Introduction

Moses Order logo, c. 1887.

I first “met” Henry White in 2017 while researching a suburban Washington, D.C., cemetery. White was a founder and the namesake of White’s Tabernacle No. 39 of the Ancient United Order of Sons and Daughters, Brothers and Sisters of Moses. Henry (sometimes called “Harry” in historical records) was born c. 1847 in North Carolina. By the late 1870s, he was married and living in an African American hamlet in the District of Columbia established by free Blacks in the 1830s.

Henry White and his wife, Clara, had several children during their marriage. After Henry died, one of their children moved to Allegheny City, Pennsylvania. Henry White left no diaries or photographs and he died intestate. His traces in the historical record are slim, but compelling. While searching for information that would help me to understand Henry White and his time in Washington, I found a 1930s legal case in which his kin were named as defendants in litigation brought to clear the title to properties in the former hamlet where Henry and Clara raised their children. Among the briefs and depositions were papers filed by William Miles White, a resident of Allegheny County, Pennsylvania. He was the same “Miles White” who was just a few months old in June of 1870 when a census enumerator visited Henry and Clara White’s rented Tenallytown (Tenleytown) home.

I finished the cemetery research and its results were presented in a report submitted to the descendants of the people associated with the White’s Tabernacle cemetery and agencies in Montgomery County, Maryland, and Washington, D.C. William Miles White and his life in Pennsylvania became an open question to follow up on later. Later arrived in 2019 when we moved back to Pittsburgh.

Like his parents, Miles White left few traces in the historical record. But also like his father, what evidence he did leave raises some intriguing questions about where he lived and how he fit into complicated racialized urban and suburban landscapes. This post is a step towards answering those questions.

Family Ties

Henry White (c. 1847-1895) is invisible in the historical record before 1870. That year, a census enumerator visited his rented home in the District of Columbia’s Tenallytown community. Tenallytown, also known as Reno City, was a Reconstruction-era suburb with a large number of African American residents, many of them property owners. Clara Brown White (born c. 1850) was a Maryland native. Their nearby neighbors, according to the U.S. Census, were John and Eliza Hepburn, William Botts, Marshall Frazier, and the Davis family, all African Americans.

Like many African Americans of the period, the Whites left few documentary traces. Census schedules simply identified him as a “laborer,” yet he was able to accumulate sufficient capital to buy land and he held a leadership position in a prominent benevolent organization. There is some evidence that White’s wife’s maiden name might have been Brown, a relative (sister?) of another White’s Tabernacle founder, Charles H. Brown.

Legal case envelope, c. 1870s.

White’s Tabernacle was a Washington subordinate satellite of the Ancient United Order of Sons and Daughters, Brothers and Sisters of Moses (Moses Order). Founded in 1867 by a Philadelphia physician and Republican party leader, the order was one of many similar charitable organizations, oftentimes called secret societies, that became integral institutions in African American communities. These organizations first appeared in the United States before the Civil War as free Blacks established Prince Hall Masons and Grand United Order of Odd Fellows lodges. After the Civil War, these organizations and others spread from northern cities into the South giving African Americans agency and ownership over their own institutions. Black benevolent organizations provided African Americans a safety net and economic security. They provided burial and health insurance and were vehicles for accumulating wealth and social capital.

By the mid 1870s, the Moses Order had spread to other Mid-Atlantic states, including Maryland and the District of Columbia. The organization that came to be known as White’s Tabernacle No. 39 was founded in Washington in 1870; it was one of several tabernacles founded in Washington between c. 1870 and 1900.

Henry White was a founding member of a Moses Order tabernacle that split from the original 1870 group in the mid-1870s. They all appear to have lived in Reno/Tenallytown and the Broad Branch Road-Rock Creek Ford Road area in Northwest Washington. They all were property owners in a tract consolidated between the 1830s and the 1850s by free Black brothers John and Thomas Hepburn. By the time that the Civil War started, their 8-acre parcel, inscribed with their family name, is visible in Washington real estate maps published in the late 1850s and early 1860s.

