Earlier this month PBS aired Make No Little Plans: Daniel Burnham and the American City. As an architectural historian I have long admired Burnham’s work. Union Station and the Mall are incredible amenities for folks like myself living in the Washington area. My interest in Burnham, however, goes beyond the architectural and city planning spheres. When he married Chicago Union Stockyards president John B. Sherman’s daughter Margaret, Burnham became part of the extended Allerton family, livestock entrepreneurs who profited from the shipment of most of the meat animals shipped into New York City during much of the nineteenth century.

Although Burnham never went into business with his father-in-law beyond his firm’s design of Sherman’s home and the Chicago Union Stockyards landmark gate, he did benefit from Sherman’s Chicago interests and he may have benefited from Sherman’s longtime relationship with the Pennsylvania Railroad. John B. Sherman (1825-1902) and Samuel W. Allerton Jr. (1828-1914) were cousins whose families had been in business together since the first decade of the nineteenth century. My 2002 article, Hudson River Cowboys: The Origins of Modern Livestock Shipping, looks at some of the Allerton family’s business genealogy and my forthcoming article on the East Liberty Stockyards (Western Pennsylvania History, Winter 2010) expands on the Allerton and Sherman firms.

Chicago Union Stockyards entrance designed by Daniel H. Burnham, c. 1875. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

But back to Burnham and to Washington. Burnham in 1901 was hired by the McMillan Commission in its efforts to recreate the federal city envisioned by Peter L’Enfant and remove noisome nuisances like the Pennsylvania Railroad station from the Mall. Prior to the implementation of the McMillan Plan, the National Mall was bisected by railroad tracks and open sewers euphemistically called canals. To achieve the McMillan Plan’s goals towards becoming the City Beautiful, the nuisances had to go. Nearly 40 years after Burnham brought the City Beautiful to Washington, his ideals were deployed by advocates seeking to rid the District of Columbia of the business dominated by Margaret Sherman Burnham’s family.

Before the McMillan Plan and later efforts to sanitize Washington’s gritty urban landscape by clearing out alley dwellings and the wholesale involuntary relocation of entire communities, Washington had a vibrant industrial landscape interspersed with its federal buildings and emerging residential neighborhoods. Lost among the many histories of Washington’s urban fabric are the agricultural industries that thrived within the city. Large working farms, like the Soldier’s Home, raised cattle and vegetables within the city limits. Cattle, hogs, and sheep were driven into the city on turnpikes and concentrated in drove yards like the Drover’s Rest in Georgetown, on the Mall, and on Capitol Hill. The animals driven to Washington’s drove yards were killed in nearby slaughterhouses and sold in the District’s markets.

Beef Depot Monument, 1862. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. Shows cattle grazing at the foot of the unfinished Washington Monument.

Cattle grazing on the U.S. Soldiers' Home farm. Undated photo, National Archives and Records Administration.

When railroads began carrying the bulk of the nation’s meat animals starting in the 1850s, Washington’s drove yards followed patterns laid down in other eastern cities and they relocated adjacent to the railroads leading to the city center. For the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, this meant opening drove yards on Capitol Hill along First Street N.E. between North E and F Streets. Unlike its trunkline competitors, the Pennsylvania, the New York Central, and the Erie railroads, the B&O was a latecomer to the livestock business. Like the other railroads, the B&O outsourced (via valuable contracts) its livestock yarding to professional drovers and livestock entrepreneurs. In Washington, the B&O did business with William E. Clark (1835-1895). Clark was a Pennsylvania native who began managing the B&O drove yards in 1861. Located near the B&O station, the drove yards were little more than impermanent pens where animals were kept before being sold to local butchers; horses and mules that came in on the railroad went to different markets for work in Washington’s streets.

The drove yards remained on Capitol Hill through 1877 when the land adjacent to the B&O’s Capitol Hill tracks was sold and the operation moved up the line and onto the Metropolitan Branch to Queenstown in what is now the Brookland neighborhood. Throughout the 1870s, Clark and several partners tried to get a charter from Congress to incorporate the “National Drove-Yard Company of the District of Columbia”. The company proposed to build a stockyard and market facility complete with pens and scales where all of the District’s livestock business could be concentrated. The 1876 bills to incorporate the business stalled in the Committee on the District of Columbia. For a little more than a decade, the former Queen Farm served as the B&O’s livestock depot in the District of Columbia. Beyond livestock market reports, maps, and a former “Drove Yard lane” mentioned in a 1900 volume on Washington trolley trips, little appears to have survived in the historical record regarding the B&O’s Queenstown Drove Yards.

