Last week I attended the Vernacular Architecture Forum conference in Washington. Conferences are great events that give consultants (like yours truly) a chance to speak with colleagues from around the country. At the banquet I had a long conversation with someone who does cultural resource management work out in the Pacific time zone. We commiserated about the ranks of CRM firms who send out archaeological technicians to identify historic buildings and landscapes. We lamented the lack of regulatory oversight by federal agencies and state historic preservation offices to ensure that historical research and analysis were being done by historians and not archaeologists being kept billable by mega consulting firms.

Our exchange brought to mind similar conversations I had carried out with the late Ned Heite. Some of these took place on email lists like ACRA-L. One memorable one took place in June 2000. Ned aptly titled it “Interchangeable parts. Ned had responded to one of my posts, which read in part:

As I sit here looking through yet another Section 106 report on above-ground architectural resources prepared by archaeologists and rejected by a SHPO, I wonder when anyone in this industry is going to understand the “American System.” Interchangeable parts are things that are bulk or mass-produced that can be swapped out for in-kind identical parts in a tool, machine, whatever. If you’re going to apply the interchangeable parts model to the CRM industry, swap parts in offices, jobs, etc. with like parts. Don’t send archaeologists out to do what an architectural historian should do. After all, when your brakes go on your car, you’re not goign going to replace them with spark plugs, now are you?

Ned’s post read:

Bravo, David. As one who is “certified” by the SHPO in all the disciplines, I second your statement. By coincidence of employment, I have managed to push all the buttons for the Secretary’s standards. This does not, of course, mean that I know what I am doing.

Along those same lines, one of my pet peeves is the portable historian. When the weather turns bad, the state archives are flooded with field techs and others, who are supposed to be doing historical background research. Most of them haven’t the foggiest notion of historical research or the history of the locality.

Local history research is an arcane field, best left to people who are specialists in a very narrow geographical area. Yet CRM firms routinely dispatch unqualified staff to research the background history of places they can’t even pronounce!

The standards should be tightened, exponentially, and the historical background should be mandated to be done by a person with local expertise, who is also recognized as a competent CRM historian. And remember that a CRM historian is a very different creature from a kid with a fresh MA in some kind of generalized history.

Little has changed in the 10 years since that exchange. Large engineering companies with cultural resource management divisions continue to deploy teams of archaeologists to do historians’ work. I recall observing the archaeologists return from the field and in mixed horror and amusement watched them spend countless hours (and clients’ dollars) trying to match fuzzy photos of buildings with what they could find in Virginia and Lee MacAlester’s generic Field Guide to American Houses.

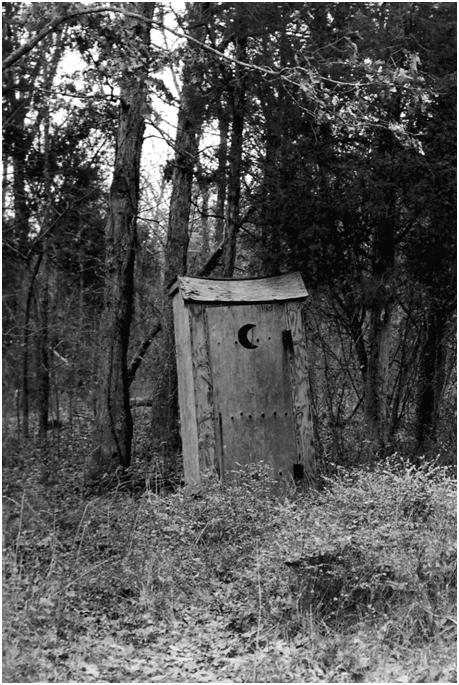

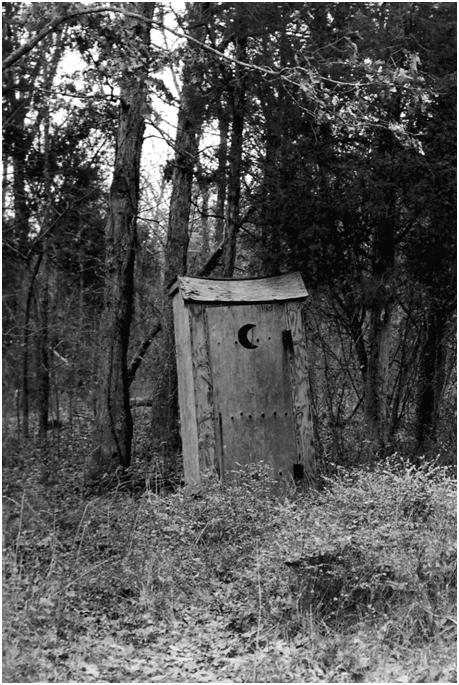

I still have the wonderful photo of a Prince William County privy that one archaeologist (who did not do the fieldwork, but who was given a stack of photos to describe) characterized in her report as a “desk.”

History in the crapper: one archaeologist’s “desk.”

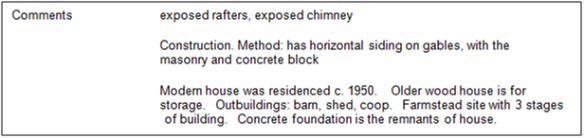

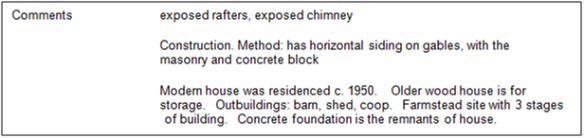

Among some of the choice architectural descriptions penned by archaeologists are these:

Like this:

Like Loading...

![]() search cost?

search cost?