By David S. Rotenstein

[08/22/2011: Update: Read the follow-up post on newly identified photos showing the construction of the Fort Reno “Cartwheel” facility in Washington, DC]

In 2004 the State of Maryland was both project proponent and regulatory reviewer in the Section 106 consultations tied to the construction of a proposed telecommunications tower at Lamb’s Knoll, a mountaintop ridge that straddles Washington and Frederick counties west of Frederick. A Federal Communications Commission licensee, the State was required to identify historic properties, evaluate their significance under the National Register Criteria for Evaluation, and determine whether the proposed project would adversely affect properties listed in or eligible for listing in the National Register of Historic Places. Properties likely affected at Lamb’s Knoll included the Appalachian Trail, a 1920s fire observation tower turned telecommunications tower, and a Cold War-era army facility.

Maryland’s agency for emergency telecommunications infrastructure retained a cultural resource management firm to conduct the Section 106 compliance studies. The firm’s initial 2003 report noted the presence of nearby nineteenth century farmsteads and surrounding Civil War battle sites, but there was no mention of the twentieth century resources.[1] The Maryland Historical Trust (the state historic preservation office) reviewed the 2003 report and concurred with its authors that no historic properties would be affected by construction of the proposed tower. Located less than 500 feet from the proposed tower site and rising approximately 100 feet above the mountaintop, the former Cold War facility was notably absent from all discussions turning on historic preservation and the proposed tower. Hidden in plain sight and visible from miles around, the Lamb’s Knoll facility is one of a handful of continuity of government sites built in Maryland, Pennsylvania, Virginia, West Virginia, and Washington, D.C., that were designed to house large numbers of federal officials in underground bunkers while the exposed concrete towers that housed sophisticated radio equipment kept communications open among the survivors, the military, and civilian populations.

This article stems from my involvement in that 2004 project. I was retained by a coalition of environmental groups including the Harpers Ferry Conservancy and the National Trust for Historic Preservation to evaluate the historic properties the groups believed that the State’s consultant failed to identify in the initial round of Section 106 consultation. Between 2001 and 2008 I did many Section 106 projects for FCC licensees and I had been working on histories of postwar telecommunications networks.[2] By the time I had been brought into the Lamb’s Knoll project I was sensitive to the historical significance embodied in telecommunications facilities like the repurposed fire lookout tower and the Cold War facility.

Aided by an active Internet community devoted Cold War communications sites, especially Virginia resident Albert LaFrance’s copiously illustrated “A Secret Landscape: America’s Cold War Infrastructure” Web site and Cold War Communications listerv, I began to find the cracks in the top-secret cloak that enshrouds the Lamb’s Knoll facility and its sister sites throughout the Mid-Atlantic.[3] LaFrance’s Secret Landscape site includes declassified document scans, articles from popular and trade publications, and first-person accounts from the engineers and others who built, maintained, and operated private- and public-sector Cold War communications networks. Although the Lamb’s Knoll project ended in 2004 when the FCC determined that the State of Maryland’s proposed tower would not adversely affect historic properties, my interest in the Cold War sites continued and in early 2010 I was able to conduct an oral history interview with a former army sergeant who spent two years assigned to one of the facilities. This article presents a brief overview of the facilities and the challenges they and other top-secret military and national intelligence sites pose to preserving the recent past.

When terrorists struck the morning of September 11, 2001, Vice President Richard Cheney was whisked from his Washington office to a secure “undisclosed location.” Cheney’s undisclosed location is rumored to have been a Cold War era facility buried deep beneath Raven Rock Mountain near the Pennsylvania-Maryland border.[4] Located east of Waynesboro, Pennsylvania, the Raven Rock Military Complex is also known as Site R and it was designed as the Alternate Joint Communications Center (AJCC) where senior military officials were to be taken in the event of a nuclear attack. Site R was among the first relocation facilities built in the 1950s and early 1960s as federal planners conceived of and realized a Federal Relocation Arc extending outwards from Washington where key documents and people could be sheltered during and after a nuclear exchange.[5]

