What a year. I did a lot of writing about a diverse array of subjects, including housing, social justice, orphanages, ethnic clubs, books about Pittsburgh and its suburbs, and crime — lots of crime. I had the good fortune to meet many wonderful people willing to tell me their stories. The editors who published my work helped me to bring those important stories to readers, some of whom became collaborators on future stories. None of what I accomplished in 2024 would have happened without their help.

I was humbled by the amount of trust so many people placed in me and the risks some of them took to collaborate with me to help tell their stories. One woman whose former neighborhood is being destroyed by her local government turned the tables on me in a conversation we had in August in her mother’s suburban living room.

“How did you get into doing this particular type of work,” she asked me.

“What do you mean,” I replied.

The woman explained:

She’s talked to 100 people. No one’s ever come to talk to her before. Not once. Not once, certainly not twice.

So what intrigued you to dig, to delve?

After more than 20 years of trying to get the attention of local, state, and federal officials, civil rights organizations, and journalists, I was the only reporter who didn’t walk away from her mother’s story.

The woman’s statement underscores how much my experience in public history and ethnography informs my journalism.

Off the printed page and device screens, I did several public programs, including a community history talk celebrating the South Side Carnegie Public Library branch’s centennial and two programs for the Jewish Association on Aging’s Weinberg Terrace residents.

Through Steel City Vice, my public history engagement experiment, I began leading organized crime history walking tours in Pittsburgh’s South Side neighborhood. Though the route and script were constant, each tour was different because of the people who participated. Some of the people who took the tour had family members who were in numbers gambling or themselves participated in the culture. A retired vice cop took one of the tours and added fleshed out my narratives in some colorful and unexpected ways.

Greater Pittsburgh Festival of Books organizers invited me to moderate a true crime panel in May. Authors Paul Hodos, Richard Gazarik, and Jason Kirin spoke about their books documenting key episodes in Pittsburgh crime history in one of the festival’s best-attended sessions.

This year I also picked up two Pittsburgh Black Media Federation Robert L. Vann awards for excellence in journalism. The category under which one of them one: Sports. Anyone who knows me and my lifelong aversion to sports would be just as surprised as I was. I also was a finalist for two Press Club of Western Pennsylvania Golden Quill awards.

Two films and one podcast featured my work documenting the erasure of Black history in Silver Spring, Maryland, and Decatur, Georgia. Curtis Crutchfield grew up in Silver Spring’s Lyttonsville neighborhood and he produced “Linden Lyttonsville” to tell the community’s story.

Piedmont University film student Jarrett Ray’s family has deep roots in Decatur, Georgia’s, Beacon Community. For his capstone project, he produced “Displaced But Not Erased” to tell the community’s story through his family’s experiences. Ray drew on my research into the erasure of Black history in Decatur and used several of my photos and footage shot during my work there.

Urban planner Zoe Roane-Hopkins visited Silver Spring’s Acorn Park for an episode in her Mud Kitchen podcast series. She first encountered the park and then found my work documenting how public art there whitewashes Silver Spring’s history.

2024 in Words and Pictures

The year started strong with an assignment to investigate the history of racially restrictive deed covenants in Pittsburgh. Building on my 2023 essay on the history of redlining in Pittsburgh published by the Mapping Inequality project, PublicSource published my covenants article and storymap visual supplement in April.

The racially restrictive deeds covenants investigation led to a follow-up feature on the history of a Penn Hills neighborhood, Lincoln Park, as an early historic Pittsburgh area Black suburb. PublicSource published “‘We all stayed.’ Penn Hills, once a suburban landing pad for Black households, now risks disinvestment and erasure of history” in June.

Digging into Pittsburgh’s history of race and real estate led to a two-part series published in Pittsburgh City Paper about Fox Chapel as a sundown town. The first article, “By some metrics, Fox Chapel is a sundown town,” came out in April. It told the story of how Fox Chapel, located about six miles north of downtown Pittsburgh, became an exclusive and all-white (except for domestic employees) borough in the 1930s. My reporting documented how Fox Chapel uses zoning to maintain high barriers to entry into the community.

