I met the former owner of 526 McKoy Street in Decatur, Georgia, on a cool winter morning the second week of January 2012. She was one of the first interviews I did with Decatur homeowners in the city’s gentrifying Oakhurst neighborhood. Earlier this year, she died at age 86.

526 McKoy Street, Decatur, Ga. May 2015.

I had gone to her home to meet another Decatur resident, one of the city’s original urban homesteaders [PDF]. A longtime friend of the woman’s, he suggested her dining room would be a quiet and convenient place to speak. Soon after the former urban homesteader and I began speaking, the woman started adding to the conversation and I asked her to identify herself for the recording.

“Lillie Mae Wynn. I’m eighty-three.”

Wynn’s family moved to Decatur from nearby Scottdale when she was 18 or 19. Her family lived in the “Old Ps”: local shorthand for “old projects,” the Allen Wilson Terrace public housing complex completed in 1941 and demolished between 2010 and 2014. Her mother could recall the creek that ran through the area called “The Bottom” where 200 apartments replaced African American homes, businesses, and churches under the auspices of slum removal.

“Across from the projects, all that was black,” said Wynn of the downtown African American community once known as “Beacon.” She then said, “And then they came in and they started tearing up – the black people had to move.”

Pages from the 1960s urban renewal pamphlet, “Decatur Fights Decay.”

Wynn bought the McKoy Street home in 1966. She paid $10 down and agreed to assume the payments remaining on the previous owner’s $10,900 mortgage — secured just two years earlier when Joseph Faircloth bought the property from its first owner, Ray Garmon.

Like other Atlanta area African Americans, Wynn couldn’t get a mortgage from a local bank. Decatur Federal Savings and Loan — the city’s official bank — was notorious for redlining and discriminatory lending well into the 1980s.

“You couldn’t get a loan – I don’t think you, being black, you couldn’t get a loan from Decatur Federal,” said Paul R., the man I had gone to Wynn’s home to meet, “Decatur Federal did a lot of redlining. A lot of it. And I’ve never cared for Decatur Federal. Never.”

Wynn agreed. To get her own mortgage, Wynn had to rely on her daughter’s connections. “You had to join the credit union, somebody would have to work for a government,” Wynn said. “I got into a credit union because my daughter worked for IRS for a year.”

Two days after she closed on the McKoy Street home in July 1966, Wynn got a $1,700 loan from Renee, Inc.

Wynn was the first African American homeowner on her stretch of McKoy Street. Within a week of her arrival, “For Sale” signs sprouted the length of her block. “We just saw the signs and they were gone,” she recalled. The white residents left, selling their homes to African Americans. Ten years later, Wynn told a newspaper reporter that the street was “all black.”

The white residents who were leaving began whispering, “They [African Americans] done moved in,” said Wynn. The whispers were based on racial stereotypes honed under decades of life under Jim Crow: “They always felt like black people always couldn’t keep up property and all that,” explained Wynn.

McKoy Street was one of several streets rapidly altered by white flight. By November of 1966, the Decatur City Commission joined other cities throughout the nation struggling to stanch the flow of whites into the suburbs and it enacted a law prohibiting “For Sale” signs in residential yards.

Seemingly overnight, South Decatur — today’s Oakhurst — went from an all-white neighborhood to a majority African American one. By 1970, the neighborhood and its schools were predominantly African American and increasingly poor. Once a stable (and segregated) working-class neighborhood, South Decatur’s new majority population were mainly displaced people from urban renewal areas in Decatur and neighboring Atlanta. They also were former public housing residents taking advantage of new housing opportunities opened up by civil rights cases won in the federal courts and federal legislation.

Abandoned home sold in Decatur’s urban homesteading program, before and after rehabilitation. Undated photos courtesy of the Decatur Housing Authority.

By the mid-1970s, more than a tenth of South Decatur’s homes were abandoned and in foreclosure. The neighborhood’s businesses — notably, the Colonial Foods grocery store and the Scottish Rite Hospital for Crippled Children — followed the white residents out of Decatur leaving behind a blighted crossroads in South Decatur’s core.

New Colonial store under construction, c.1964. Courtesy City of Decatur.

Like many of her neighbors, Wynn remained in South Decatur through its down years. In the mid-1970s, Decatur briefly tried to turn the neighborhood around through an urban homesteading program and low-interest rehabilitation loans and technical assistance to homeowners like Wynn.

Undated newspaper clipping in private collection, Decatur, Ga.

The Decatur Housing Authority tapped into programs administered by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development to rehabilitate South Decatur. Between 1976 and 1982, the city sold 113 homes for $1 each to urban homesteaders as the smallest city among 23 Urban Homesteading Demonstration Program cities.

Urban homesteading was intended to return vacant homes to private ownership and to municipal tax rolls. The housing rehabilitation programs were meant to reverse architectural deterioration that could lead to abandonment.