The Federal Relocation Arc included above- and below-ground sites located within a 300-mile radius of the nation’s capital. Sites included existing buildings like the Greenbrier Hotel and college campuses throughout the region.[6] The sites were administered through the Executive branch’s White House Military Office. Communications personnel were attached to the White House Communications Agency (WHCA). The Presidential Emergency Sites were “literally holes in the ground, deep enough to withstand a nuclear blast and outfitted with elaborate communications equipment,” recounted former White House Military Office Director W.L. Gulley.[7] According to Gulley, funds to support the sites wound their way through a circuitous route in the Defense Department. “Authorization to spend the money, although it was allocated to the Army, was given to the Navy – specifically, the Chesapeake Division, Navy Engineers – who didn’t know what the fund was for.”[8] All oversight for these facilities originated in the White House Military Office.[9]

The sites in the Arc key to ensuring open lines of communications were built in a network that relied upon line-of-sight microwave technology, i.e., each transmitter and receiver had to have an unobstructed line-of-sight between its nearest neighbor for the network to be viable. These microwave hops were usually no more than fifty miles apart. “I’m assuming that when they did their studies they knew specifically where the main terminals were going to be and they looked for locations that they had line of sight to,” explained John Cross, a retired Army sergeant who was assigned to WHCA. “And they were all, you know, within probably maybe forty miles of each other.”[10]

According to John Cross and other former government employees there were 75 Presidential Emergency Facilities among the 90 or so Federal Relocation Arc sites. Only a handful of the properties were designed as a key communications node in the continuity of government microwave network. The sites were known by their locations, i.e., Raven Rock or Lamb’s Knoll; and, they each had codenames, all of which began with the letter “C”:

|

Presidential Emergency Facility Sites |

||

| Site Code Name | Other Name | Location |

| Crown | The White House | Washington, D.C. |

| Cartwheel | Fort Reno | Washington, D.C. |

| Crystal | Mt. Weather | Berryville, Virginia |

| Corkscrew | Lamb’s Knoll | Frederick County, Maryland |

| Cowpuncher | Martinsburg | Roundtop Summit, Virginia |

| Cannonball | Cross Mountain | Mercersburg, Pennsylvania |

| Cactus | Camp David | Thurmont, Maryland |

| Creed | Site R (Raven Rock) | Waynesboro, Pennsylvania |

Each of the sites included a 100-foot cylindrical tower, two-thirds of which was solidly built to house transmitters and receivers, supply rooms, and quarters for the skeleton staff which oversaw the facilities around the clock. The upper portions of the towers held parabolic antennas aimed towards the next facility in the network. These antennas were shielded by radio frequency-transparent plexiglass that protected the antennas from the elements and concealed them from view while enabling radio waves to pass through. The towers were connected to elaborate underground bunker complexes and entry to the facilities was through massive blast doors.

Because the towers were highly visible yet top-secret, no official explanations of their functions ever were released. Locals near the Lamb’s Knoll site speculated that the tower was a missile silo. Cannonball, where Cross was stationed, and Camp David’s Cactus site were believed to be water tanks. “People around Mercersburg thought it was a water tower,” Cross recalled. “We used to buy water from the City of Mercersburg and we had a water tanker that we’d haul water back up to the mountaintop so they saw that and they saw, you know, the water tanker and they just figured that they were getting better water pressure that way.”[11] During Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev’s 1959 visit to Camp David with President Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Cactus facility’s tower sported an observation deck and signage to reinforce the perception that the structure was in fact a water tower.[12]

Cannonball Tower Site, Mercersburg, Pennsylvania. Photograph by Cham Green and provided by John Cross.