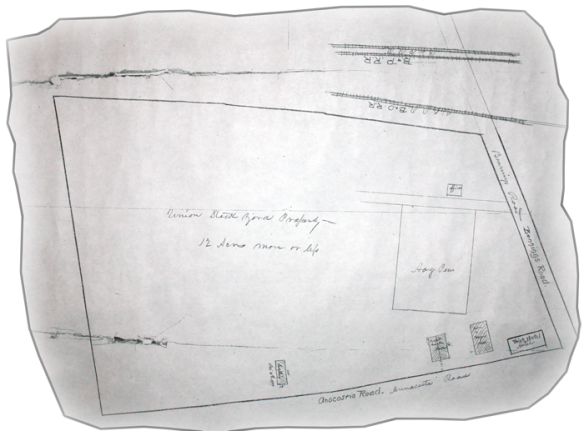

Queenstown Drove Yards mapped shortly after they opened in 1878. Atlas of Fifteen Miles Around Washington Including the County of Prince George Maryland, Plate 83.

Since the arrival of the B&O into Washington, the District of Columbia had close ties to Baltimore’s livestock and meat-producing industry.With two railroads in the city, the Pennsylvania and the B&O, Baltimore developed two railroad drove yards. The Pennsylvania’s was adjacent to that road’s Baltimore & Potomac Railroad at Calverton Station west of the city. The Calverton Drove Yards were first managed by livestock entrepreneur Cary McClelland who had bought up much of the land near the station; later, the yards were run by the Calverton Stock Yards Company. The B&O’s drove yards were located at the railroad’s main yards at Mount Clare until 1880 and the incorporation of the Baltimore Stock Yard Company of Baltimore County when the yards were shifted west to Claremont. (In 1891, the two companies merged to form the Union Stock Yard Company of Baltimore County and Claremont became Baltimore’s principal stockyards.) By the early 1880s, Alvin N. Bastable (1837-1922), a Virgina native had begun concentrating all of Baltimore’s livestock business. In 1887, Bastable along with Philadelphia stockyards owner and meatpacker Joseph Martin (Samuel Allerton’s partner in the Philadelphia and Jersey City Stockyards and an owner of the Baltimore Union Stock Yards) and Clark, received a corporate charter from the State of New Jersey for the “Union Stock Yard Company” to build and run a fully integrated stockyards and slaughterhouse business in the District of Columbia. One year later, the Union Stockyards opened next to the B&O and Pennsylvania Railroad tracks south of Benning Road on the east side of the Anacostia River. The new stockyards served both roads. Shortly before they opened, the Pennsylvania Railroad issued these instructions to its freight agents:

General Notice. Hereafter, all shipments of Live Stock For Washington D.C., will be handled at Union Stock Yards, located at Benning’s Station, on Baltimore & Potomac Railroad. Agents will forward all shipments of Live Stock destined to Washington D. C. to “Union Stock Yards, Bennings Station, Md.”

Four months later, the railroad updated the earlier notice:

Here’s the notice that supercedes that notice! All Live Stock, in car loads,(except horses), destined to Wash D.C. ,will hereafter be receipted for & forwarded to Union Stock Yards. Shipments of horses, in car loads or less, & all other live stock, in less than car loads, will be receipted for & forwarded to Wash. D.C. , unless shippers request delivery at Union Stock Yards, in which case shipments should be sent to Union Stock Yards, Wash D.C.Philadelphia.

Over the next four decades the abattoir and stockyards at Benning Station were the District of Columbia’s livestock depot and market as well as the District’s principal slaughtering facility. Bastable, along with long-established Washington butchers, created several corporations under which several slaughterhouses operated next to the stockyards at the Benning Road and Minnesota Avenue intersection. By the 1920s, trucks began to supplement the rail deliveries of cattle. Farmers from Prince George’s County and other parts of Maryland delivered their animals at the stockyards for sale and slaughter. Benning Station was Washington’s version — on a much smaller scale — of Chicago’s stockyards and Packingtown.

1907 Washington Post advertisement run in the wake of federal investigations done after the publication of Upton Sinclair's The Jungle.

According to various sources, as much as 75 percent of the dressed meat produced in the District of Columbia originated in the Benning stockyards and slaughterhouses. Before closing, the Benning Station yards handled between 10 and 20 thousand cattle (excluding calves) annually. Hogs during the same period ranged from c. 50 thousand annually to 190 thousand (in 1924 and 1928). In addition to providing the District of Columbia with much of its meat supply, the stockyards and abattoir provided jobs to the men and women living in the adjacent working class neighborhoods of Northeast Washington.

A fire in 1934 swept through the slaughterhouse and subsequent efforts to rebuild it touched off a battle in Congress to outlaw all slaughterhouses, stockyards, and other nuisance industries in the District of Columbia.

