By David S. Rotenstein

[08/22/2011: Update: Read the follow-up post on newly identified photos showing the construction of the Fort Reno “Cartwheel” facility in Washington, DC]

In 2004 the State of Maryland was both project proponent and regulatory reviewer in the Section 106 consultations tied to the construction of a proposed telecommunications tower at Lamb’s Knoll, a mountaintop ridge that straddles Washington and Frederick counties west of Frederick. A Federal Communications Commission licensee, the State was required to identify historic properties, evaluate their significance under the National Register Criteria for Evaluation, and determine whether the proposed project would adversely affect properties listed in or eligible for listing in the National Register of Historic Places. Properties likely affected at Lamb’s Knoll included the Appalachian Trail, a 1920s fire observation tower turned telecommunications tower, and a Cold War-era army facility.

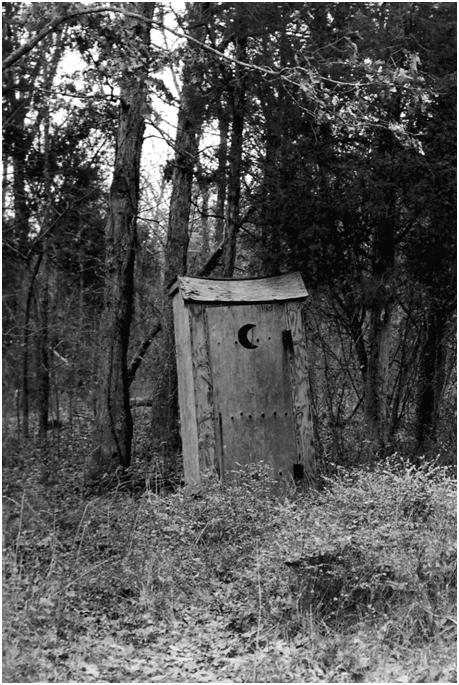

Maryland’s agency for emergency telecommunications infrastructure retained a cultural resource management firm to conduct the Section 106 compliance studies. The firm’s initial 2003 report noted the presence of nearby nineteenth century farmsteads and surrounding Civil War battle sites, but there was no mention of the twentieth century resources.[1] The Maryland Historical Trust (the state historic preservation office) reviewed the 2003 report and concurred with its authors that no historic properties would be affected by construction of the proposed tower. Located less than 500 feet from the proposed tower site and rising approximately 100 feet above the mountaintop, the former Cold War facility was notably absent from all discussions turning on historic preservation and the proposed tower. Hidden in plain sight and visible from miles around, the Lamb’s Knoll facility is one of a handful of continuity of government sites built in Maryland, Pennsylvania, Virginia, West Virginia, and Washington, D.C., that were designed to house large numbers of federal officials in underground bunkers while the exposed concrete towers that housed sophisticated radio equipment kept communications open among the survivors, the military, and civilian populations.

This article stems from my involvement in that 2004 project. I was retained by a coalition of environmental groups including the Harpers Ferry Conservancy and the National Trust for Historic Preservation to evaluate the historic properties the groups believed that the State’s consultant failed to identify in the initial round of Section 106 consultation. Between 2001 and 2008 I did many Section 106 projects for FCC licensees and I had been working on histories of postwar telecommunications networks.[2] By the time I had been brought into the Lamb’s Knoll project I was sensitive to the historical significance embodied in telecommunications facilities like the repurposed fire lookout tower and the Cold War facility.