Hepburn tract, c. 1857. Boschke, A. “Map of Washington City, District of Columbia, Seat of the Federal Government: Respectfully Dedicated to the Senate and the House of Representatives of the United States of North America.” Washington: A. Boschke, 1857.

John Hepburn died in 1872. His widow had the tract surveyed the following year and she began selling parcels to African American buyers. The half-acre parcel that Henry White bought originally was sold in 1873 to Robert Dorsey, a sexton and Moses Order founder. Four years later, Dorsey sold the parcel to Henry White. Ultimately, by the 1890s Hepburn’s tract had been divided into fourteen properties: thirteen homesites and one cemetery, all Black owned. Testimony by people who rented property in the tract during the early twentieth century revealed that the space was not named. An attorney for the landowner in the 1930s asked Edward H. Boose, a white man who had moved to 5632 Rock Creek Ford Road in 1903, if he knew the place by any particular name. “No sir, other than Rock Creek Ford Road,” Boose answered.

Henry White’s property and the former Hepburn tract, Washington, D.C., c. 1881. Carpenter, B. D. “Map of the Real Estate in the County of Washington, D.C. Outside of the Cities of Washington and Georgetown: From Actual Surveys.” Washington, D.C.? B.D. Carpenter, 1881.

Washington attorney and real estate investor William Walton Edwards acquired all of the former Hepburn tracts between 1899 and 1920; he rented them out to tenants. Several parcels had been seized by the District of Columbia for delinquent taxes. Edwards died in 1927 and his family spent five years clearing the title to his Rock Creek Ford Road property to settle his estate.

Edwards v. White case envelope.

The Edwards family litigation is what led me from Washington to Pittsburgh.

Kin and Community on Pittsburgh’s North Side

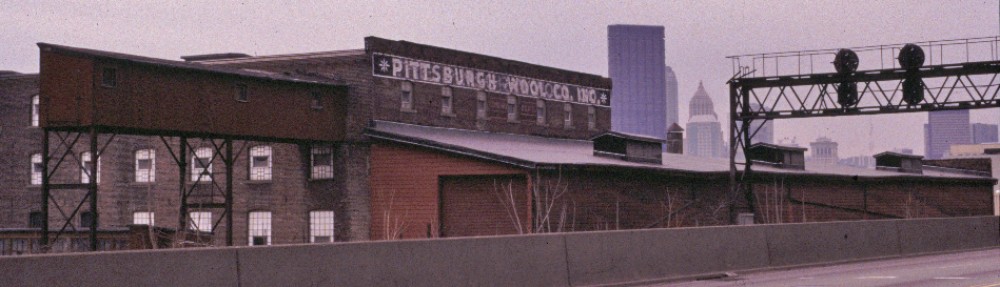

Miles White moved to Allegheny City, where he lived for about 30 years until his death. Allegheny City was Pittsburgh’s sister city across the Allegheny River. Like Pittsburgh, Allegheny had a rich industrial and ethnic history before the larger city annexed Allegheny in 1907. Ever since the annexation, Allegheny City’s neighborhoods collectively have been known as Pittsburgh’s “North Side.”

White’s first known stop in Allegheny was a small frame house he and Ella rented which was located in the city’s Second Ward in a crowded street called Lane Alley. According to the 1900 U.S. Census, Lane Alley had 25 households: 10 Black and 15 white. Miles and Ella lived at No. 32 and he was identified as a teamster; Ella did “washing and ironing.” Their African American neighbors, all renters, included other teamsters, a barber, and several women who, like Ella, did domestic work. Whites living in Lane Alley also worked as teamsters and barbering. They also worked as brickmasons and general laborers; there also was a machinist, a wire worker, and a house painter among the renters and boarders living there.