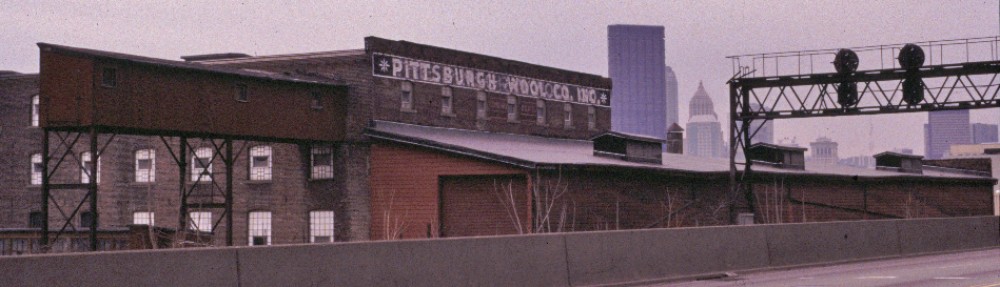

The Cartwheel site is located among early twentieth century water towers in Washington’s Fort Reno Park: “Radar and other sound-sensitive antennas, dishes, and horns were installed atop a new brick tower at Reno — the one that does not hold water. The underground communications center reportedly links the White House with other larger centers in the Middle Atlantic states.”[13]

Cartwheel Site, Fort Reno Park, Washington, D.C. The Cartwheel tower is the leftmost structure. The two masonry buildings on the right are historic water towers. Photograph by David S. Rotenstein, 2010.

Since the facilities were top-secret, few detailed descriptions of their interiors have surfaced. John Cross never photographed Cannonball or the other facilities he visited while assigned to WHCA. Cross has prepared several line drawings illustrating the interiors of Cannonball, Cactus, and Cartwheel. According to Cold War communications enthusiasts, the concrete towers were designed to deflect the force of a nuclear blast. Cross explains their construction,

Well it was solid concrete. You know the air system was filtered so that if anything did happen all the air intake would be shut down and you had a filtration system. Everything was I guess primarily engineered you know with the concrete. Now you know there was always some possible problems with the antenna decks where we had spare microwave dishes that could be put in temporarily if anything happened that, you know, a blast would be close enough to tear off some of the dishes. We had spare dishes that we could put in in a fairly short period of time, that we could replace them. But the structure itself with concrete was really about the biggest thing.[14]

Listen to John Cross describe the facilities:

MP3 clips from the April 2010 interview

John Cross describes going to work for the White House Communications Agency

John Cross describes the Presidential Emergency Facilities

Hiding in plain sight: concealing the facilities

Planning for the unthinkable: nuclear war

By the early 1970s the Presidential Emergency Facilities were being decommissioned. Cross recalls closing down Cannonball in 1970 shortly after significant upgrades were installed. Changes in communications technology and continuity of government plans obviated the 1950s facilities. Most were transferred from Army control to other agencies. Corkscrew (Lamb’s Knoll) and Cartwheel (Fort Reno) were acquired by the Federal Aviation Administration and their towers remain in use. Mt. Weather remains a top-secret facility and Cannonball was abandoned and sold, its tower exposed to the elements and vandals. The towers at Cactus (Camp David) have been demolished and Site R is abandoned.

Each of the remaining Presidential Emergency Facilities may at some point become part of a Section 106 case in which the property’s eligibility for listing in the National Register of Historic Places must be evaluated. Recent Past properties, especially those tied to military and intelligence infrastructure present unique challenges stemming from a lack of understanding of recent past resources, biases against properties of such recent vintage, and the added layer of secrecy inherent in such properties.[15] In the Lamb’s Knoll Section 106 consultation from 2004, the State of Maryland’s consultant wrote that the Presidential Emergency Facility could not be evaluated for listing in the National Register because of its top-secret status. The Maryland Historical Trust agreed:

Constructed circa 1962, the U.S. Army Facility was evaluated against Criteria Consideration G for Exceptional importance and subsequently recommended as ineligible since the history of the facility and photographs are unobtainable due to security concerns. Until such time that the facility is no longer top-secret and the significance can be examined more thoroughly, the Trust concurs that the Lambs Knoll U.S. Army Facility is ineligible for the National Register.[16]