T.T. Keane Co. meat delivery truck in Washington. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

Officially known as “A Bill to prohibit the use of buildings or premises in the District of Columbia for the carrying on of certain undesirable industries” and dubbed the “Abattoir Bill,” Congress held hearings in 1937. If enacted, the law would have banned the manufacture of chemicals (fireworks, gas, glue, and acids), rendering, refining, stockyards, slaughterhouses, and tanneries. Parties as diverse as the American Planning and Civic Association, the American Institute of Architects, the Department of the Interior, and various District community organizations all offered testimony supporting the bill while the meat and livestock industry vigorously opposed the bill.The City Beautiful concept first introduced to Washington by Burnham was front and center in the Abattoir Bill hearings, as suggested by Sen. Patrick McCarren (D-Nev.), chairman of the Committee on the District of Columbia subcommittee:

Washington being the Capital City should be the city beautiful and therefore nothing of this nature, that is heavy industries, industries that have a certain unpleasantness with them, should be permitted to exist within the city.

While most of the testimony received in 1937 opposed the abattoir and supported the bill, a few local residents sided with representatives from the meatpacking and other industries targeted in the bill. Northeast Washington resident Charles F. Longus, who lived “within two squares of the abattoir,” wrote a letter to the Washington Star and a typed copy was included in the evidence reviewed during the 1937 hearings. “I am at a loss to know why this has caused such a stir,” he wrote.

As a life-long resident of this place, I think I voice the sentiment of its citizens in saying that during the life of the abattoir it has served the community well. For over 40 years … the abattoir has been the main place of employment, and I believe the life of every resident of Benning has been touched in some way by the operation of the abattoir. It was formerly run by Kane [sic; it was Keane & Co.], Loeffler and Auth and has employed all along from 50 to 100 men regularly, to say nothing of the part-time employees… I think the residents of Benning should have a say in the matter and I think they will say if opening the abattoir means work, by all means open it.

The Benning Citizens Association also opposed the bill. Identifying themselves as “an organized group of tax payers” who “directly represent a very small majority who would be employed” in the abattoir, they asked the subcommittee members, “As to the nuisance of this abbatoir [sic.], we as residents for years in this area wonder where and when the odors were so great that they carried to the Capitol, as said odors did not orriginate [sic.] in Benning.”

After the Abattoir Bill hearings, the District of Columbia revised its zoning law and the slaughterhouse was not rebuilt. Among the principal complaints filed by the federal government was the claim that the stockyards and slaughterhouse imperiled new investments in parkland along the Anacostia and planned public housing projects including Langston Terrace to the west.

Map prepared by the Public Housing Administration showing prevailing wind patterns, the stockyards and abattoir site, and proposed developments.

The stockyards business was hemorrhaging money without a slaughterhouse and local market for meat animals. Its operation after the fire and subsequent legal challenges was limited to resting and watering livestock in long-haul trains. In 1940, the House of Representatives held hearings on a bill to acquire the stockyards and slaughterhouse properties. The bill died in committee and within a year the stockyards property was sold. In 1942 the Union Stock Yard Company was dissolved.

The McMillan Plan changed Washington’s landscape with the implementation of Burnham’s City Beautiful ideal. Throughout the twentieth century, efforts like the 1937 Abattoir Bill sought to fully sanitize Washington’s urban fabric. This cleansing, it appears, extends to the historical record. Recent histories of Northeast Washington’s Brookland and Deanwood neighborhoods fail to mention the once lively, albeit malodorous, livestock and meat-producing industries that once thrived in those neighborhoods and along their margins. For Washington’s historical record to be complete, historians must embrace the city’s unpleasant offal — like the city’s nuisance industries — and incorporate it into the rich neighborhood histories being written for academic and popular audiences.

© 2010 David S. Rotenstein. This post is derived from a work in progress on eastern urban stockyards.

Shortlink for this post: https://wp.me/p1bnGQ-er

The industrial side of Washington is under-explored and under-documented.

Most histories of Georgetown don’t emphasize its industrial and malodorous past, either, so let’s not be too hard on our colleagues.

Note that a lot of this information might be found in the vertical files in Washingtoniana Division under

AbbatoirAbattoir (the first file in the cabinets).Excellent post! As an architectural historian buff though, I thought I should clear up an often mistaken assumption of the work of Burnham and Root. Root was the designer up till his death in 1890, after which the Buisnessman/Manager Burnham hired another series of designers over the years. The Union Stockyards where designed by the firm of Burnham and Root, but by the architect John Wellborn Root.

Thank you for the excellent post about the smelly underbelly typical of many cities. Would have enjoyed hearing more about the Thanksgiving dinner conversations between the Burnham and Sherman families!

Very interesting site. I am interested in gathering some historical information on John B Sherman’s summer home in Michigan (as I am told). As far as I understand he had a residence in Mount Clemens Michigan and I am the current owner and am looking on restoring this home to its original grandeur. Any suggests as to where to look? I would be very grateful for any photos at all.

Thanks to any suggestions at all. I just feel that it would be a shame to see this home in disrepair.

Chris, you could try the Chicago Historical Society.

I would like to have information on the history of Union Stock Yards in Baltimore Md’. of which my Great -Uncle was President , during 1940s – early 1950s.Not sure of date.

Thank you for any help