ventilation: A Great Preventive of Consumption and Cholera (John Skirving, 1848).

[5] Peter H. Falk and Anna Wells Rutledge, eds., The Annual Exhibition Record of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (Madison, CT: Sound View Press, 1988), 204; George Cuthbert Groce and David H. Wallace, Dictionary of Artists in America, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1957), 583.

[6] Thomas Ustick Walter, Letter to Richard M. Hunt (Washington, 26 April 1860). Smithsonian Institution Archives of American Art, Thomas Ustick Walter Papers, 1829-87, Reel 4140.

[7] Letter from John Skirving to the Commissioner of Public Buildings, 4 December 1841.

[8] David Boswell Reid, Illustrations of the Theory and Practice of Ventilation, (London: Printed for Longman, Brown, Green, & Longmans, 1844), 71.

[9] U.S. Congress. House of Representatives. Committee on Public Buildings, H. Rep. 879, 27 Cong. 2d sess., at 4 (1842).

[10] Douglas E. Evelyn, “A Public Building for a New Democracy: The Patent Office Building in the Nineteenth Century” (Ph. D. diss., George Washington University, 1997), 251; Melissa McLoud, “Craftsmen and Entrepreneurs: Builders in Late Nineteenth-Century Washington, D.C.” (Ph. D. diss., George Washington University, 1988).

[11] Edward J. Balleisen, Navigating Failure: Bankruptcy and Commercial Society in Antebellum America (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001).

[12] John Skirving, Letter to Edward Lyons (Philadelphia, 23 July 1837), Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Society Small Collections – Edward Lyons Papers.

[13] John Skirving, Letter to Edward Lyons (Philadelphia, 1 September 1838), Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Society Small Collections – Edward Lyons Papers.

[14] William Strickland, Letter to Robert Mills, 25 November 1839. Smithsonian Institution National Portrait Gallery Library, The Papers of Robert Mills, 1781-855, Document No. 1969.

[15] John Skirving, Letter to Edward Lyons (Philadelphia, 1 May 1840), Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Society Small Collections – Edward Lyons Papers.

[16] “Presidents and Poor People,” Workingman’s Advocate, August 3, 1844.

[17] William H. Degges, “Specifications of Materials & Workmanship, of a House to Be Built for Geo. W. Riggs on His Farm Near Rock Creek Church, Formerly the Property of M Agg,” 23 July 1842. Library of Congress. Manuscript Division, Riggs family papers, 1763-945, Business Papers, George W. Riggs, Jr., 1836-1852. Container 67.

[18] Degges, “Specifications of Materials & Workmanship, of a House to be Built for Geo. W. Riggs on his Farm near Rock Creek Church, Formerly the property of M Agg.”

[19] Dell Upton, “Pattern Books and Professionalism: Aspects of the Transformation of Domestic Architecture in America, 1800-1860,” Winterthur Portfolio 19, no. 2/3 (Autumn 1984): 107-50. While Downing was an unlikely source of Skirving’s design aesthetic in the early 1840s, pioneering English landscape architect John Claudius Loudon may have been accessible and influential to Skirving.

[20] George Caleb Bingham, Letter to James S. Rollins (Washington, 26 December 1853). Western Historical Manuscript Collection-Columbia, Mo., James S. Rollins Papers, Collection No. 1026, Folder 20.

[21] “Reviews. Architecture,” Review of Hints on Public Architecture, by Robert Dale Owen (Washington, DC: Building Committee of the Smithsonian Institution, 1849), The Literary World 16 June 1849: 510-11.

[22] James Crutchett, Patent Solar Gas and Gas Apparatus, Patented by James Crutchett, of Washington City, for Lighting Cities, Blocks of Buildings, Hotels, Churches, Public Halls, Restaurants, Steamboats, Mills, Factories, and Private Residences (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: North American Book and Job Printing Company, 1847); Robert R. Hershman and Albert W. Atwood, Growing with Washington, the Story of Our First Hundred Years, 1848-1948. Prepared by Robert R. Hershman and Edward T. Stafford. Ed. by Albert W. Atwood (Washington, DC: Washington Gas Light Company, 1948), 21-23. For a discussion of Crutchett’s lantern, see William C. Allen, History of the United States Capitol: A Chronicle of Design, Construction, and Politics (Washington, DC: U.S. GPO, 2001), 178-79.

[23] Joseph Earl Arrington, “Skirving’s Moving Panorama: Colonel Fremont’s Western Expeditions Pictorialized,” Oregon Historical Quarterly 65, no. 2 (1964): 133-72; Thomas Hart Benton, Thrilling Sketch of the Life of Col. J.C. Fremont (United States Army); with an Account of His Expedition to Oregon and California, Across the Rocky Mountains, and Discovery of the Great Gold Mines. (London: J. Field, 1850); Martha Sandweiss, Print the Legend : Photography and the American West (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002), 94-97.

[24] John Skirving, Key to the Engraving of Men of Progress – American Inventors (Germantown, Pennsylvania: John Skirving, n.d.), 1.

[25] Margot Gayle and Carol Gayle, Cast-Iron Architecture in America: The Significance of James Bogardus (New York: W.W. Norton, 1998), 211-12; Brooke Hindle and Steven Lubar, Engines of Change: The American Industrial Revolution, 1790-1860 (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1986), 75-76; Merritt Roe Smith, “Technological Determinism in American Culture,” in Does Technology Drive History? The Dilemma of Technological Determinism, ed. Merritt Roe Smith and Leo Marx (Cambridge, Mass.: The MIT Press, 1994), 1-35.

[26] John Skirving, Letter to Sylvester Wolle (Germantown, 26 December 1859). The Moravian Archives, Records of the Female Seminary, Bethlehem, Pennsylvania.

[27] “Our Splendid Engraving,” Scientific American, January 29, 1870, 78; John Sartain, The Reminiscences of a Very Old Man, 1808-1897 (New York: D. Appleton and company, 1899), 232. Thanks are due to Prof. Howell Harris for finding a flaw in the Men of Progress engraving timeline presented in the 2007 version of this paper.

[28] “Flames in a Death Trap. The Potter Building Completely Destroyed,” The New York Times, February 1, 1882, sec. A; Sartain, The Reminiscences of a Very Old Man, 1808-1897, 232.

[29] Thomas Ustick Walter, Letter to Captain West (2 June 1865). Smithsonian Institution Archives of American Art, Thomas Ustick Walter Papers, 1829-87, Reel 4142.

© 2007-2010 David S. Rotenstein

Shortlink for this post: https://wp.me/s1bnGQ-skirving

This is fascinating, and for me a fabulous find.

I’d seen some of the Skirving drawings in the Historical Society of Philadephia, while trying to find out more about his daughter Elizabeth (she had married the primary subject of my research, Rufus Grider, just before John Skirving died).

Grider was also involved with Sartain and Schuessele, and now my hunch that the connection came through his father in law is more than confirmed. I must get back to work on the biography — meanwhile, I’ve curated a show of Grider’s work in the museum URL’d above.

Can’t wait to delve deeper into your blog, Historian for Hire.