As the federal agency responsible for complying with Section 106, the FCC issued comments that reinforced the State of Maryland’s. “The MDSHPO [Maryland Historical Trust] further advises that it is not possible to determine if the Federal Facility is eligible given the secrecy surrounding that property and its mission,” wrote the FCC in its final opinion issued in July 2004.[17]

Sites like Cartwheel, Corkscrew, and Cannonball were critical continuity of government sites during the Cold War. Their highly visible towers became part of an industrial landscape defined by telecommunications infrastructure essential to the information-based third industrial revolution. Beyond their highly function roles in the ubiquitous military industrial complex, they also were places where people worked and lived daily. “I had a lot of fun, you know, even though it was a job, I had a lot of fun,” recalled John Cross during our twenty-first century interview using Skype. “You know, the funny thing about it, I worked with people that were both at Crystal and Cadre and Cartwheel for years after we closed down those sites. But we never discussed what went on at those locations.” As historic preservation practice matures and greater significance is attached to recent past resources, perhaps more may be known about these sites, their roles in American and global culture, and the people who built them and worked there.

Acknowledgments

Thanks are due to John Cross for sharing his memories in what turned out to be my first oral history interview conducted by Skype. John read a draft of this article and I appreciate his keen eye (and ear) for detail. Thanks are also due to the test readers who helped work out the multimedia kinks. The 2004 fieldwork at Lamb’s Knoll was sponsored by the Harpers Ferry Conservancy and the Recent Past Preservation Network and Society for Industrial Archeology have published the results of my work on telecommunications facilities in their newsletters and in the SIA journal. Albert LaFrance has been a reliable and valuable source of information on all things related to telecommunications infrastructure history. As always, I take full responsibility for the contents of this article.

[Note: This article originally was written for the Recent Past Preservation Network newsletter and was slated to be published in June 2010. I had intended to supplement the RPPN article with a blog post including the audio clips.]

Notes

[1] Laura H. Hughes and Gerald M. Maready, Lambs Knoll Telecommunications Tower, Frederick County, Maryland, Report Prepared for Maryland Department of Budget and Management, Office of Information Technology (Washington D.C.: EHT Traceries, Inc., November 2003).

[2] David S. Rotenstein, “Radio Towers: New Federal Policies Threaten the Legacy of America’s Communications Industry,” Society for Industrial Archeology Newsletter 32, no. 3 (2003): 1-2; David S. Rotenstein, “Towering Issues and the FCC,” Forum News 10, no. 6 (2004): 1-2, 6; David S. Rotenstein, “Communications Towers: An Endangered Recent Past Resource,” RPPN Bulletin 2, no. 1, Newsletter of the Recent Past Preservation Network (2004); David S. Rotenstein, “New Federal Policies Endanger Historic Engineering Sites,” Society for Industrial Archeology Newsletter 34, no. 3 (2005): 17; David S. Rotenstein, “Towers for Telegrams: The Western Union Telegraph Company and the Emergence of Microwave Telecommunications Infrastructure,” IA, The Journal of the Society for Industrial Archeology 32, no. 2 (2006): 5-22; David S. Rotenstein, Western Union Telegraph Company Jennerstown Relay, Westmoreland County, PA, U.S. Department of the Interior, Historic American Engineering Record (HAER), No. PA-636 (Washington: Library of Congress, 2007), Prints and Photographs Division, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/pa4014/.

[3] Albert LaFrance, “A Secret Landscape: The Cold War Infrastructure of the Nation’s Capital Region,” n.d., http://coldwar-c4i.net/index.html.

[4] Steve Goldstein, “’Undisclosed location’ disclosed A visit offers some insight into Cheney hide-out,” The Boston Globe, July 20, 2004, http://www.boston.com/news/nation/articles/2004/07/20/undisclosed_location_disclosed/

[5] David F Krugler, This Is Only a Test: How Washington, D.C. Prepared for Nuclear War, 1st ed. (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006).

[6] Ibid., 95-96.

[7] Bill Gulley and Mary Ellen Reese, Breaking Cover (New York, New York: Simon and Schuster, 1980), 35.