Historians have recognized Allegheny City collectively and individual Pittsburgh neighborhoods as places where African Americans moved before and during the Great Migration. Like their European immigrant counterparts, these immigrants from the American South established their own neighborhoods. Pittsburgh’s early Black neighborhoods reflected racial segregation and Jim Crow’s stranglehold in the Appalachian city about 70 miles north of the Mason-Dixon Line. They also represented African American resilience and the rich cultural capital necessary to create Black spaces teeming with entrepreneurs, traditions, and cultural institutions.

Lane Alley and the location of No. 32 indicated, c. 1901. Source: Hopkins Real Estate Atlas.

The Whites might have seen ads for the property at 32 Lane Alley published in the Pittsburgh Press or they could have learned about available housing by word of mouth. By January 1897, a woman living at 32 Lane Alley was advertising in the Pittsburgh Press to do “washing and ironing or any kind of work by the day.” Ella could have placed these ads — they are similar to ones she bought more than 20 years later using her name.

Advertisement, The Pittsburgh Press, January 15, 1897.

After 1900, for the next 18 years Ella and Miles appear to be invisible in the surviving historical record. They were not counted in the 1910 census — their [presumed] home at 32 Lane Alley had several renters living there — and they transacted no business with government agencies that would have left durable records. They next appear in Allegheny County records in 1918 when they bought a piece of property near Pittsburgh’s northern city limits.

Lane Alley, September 2019. The White home would have been located to the left of the roadway.

In December 1918, Miles and Ella bought property in a subdivision laid out in 1901 by Allegheny City real estate speculator John W. Fester. Fester had carved out 140 building lots and dedicated several streets and alleys in what he called “Richard Place.” The Whites bought Lot No. 50, a rectangular plot on a steep hillside, 25 by 100 feet. Their property included a three-room wood-frame house. They paid using a $1,300 mortgage with 6% interest.

James Fester’s plan showing the original White lot (yellow) and their second lot (red). Source: Allegheny County land records.

The Whites were the second Black family to live at what became 50 Dalton Street. The first family, Alexander and Katie Rucker, had bought the property in 1906. Alexander Rucker was a 43-year-old Georgia native identified as a landscape gardener in the 1910 census. Katie Rucker was 29 years old and identified as a “laundress.” Alexander died in 1912 and Katie acquired title to the property.

Katie Rucker subsequently married Oscar Hill, a Washington County, Pennsylvania, junkyard owner. The Hills sold the Dalton Street property to real estate entrepreneur Gregg L. Neel in 1916. Two years later, Neel sold 50 Dalton Street to the Whites, who appear to have already been living there and renting the home.

White Dalton Street homesite, c. 1925. Source: Hopkins Real Estate Atlas.

Ella continued working as a laundress and seamstress while living at 50 Dalton Street. She also continued taking out advertisements for her services in the Pittsburgh Press. In September 1916, Ella advertised that she as looking for work with a private family as a chambermaid and seamstress.

Pittsburgh Press ad placed by Ella White, September 1, 1916.

Former William and Ella White homesite. The cars are parked in its approximate location. The unnamed alley and Pittsburgh city steps are in the foreground. Photographed September 2019.

View down city steps next to the White’s former Dalton Street property, September 2019.

In the 1920s, Miles and Ella bought additional real estate, including a lot in Pittsburgh’s Lawrenceville neighborhood (across the Allegheny River from the North Side) and the lot immediately adjacent to their home. They paid $300 cash to Butler Seabrune for the lot next to an unnamed alley where the City of Pittsburgh built some of its iconic “city steps” to compensate for the steep grade in the public right-of-way.

Metropolitan Baptist Church, Pittsburgh, September 2019.

Miles died intestate in 1927. His Pittsburgh Press obituary indicated that he was a member of the Sheba Lodge, an Allegheny City masonic order and that his funeral would be held at Metropolitan Baptist Church, the oldest African American Baptist Church in Pittsburgh’s North Side (founded 1850). Ella subsequently advertised for someone to rent a three-room house (with a bathroom) at the property for $20. It is unclear whether the advertisement was for the home she had shared with Miles or if it was a house previously occupied by Seabrune, who had bought his lot in 1919.