To say that the April Fox Chapel article generated a lot of discussion is an understatement. Readers flooded Pittsburgh City Paper’s social media channels with comments. Several readers also reached out to tell stories of more recent episodes of racial bias in Fox Chapel. Marshall McDonald, a Grammy-winning musician who grew up in Fox Chapel, was one of the readers who contacted the paper. In the early 1960s, McDonald’s family became the first Black homeowners in Fox Chapel. In April, Pittsburgh City Paper published “Fox Chapel fallout: what locals of color say about the borough’s history of racism.”

Marshall McDonald told me about how a Carnegie Mellon University professor helped his family buy their home in 1964. Economics professor Richard Cyert had lived in Fox Chapel with his family since 1957. He and another CMU professor worked with Marshall’s parents to buy a home a couple of doors down from the Cyerts. I interviewed Richard and Margaret Cyert’s three daughters for the second City Paper article about Fox Chapel. The Cyert sisters told me a remarkable story about their family: Richard Cyert’s parents had been part of the Orphan Train movement. Born Jewish in New York City, they travelled separately as young children to Minnesota. They both were raised Catholic and met in their families’ church and married. The Cyert sisters used DNA and archival research to piece together their family story. In December, PublicSource published “How ‘orphan train’ origins informed CMU’s trailblazer — and brought diversity to Fox Chapel.”

My reporting on Penn Hills and Black history led several longtime residents to email me in June. “As I read your report, I want you to know that there are several important persons, [who] lived in our neighborhood, who should be mentioned,” wrote one woman in her 90s who has lived in Penn Hills since the 1950s. “Those of us that are still here, are proud of our neighborhood and have fought to keep our community, even though many of us feel at times Penn Hills, political structure did not want Lincoln Park, because of ‘white flight’ and we became 99.% African American.”

That email led to another five months of reporting. Pittsburgh City Paper agreed to publish the results in a two-part series exposing 60 years of environmental racism in Penn Hills. I closed out 2024 with the publication of the first part, “Penn Hills has long been home to a Black middle-class community, but some claim environmental racism is demolishing it — literally.” The second part and an online multimedia package will be published in early January 2025.

While reporting on housing issues in Penn Hills, I met Wynona Harper and learned about a new supportive housing project she is proposing to build. Harper founded te nonprofit Jamar’s Place of Peace after losing her son, Jamar Hawkins, to violence in 2013. Her organization provides food and other social services to Penn Hills residents. Long annoyed by the municipality’s neglect of Lincoln Park and the increasing number of vacant and abandoned lots, Harper embarked on expanding the Jamar’s Place of Peace portfolio by developing five housing units, a store, a community garden, and chicken coops on lots that Penn Hills demolished in the program described in my City Paper series on environmental racism.

There was a lot more to my social justice reporting than housing. In February, Pittsburgh City Paper published “A forgotten 1909 incident shows how Pittsburgh has — and hasn’t — moved on from racialized violence.” I also wrote about another historical episode of racial violence for NEXTpittsburgh. In 1933, corrupt cops in Beaver County, Pennsylvania, forcibly removed 46 Black people by piling them into trucks and driving them to the West Virginia state line. The men and women were told to leave Pennsylvania and to never return. NEXTpittsburgh published “Surprising details about the Beaver deportation that forced 46 Black people to leave the state” in September.

Housing issues, though, were a dominant theme for me in 2024. In June I met an unhoused man with a compelling story in Pittsburgh’s Hill District. I was there to photograph a commemorative plaque marking the former location of a business with deep ties to the Hill District’s Black community. The business had been owned by a Lincoln Park resident whose home Penn Hills demolished in 1996.

While I was shooting photos, a man in a wheelchair inside the adjacent bus shelter angrily told me that he didn’t want me to take his picture. I agreed and deleted the photos with him in the background from my DSLR camera and phone. It wasn’t a big deal because I knew I needed to return in better lighting conditions.

As I was packing up to leave, the man in the bus shelter asked me why I was taking the pictures. He asked if I worked for “the Councilman.” I said no and told him that I was a reporter shooting photos for a story about Penn Hills.

I told the man my name and asked for his.

“Norman White,” he replied. “I was hoping that you were somehow connected with the community and maybe you could talk to the councilman or somebody.”