[8] Gulley and Reese, Breaking Cover, 36.

[9] Gulley and Reese, Breaking Cover, 36; John C. Maxwell III, “Current Information on Abandoned Site 2 (Cannonball) at Cross Mountain in Franklin County, Pennsylvania,” Memorandum for the Record, 31 May 1988, Scanned document available online at <http://coldwardc.homestead.com/files/cannonball/maxwell1.htm>.

[10] John Cross, “Interview,” interview by David S. Rotenstein, Digital Audio (Skype), April 13, 2010.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ted Gup, “FEMA: How the Federal Emergency Management Agency learned to stop worrying — about civilians — and love the bomb,” Mother Jones, 1994, http://motherjones.com/politics/1994/01/fema.

[13] Judith Beck Helm, Tenleytown, D.C., Country Village into City Neighborhood (Washington, D.C: Tennally Press, 1981), 225.

[14] Cross, “Interview.”

[15] Amy Worden and Elizabeth Calvit, “Preserving the Legacy of the Cold War,” CRM 16, no. 6 (1993): 28-30; Mary K. Lavin, Thematic Study and Guidelines: Identification and Evaluation of U.S. Army Cold War Era Military-Industrial Historic Properties (U.S. Army Environmental Center: Aberdeen Proving Ground, Maryland, 1998).

[16] J. Rodney Little to Ellis Kitchen, “State of Maryland Emergency Communication Tower,” Letter, April 8, 2004.

[17] Memorandum Opinion and Order (Federal Communications Commission, July 2, 2004).

© 2010 David S. Rotenstein

Shortlink for this post: https://wp.me/p1bnGQ-81

A few minor nitpicks…. The Greenbriar was a Congressional site; not part of the Executive Branch system. Also, some might read the above to imply Site R was shuttered; when it was Creed at Site R that was, along with the rest of the network.

Nitpicking a nitpicker: It is Greenbrier, not Greenbriar.

To the FAA (or whoever truly operates the remaining sites these days) — On behalf of those of us Cold War history buffs who became familiar with the hardened, sensitive sites you inherited & used our discretion to not publicly discuss them out of a respect for their current mission, I apologize for the behavior of the researchers who seem not to care. Your OPSEC regarding them sucks, but that’s no excuse.

The public has the right to know. The same info could be gotten from the Freedom of Information Act. Your all bent out of shape over sites that have been dormant for over 30 years. Get a life on the OPSEC.

Wondering if this John Cross is the same John Cross that came to Untied Tel in Mansfield, in late 70’s?

TNX

Yes, this is the same John Cross. I was serving in the Agency with him when he left to go to work for United in 1973 or 74.

Hi, Paul!

Yes you have the same person, Its strange how we can find people that we haven’t talked to for years. what are you up to these days? I am currently living in a NW suburb of Chicago and have been since 1989, when I left Lexington ( for the second time). Send me your e-mail address and we can catch up with each other!

John

Bob Harlan ran across this and sent to me. Bob into these old telephony networks/sites.

ntaceng@embarqmail.com just in case

well written… ever find the map with ‘Navy Sites 1-60’?

What is the “Navy Sites 1-60” map?

Yes, Site R is still very much alive — it’s two miles down the road from where I sit at the moment, and from what you can see of the parking lot from PA 16, it’s pretty full

There were two complexes connected with Site R. Creed was the comm tower located just 1/2 mile west of the crest of Raven Rock on a side hill with line of sight to Camp David. Stacking arrangement was different than Cannonball in that only the top two floors of the tower were above ground. Entrance was through a tunnel in the side of the hill. It was connected by cable to Site R where the Presidential quarters, WHCA switchboard, and the secure communications equipment were located.

Great article.

Site R is part of BRAC and more and more job announcement are coming out for Site R. Look it up on google or bing maps great pictures and there not blurred out yet. One question in Baltimore County a place called Grace’s Quarters there’s a FEMA tower located there and was always rumors a FEMA/presidential bunker was there. Now its just a part of Aberdeen Proving Grounds and it used to used for chemical testing. Just wondering if you have any insight on that?