According to former Decatur Housing Authority executive director Paul Pierce, the agency had a “two-pronged” approach: “We just didn’t need to get people in these homes while everything else was deteriorating,” Pierce recalled in 2011. “So we created a local loan program … We leveraged some of the funds that we had to create this large pool of rehab funds and so we lent that money at five, five-and-a-half percent.”

Cover of a 1979 Decatur Housing Authority report.

The rehabilitation work done to Wynn’s home was done through the city’s rehabilitation program. In 1977 Wynn received a $17,000 loan from H.U.D. (the deed was prepared by a Decatur Housing Authority official) and two years later she received another $1,700 Housing Authority loan.

The investments that the City of Decatur made in South Decatur and its residents like Lillie Mae Wynn were short-lived. In its efforts a decade earlier to, as the New York Times described it, prevent the city from turning all-African American, Decatur fought to have Atlanta’s new rail line, MARTA, run through downtown instead of south of the central business district in existing rail right-of-way.

Undated MARTA construction photo showing downtown Decatur. Credit: AJCP229-016t, Atlanta Journal-Constitution Photographic Archives. Special Collections and Archives, Georgia State University Library.

The cut-and-cover subway construction decimated downtown Decatur and in 1982, in a desperate move to survive, the city abandoned much of its housing and commercial rehabilitation efforts in South Decatur (rebranded Oakhurst in 1979) and turned all of its attention to downtown redevelopment. Urban homesteading ended and the rehabilitation program shrank. Of course political events outside Decatur, like the election of Ronald Reagan as president in 1980 didn’t help local governments like Decatur that depended on substantial federal support for affordable housing programs.

While the city was focusing on her neighborhood, Wynn was hopeful that better times were on the horizon. “People seem to be keeping (their homes) up more,” Wynn told reporter Emma Edmunds.

But better times didn’t arrive until two decades later. Oakhurst continued its slide into poverty and municipal benign neglect. The crack cocaine epidemic turned Oakhurst’s streets into open-air drug markets. Homes were convenient targets for criminals looking for quick money. Crimes against people and property skyrocketed. Improvements came slowly and with them, new people and new money: young white people, real estate speculators, and risk takers willing to open stores and restaurants in the business district.

By the turn of the 21st century, Oakhurst was a transforming place and Wynn welcomed many of the changes.

“It is nice, quiet,” Wynn said of her street now. “It’s more whites now and there are about three blacks.” The corner drug dealers are gone and the houses are a lot nicer. Except for losing her neighbors to displacement and death, Wynn was happy with the direction her neighborhood went after 2000.

Unlike the white folks who fled in 1966 who wouldn’t talk to Wynn and other African Americans, the new residents are nicer, yet still different: “But there’s a lot of whites, they’ve bought all the houses down that way … the whites with the children, babies.”

I never saw Wynn again after that January morning. In my interview database she’s number 16 out of 94 interviews that I did for my book project on gentrification in her neighborhood. She was one of the many friendly people I met during my research there and I wish I could have gotten around to visiting with her again before she died February 27, 2015.

One month before Wynn died, real estate sites were advertising the sale of her home. Zillow.com initially described her home as a “Bungalow in sought after City of Decatur.” The January 2015 ad continued, “Walk to everything! Corner lot available in the area of upscale homes. Great neighborhood! Get in while you can!”

Within a couple of months, the real estate sites changed their copy: “This is a tear down/fixer upper property on a premium corner lot in the heart of Decatur,” read the Zillow ad (captured June 3, 2015).

A Woodstock, Ga., resident bought the property in May 2015. A neighbor who lives on a nearby street told me later that month that there had been a bidding fight over the house. He was sure that the small 1,000-square foot home would end up in a landfill and a substantially larger new home would be built at the site.

Instead, it appears that the small home built in 1952 where Wynn spent more than half her life will get a new chapter — if plans approved in a June 2015 Decatur Board of Zoning Appeals hearing are realized.

As for Lillie Mae Wynn’s story, it gets to live on because of a pair of accidents: a reporter writing about housing rehabilitation in the 1970s and a friend’s 2012 invitation for me to interview him at her dining room table.

Ms. Wynn’s former homesite, August 2016.

© 2015 D.S. Rotenstein

Shortlink for this post: https://wp.me/p1bnGQ-2Ov

My condolences to Ms. Wynn’s family. I never met her, but I wish I had.

At least, however, some physical evidence of her life will remain if her home is not slated for demolition, the fate of so many other smaller Oakhurst homes.

A question…how does the house’s fate relate to the June 2015 Decatur Board of Zoning Appeals decision mentioned here?

Great post. Thanks.