White began telling me his life story story, including the events leading up to his recent eviction, which left him living on the street in the Hill District and desperate to find electrical outlets to charge his chair. I asked him if I could turn on a recorder and he consented. He explained again for the recorder his route to the Centre Avenue bus shelter where we were speaking. About 10 minutes into the recording I said, “You asked me to not take your picture back there. Do you mind if I take your picture?”

He agreed to allow me to photograph him, with some firm ground rules. We spoke for another 20 minutes before I had to leave to meet a photographer in a Penn Hills church.

I returned to the Hill District several times over the next week. Each time, I brought water and the type of soda White likes. We spoke several more times and he allowed me to continue photographing him. As a brutal heatwave settled over Pittsburgh, I connected White with Allegheny County Council member Bethany Hallam. She arranged for someone to bring White some new clothes and a cellphone. Hallam also paved the way to get White into a shelter.

White’s conditions for speaking with me and allowing me to take pictures were meant to respect his dignity and to protect him. Photography of and reporting on unhoused people are fraught issues. White wanted me to tell his story and show people his situation. He wanted people in power to understand his situation through words and pictures. Among the conditions White set: I wasn’t supposed to spend too much time with him and draw unwanted attention from people who might think I was associated with law enforcement. I agreed to leave as soon as Hallam’s contacts arrived and I did. Three weeks later, Pittsburgh City Paper published my heavily illustrated story, “Dignity is being unplugged in the Hill District.”

I caught some flak from unexpected sources in the aftermath of my story about White. Within a day of it being published, a Hill District organization mentioned in the story removed all of my content from a website it had created in collaboration with a regional university. Late last year I signed a contract with that university to write several articles about Hill District history for the site. By June, I had written five: four had been published and one was in editing. The history professor with whom the organization is working didn’t know about the unilateral decision to remove my articles. I was surprised but it wasn’t the first time that an organization had decided to erase my work. It happened several times in Decatur, Georgia. Unlike the folks in Decatur, the organization didn’t also scrub references to my work.

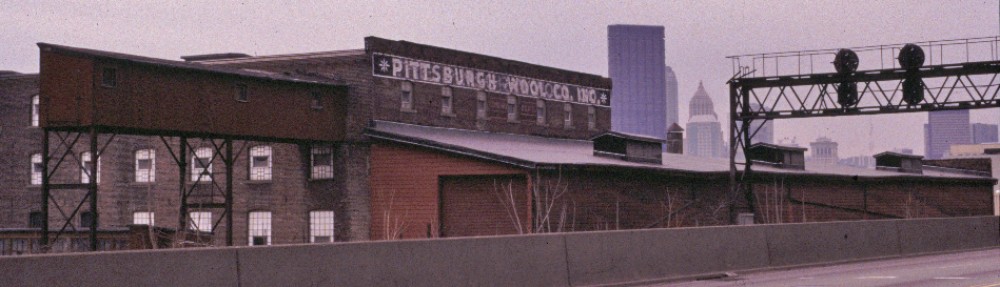

My story about the terrible state of record keeping in Allegheny County also generated a lot of buzz. More than 200 years of invaluable historical records are being lost, thrown away, or allowed to rot in a system that state officials first recommended improving in the 1984. Little has changed since then and I was the latest in a string of reporters going back 30 years. One retired reporter I interviewed wrote about the county’s record keeping in 2001. She told me that Allegheny County’s North Side Records Center “reeked of neglect.” I could only see the neglect from the outside — Allegheny County officials wouldn’t allow me into the building. NEXTpittsburgh published my article, “Many of Allegheny County’s historical records are slowly rotting away,” in May.

It’s a little long …

Whew, that’s enough for one blog post. This time I get to cut off myself instead of leaving it to one of my very patient and generous editors. Come back in a week for the final part of my look back on 2024. Any recap isn’t complete without some bootlegging, gambling, and prostitution stories. I couldn’t possibly end the year without talking about former Pittsburgh Mayor Sophie Masloff’s family’s ties to organized crime or the so-called “World’s Greatest Conman’s” ties to Pittsburgh or my trip up and down the three rivers to tell the story about the city’s colorful floating speakeasies and casinos.

The final installment: A year in vice and the arts.

© 2024 D.S. Rotenstein

Shortlink for this post: https://wp.me/p1bnGQ-46h