David,

For those of us interested in old telephone, communications, and interesting underground facilities, this was a fantastic write up.

Can you venture into the AT&T project site located just south of Cannonball in MD, or is that still classified??

Thanks

Gary

Thanks Gary. I will email you about your question.

I always thought it was interesting how close those two sites were.

And the proximity of the hardened site in relation to each other.

HearthStone been rumored to be inactive or used by FEMA.

Judging from the number of vehicles in the parking lot, somebody is working there. I count over 30.

NO and Yes

I live at the bottom of the mountain where connonball is located …..lived here all my life! I know and everyone knows thats a no trasspassing zone!

Years ago some guys hand glided off the top & one died when he fell after that they welded the doors back up. I was up there as a teenager & its a shame people hafe to destory history!!! I’v always wondered what really went on up there when it was in operation….it must be top secret and really impotant that info still can’t be told about it even after all these years that its been shut down! The strangest thing of it all…. for being such a small town and not much action goes on here but…..Do you know 2 planes have crashed out here in the sides of the mountain right by AT&T? Anyone else find that stange?

Nicki

I worker in the tower from 1965 to 1970 and traveled up and down the mountain daily. If you are interested in what went on up there, drop me a line. I am really interested in hearing more about the hang gliders,

I also grew up just north of the punch bowl and would love to know a little more about the site. Im particularly interested in figuring out how I could visit it, whether possible. I can see it out the front window at my folks and just now realized the Internet might have a few tidbits. Thanks for what youve provided here. Anything else you can provide is appreciated.

I have lived here for more than 30 years I am quite intrigued as I believe there is much more to it than what meets the eye. I have always been told that’s the “fire tower” or water tower as many residents of the town still are unaware of the actual specifics of the site. I would be most interested in learning more about cannonball

I grew up in Mercersburg and in the early 90s a few friends of mine and I used to rappel off of Cannonball. It disturbed me then that people were destroying it. As far as I knew the Ernst family owned the property then and we had permission to do what we were doing. From what I understand now, it is part of a hunting camp or something of the sort.

I live on the Little Cove side of the mountian where Cannonball is located. I was wondering what all went on up there. Im just trying to find some facts out on it. Ive been able to see it and visit it all my life and have always wondered. Please get back with me, I would love to hear from you John Cross.

I hope that you receive my e-mail address just send me some questions and I will be glad to answer them.

Tyler,

where about in the little cove area are you? We’ve got a hunting camp right by the power line (gas line?). We’ve been trying to get to the bottom of this mystery for a long time. As Mr. Cross mentioned everyone in the area thinks it’s a water/fire tower. In the last couple of years when the AT&T towers went up I decided to do a little research. I came across sites that said there was some suspicion that the Cannonball tower was a presidential underground bunker, and that the “ATT towers” are that as well. Does anyone know whether this new ATT location could be our modern day Cannonball?

Tyler, I grew up just north of the punch bowl and would love to visit this place. Did you know the land owners? I can see it out the front window at my folks. Wondered if thered be any opportunity to do so.

Sorry I did not receive your e-mail, I’m not sure what happened there. Maybe you can try it again.

I was wondering if you could get me a better look at this tower. I have seen it for years and curiosity is getting to me. please email me back at rvanm2@verizon.net thank you so very kindly

johncross910@sbcglobal.net

There is alot of historic cold war sites in the Washington, Metropolitan area. Does anyone know what the facility was in Smithsburg, MD at Federal Lookout Road. Looks like it may have been some type of communications facility and there currently is a large geodesic dome covering something at that location

The dome covers a drinking water supply.

Looking back at historic imagery, the dome wasn’t always there but the large concrete pad was. It looks like it may have been a Federal facility at one time in it’s past. Don’t know if it was related to the other Cold War sites or just a county utility facility.