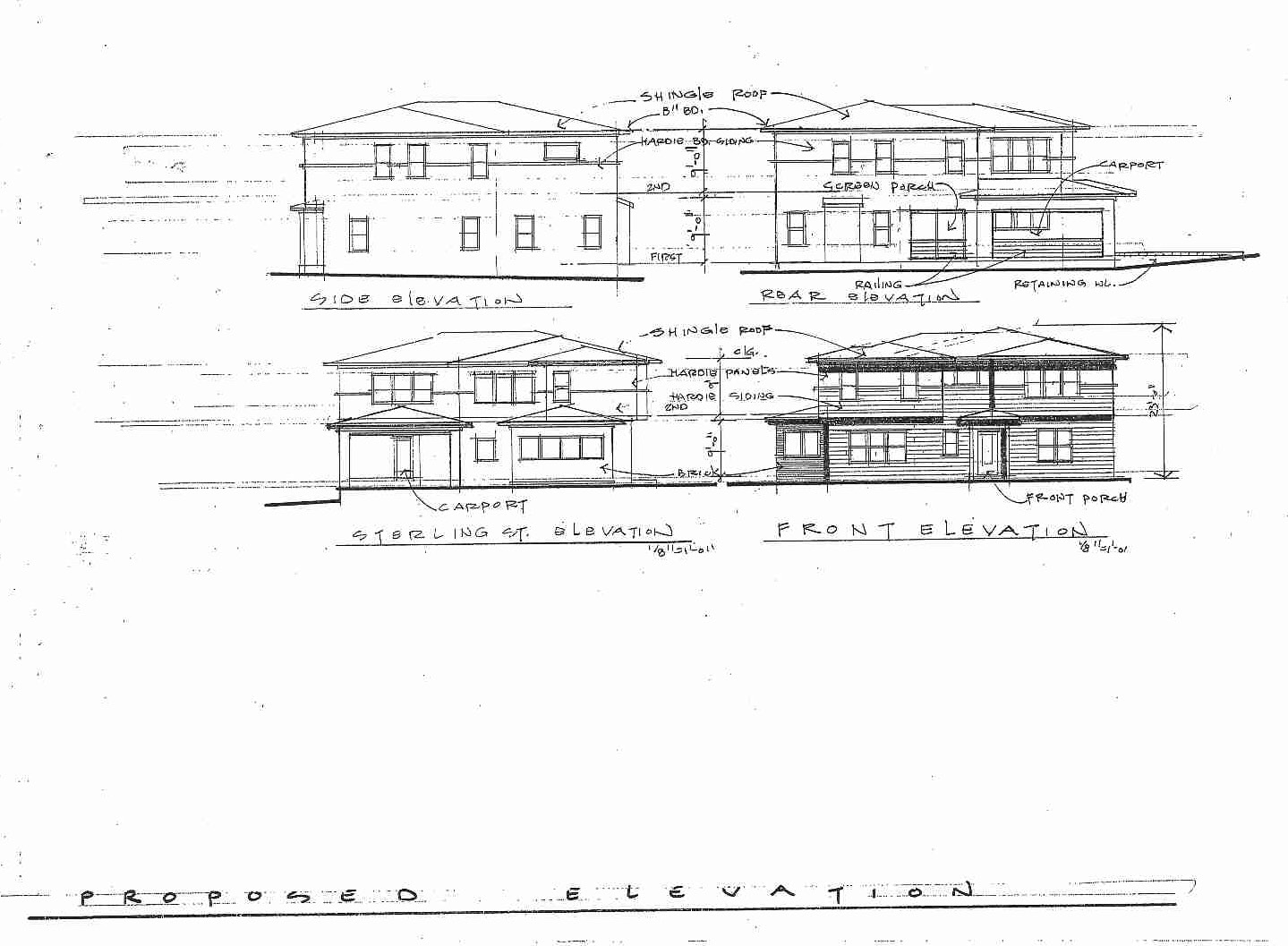

Ann, the June 2015 proposal includes constructing additions (second story, rear). Based on drawings provided to the BZA, the new work will render the older home larger and unrecognizable by enveloping its original massing. There are worse examples — and better ones — in Oakhurst; the June 2015 proposal falls somewhere in-between. It still qualifies as mansionization, will contribute to the upward spiral of property values and property taxes, and likely will spur additional teardowns in the block (there’s substantial evidence that teardowns are contagious) further propelling the neighborhood towards economic, racial, age, and architectural homogeneity.

Here’s the rendering submitted to the BZA for its June 8, 2015 meeting.

Ms. Wynn is a name I remember. I grew up in The Old Ps and she never forgot us. Ms Wynn and a select few others kept order among the kids and organized relief for the adults when possible. She was a highly respected legend of my childhood.it saddens me to read of her passing. I was honored to learn more about Ms Wynn’s pioneering spirit.