North Meadowcroft Avenue in Mt. Lebanon, south of Pittsburgh’s city limits, is a quiet tree-lined suburban street. In 1965, the street became ground zero for testimony before a U.S. Senate committee investigating federal agency surveillance practices. Joseph “Frank” Grosso was racketeering kingpin Tony Grosso’s older brother and he was living in a home near the southern end of the street and around the corner from a home where his younger brother had lived in the 1950s. Cresson O. Davis was the Internal Revenue Service’s chief investigator in Pittsburgh and he lived five blocks north of the Grossos.

Frank Grosso had owned the stone-faced home since the 1930s. Davis was renting a ranch home that has had only two owners since it was built about 1952. There’s nothing remarkable about either home in a subdivision filled with period-revival and ranch houses. Neither house blares “the mob lives here” nor “fed in residence.” Perhaps that’s what made the street an attractive place that brought both men — on opposite sides of the law —together.

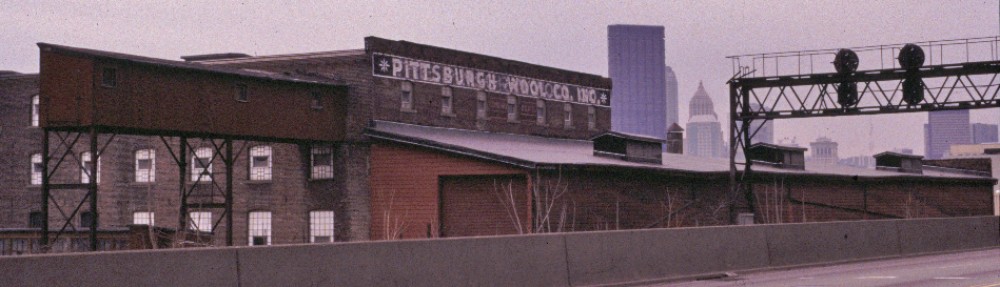

Former Grosso home.

Former Davis home.

The living arrangements might never have become public had it not been for the Senate investigation in 1965. The IRS had been using aggressive surveillance techniques, including illegal wiretaps and other listening devices, to snare mobsters and corrupt officials. Tony Grosso was one of the people caught up in the investigations. So was Pittsburgh Deputy Police Superintendent Lawrence Maloney. As a result of the Senate investigations, the IRS discontinued wiretapping and other methods to snare tax evaders.

But back to North Meadowcroft Avenue.

“What is your address, Mr. Davis?” Missouri Senator Edward Long asked.

After Davis replied, Long asked, “Can you tell us about a wiretap that you ran back into your basement and listened into down there?”

Davis declined to respond, citing the sensitivity of ongoing criminal investigations. He also didn’t get into many details about what and who was on the other end of the wiretap.

After more questioning, Davis conceded that the wiretap setup wasn’t in his basement. “It was on the first floor, in a den,” the IRS agent explained.

The tap remained active in the Davis home for several months. During this time, other IRS agents would enter the Davis home and service the equipment. Senator Long then asked about the agent’s wife: “I don’t want to get Mrs. Davis involved, but she also listened at times, didn’t she?”

Davis replied that she did not: “It was confidential, it was none of her business. I guess that is in the record. I may be in as much trouble at home as I am here.”

Davis didn’t live much longer after his testimony. The lifelong law enforcement officer who began his career in Washington, D.C., as a police officer died of cancer in 1966.

Tony Grosso. Pittsburgh magazine, 1977.

The Senate also called Grosso to testify. By this time, he and other Pittsburgh racketeers, including Meyer Sigal, had begun testifying about their protection payoffs to Maloney. Grosso claimed that he had been in the “the numbers business” but that he was now “in the real estate business.”

He told the Senate that Maloney had tipped him off to the IRS wiretap. The hearing veered well away from wiretapping and into the details about who ran Pittsburgh’s numbers rackets and how. Grosso also detailed how much and how frequently he paid bribes to corrupt officials.

Several times during the hearing Grosso replied, “I decline to answer that question on the grounds that it might incriminate me.”

Though Grosso asserted that he was a legitimate businessman after his conviction for failing to pay the federal wagering tax (a conviction later overturned by the U.S. Supreme Court), he also declined to tell the senators who had replaced him in the numbers racket or if he was somehow still involved.. “I decline to answer that question on the advice of my counsel,” Grosso said.

Grosso had good reason to be concerned about self incrimination. He remained one of Pittsburgh’s top numbers rackets leaders for the next several decades. His last convictions on state and federal charges were in the 1980s and he died in 1994 in a Pennsylvania prison hospital near Pittsburgh.

Grosso and Maloney were two of Davis’s high profile cases during the agent’s posting in Pittsburgh. Davis arrived in Western Pennsylvania in 1960 after a posting in Philadelphia. In Pittsburgh, Davis targeted several high-profile numbers rackets figures. I asked the son of one of those targets if he recalled his father ever speaking about Davis. “My Dad never complained about the feds. When they passed the RICO act he quit,” he told me.

After I told him about the Senate investigation of wiretapping and I explained why I was asking, he told me about his father’s use of telephones:

My father never talked on the phone unless it was a family member or friend not in the business. However on the few times he had to make a call we would drive around our neighborhood looking for a phone truck pretending to be fixing a wire on a pole. He thought the pay phones would be tapped.

As for those phone trucks he described, read about Pittsburgh’s wiretap truck in this earlier post.

Catch up on all the MobsBurgh posts and follow us on Twitter @the805project. Coming soon, a visit with a popular drink manufacturer.

© 2021 D.S. Rotenstein

Shortlink for this post: https://wp.me/p1bnGQ-3K6

Superb work thank you for this! A bartender I know had an older friend who worked for Grosso in the 70s.