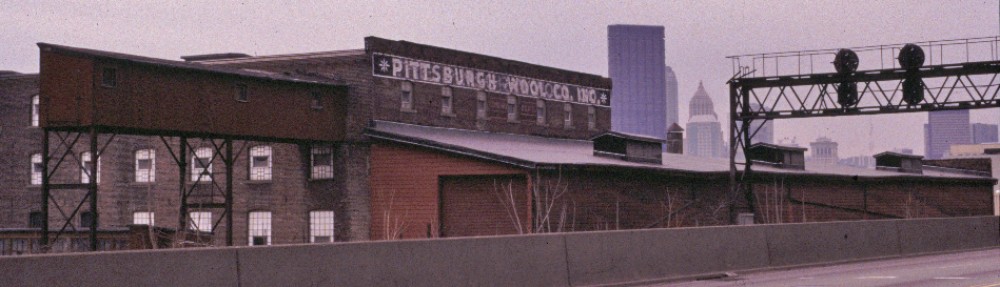

Ninth Street Bridge, Spanning Allegheny River at Ninth Street, Pittsburgh, Allegheny County, PA. HAER photo by Jet Lowe.

In 1897, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers fired the first shot in a war with Pittsburgh, Pa., bridge owners, industrialists, and the local government. Industrialists like H.C. Frick and riverboat interests told the federal agency that Pittsburgh’s bridges were too low and that they obstructed navigation.

Two years later, acting on information provided by the Corps of Engineers, Congress passed a law authorizing the Secretary of War “to notify the owners of bridges and other structures” that their structures were obstructing navigation. The new law also gave the federal government the power to force bridge owners to make corrections at their own expense.

The Union Bridge spanning the Allegheny River and connecting downtown Pittsburgh and Allegheny City (not Pittsburgh’s Northside neighborhood) was the War Department’s first target. In 1902, the Department wrote to the Union Bridge Company with orders to mitigate the bridge’s impacts on river navigation.

The Union Bridge company was instructed to raise its bridge. The company countered that the order would create an undue financial hardship and sued. The government won and the case was appealed. Ultimately, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the lower court’s ruling and the Union Bridge was replaced (204 U.S. 364).

As the Union Bridge case worked its way through the courts, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers put Captain William L. Sibert, the Pittsburgh District’s chief engineer, in charge of improving river navigation through the city. In March, 1903, Sibert submitted a report to Secretary of War Elihu Root recommending that the bridges spanning the Allegheny river be raised.

Root declined implement Sibert’s recommendations and so did his successor, William Howard Taft. Taft believed that the bridge issue was best left to the local authorities.

As the War Department struggled with conflicting mandates — keeping the rivers navigable and obeying orders from civilian authorities — other battle lines involving Pittsburgh’s bridges emerged. The city’s bridges were privately owned and the companies were funded through tolls collected at the bridge portals. In 1910, Allegheny County commissioners began evaluating buying or condemning the bridges to eliminate the tolls.

The following year, the county bought five of the six Allegheny River bridges. The owners of the Forty-Third Street Bridge refused to sell. Signs quickly went up at the Sixth, Seventh, Ninth, Sixteenth and Thirtieth streets bridges: “This bridge, by an act of the County of Allegheny, has this day been made free to ordinary public foot and passenger travel.”

The 40th Street Bridge (Washington Crossing Bridge) replaced the 43rd Street Bridge and was completed in 1924. HAER photo by Joseph Elliot. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

Eliminating the tolls didn’t abate the navigation hazards. Finally, in 1917, Secretary of War Newton D. Baker ordered Allegheny County to raise the Allegheny River bridges. By then, the bridge issue was entering its third decade. It took another decade for all of the bridges to be replaced.

Beyond the Page

In 1997, the Historic American Engineering Record (HAER) documented several Pittsburgh bridges in the Pennsylvania Bridges Recording Project. National Park Service historians, architects, engineers, and photographers documented the Sixth, Seventh & Ninth Streets (“Three Sisters Bridges“) and the Forty-Third Street Bridge (“Washington Crossing Bridge“). The photos, drawings, and reports are archived at the Library of Congress. Read more about the Pittsburgh bridge war in the reports.

© 2015 D.S. Rotenstein

Shortlink for this post: https://wp.me/p1bnGQ-2HN