September 3, 1927, Pittsburgh Press ad for home to rent at 50 Dalton Street.

Ella died a year after Miles. They both were buried in Pittsburgh’s Uniondale Cemetery; their graves are unmarked, according to cemetery records. Unlike Miles, Ella left a will and her estate was inventoried. Ella White’s probate records provide the most fine-grained view into the family’s life available. They also identified several relatives who lived nearby, including one of Miles’s younger brothers, James, who also lived in the North Side in Jackson Street and Margaret Myers, a “cousin-in-law.”

Architectural debris at the site where the White family house stood, September 2019.

James White was born c. 1877 in Washington, D.C. — likely in Henry and Clara White’s home in Broad Branch Avenue. According to the 1930 census, he and his wife Anna rented their home and worked as a construction laborer. More research is necessary to reconstruct his route to Pittsburgh and his life there.

Margaret Myers also appears to have been related to Henry White. She was born in Washington, D.C., in 1889. When Ella died, Margaret was living with her husband Henry at 1910 Irwin Street in the North Side. Ella left $50 in cash to her brother-in-law James and the Dalton Street home and its contents to Margaret. According to the inventory filed in Allegheny County, Ella’s house was well-furnished, with two bedrooms, a “front room,” kitchen, and a bathroom. She owned a radio and a “Victor talking machine” record player as well as chairs and tables, framed pictures, stoves, rugs, and lamps.

Ella’s assets included the real estate and more than $600 in bank deposits and nearly $1,000 in life insurance policies in her name.

Margaret and Henry Myers moved into the Dalton Street house. Henry worked as a porter and Margaret as a domestic. By the 1940s, their son and his family were renting part of the property. Margaret died in 1965 at age 75. The property at 50 Dalton Street remained in the Myers family until 1975, when it was sold for back taxes to the City of Pittsburgh. Margaret died at her son’s home in nearby Dornestic Street, another of the properties in James Fester’s 1902 subdivision.

Until recently, William and Ella White’s extended kin lived in this Dornestic Street home in Pittsburgh.

Making Connections

This detour into the lives of Henry White’s kin who lived in Pittsburgh may provide future researchers with sources to explore Washington’s White family and the early years of the Moses Order White’s Tabernacle No. 39. It also raises some interesting questions about the Black experience in Pittsburgh in the years preceding the Great Migration and African American community building at the neighborhood level in the years bracketing the turn of the 20th century. Wrapped up in those broad topics include such issues as land tenure and entrepreneurship. Those questions, however, await exploration by future researchers.

A note on sources

The information on Henry White and Washington came from my 2018 report, The River Road Moses Cemetery: A Historic Preservation Evaluation (copies on file, Montgomery County [Maryland] Housing Opportunities Commission, Montgomery County Planning Department, and District of Columbia Historic Preservation Office.

The information on William Miles White and Pittsburgh derived from research in Allegheny County land and court records and public records (e.g., census schedules, death certificates) digitized and posted on Ancestry.com. Context on their experience in Pittsburgh comes from the substantive contributions into African American history by the University of Pittsburgh’s Laurence Glasco and Carnegie Mellon University’s William Joe Trotter:

Glasco, Laurence A., and Federal Writers’ Project (Pa.), eds. The WPA History of the Negro in Pittsburgh. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2004.

Glasco, Laurence. “Double Burden: The Black Experience in Pittsburgh.” In City at the Point: Essays on the Social History of Pittsburgh, edited by Samuel P. Hays, 69–110. Pittsburgh Series in Social and Labor History. Pittsburgh, Pa: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1989.

Trotter, Joe W. “Reflections on the Great Migration to Western Pennsylvania.” Western Pennsylvania History: 1918 – 2018 78, no. 4 (1995): 153-158–158.

Trotter, Joe William, and Jared N. Day, eds. Race and Renaissance: African Americans in Pittsburgh since World War II. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2010.

© 2019 D.S. Rotenstein

Shortlink for this post: https://wp.me/p1bnGQ-3nI