It was always just Smithsburg’s water storage. It was concrete vaults before and now it’s covered and expanded to include above ground for added capacity.

Yes, I was there too. Right out of Microwave school and K06 school at Ft Monmouth and then also at the Navel Security Group for training in voice security (KY1) and two years at the White House (including Crystal) and then COMZREAR for three years and two years with the Chiefs of Staff in the War Room and other locations, mostly TDY, etc. Contact me – epsilon@inyourface.info

President Eisenhower had a bunker assigned to him in the Manzano Weapons Storage Area southeast of Albuquerque on what was called Manzano Base. The facility has been closed since the early nineties. I believe Channel 13 KQRE? had a report on the facility many years ago, maybe even a tour of the command post as abandoned. It would be interesting to learn of the communications to the bunker and a little more history. I do not believe the President ever visited the command post. Undoubtedly there are a few comm types still surviving to add to this bit of history.

Martin, I’m from the Albuquerque area at the moment, my grandpa worked for LASL Z-Section, which became Sandia and my dad was a Trident tech.

From my own digging, I’ve learned a lot about the Manzano Base and the others (the current Kirtland Coathanger, Lake Mead Base, Killeen Base, Bossier Base, Kitsap, Kings Bay, etc). Yes at one point there was a Presidential bunker in Manzano, no it was never used and from what I can gather, it was converted to one of the Type B or D storage bunkers.

A lot of the bunkers at Manzano are still in use for storing explosive mixed waste, and other things, but there’s something else going on at Manzano itself. The parking lots are way too busy for it to be disused. The mountain does belong to the Air Force Research Laboratory’s Space Vehicles and Directed Energy Weapons directorate (used to be called the Phillips Lab) now so they’re likely doing something with it. The cars that are parked there aren’t for Lovelace Respiratory Research Institute.

If KRQE or KOB were shown anywhere it was probably the S-Building or maybe Plants 3 or 4. The way that plants 1 and 2 are set up is way too much like Site R and Mount Weather to show the media. Thing about Plants 3 and 4 is that some of the equipment is similar to the KUMSMC which is also something that isn’t discussed so I doubt they’d show anyone them either.

I will say something’s up out on the Mesa near Rio Rancho Estates, but the SandCo and RR cops show up so fast that I’ve yet to get an idea of what. I have a feeling its related to continuity but in regard to communications. I’ve stumbled upon facilities like that in Florida before with about the same reaction.

Frank, in 2018, the same year you posted this, I know of someone who worked in a deep underground facility under Plant 2. The work was not directly related to the enduring stockpile, but was a deep underground aircraft storage facility, filled with advanced aircraft that publicly are not known to exist. How the aircraft get to and from the facility to a runway is open to speculation, but I now believe I know how.

Check out the rectangular light blue building across the road from Plant 2 entrance on Google Earth, with construction vehicles in the parking lot. A freight elevator in that building is a 5 minute elevator ride to deep under the mountain.

Orient that building’s walls on Google earth and it points in the same direction as the underground facility. It points to a second building on the west fence line of Manzano. Orient Google Earth to that second building and it points directly at the former Boeing Airborne Laser hangar, the closest aircraft hangar to Manzano. This hangar is about 800 feet lower in elevation than the blue roof building near Plant 2 on the east side of Manzano. A 5 minute freight elevator ride is about 800 feet. Picture an aircraft elevator like on a USN carrier, but inside the Boeing hangar.

A special thanks to all contributors, who have shared this intense amount of information, that has literally propelled my obsession into researching and documenting the various communication networks.

Would love to talk more with author of blog and other people who have shared information about AT&T Hardened & WHCA Cold War Networks..

s3200xl@optonline.net (Michael)

I am also a information person who keep up on AT&T Hardened & WHCA Cold War Networks.

I like to share information on this subject. most information that I have is on google earth.

i’d love to hear what you know.

Any idea what they’ve done at Site D – Damascus lately. They’ve added a separate tower with some type of radar and a radome on the existing tower.

This is about cartwheel in tenleytown Washington, D.C. There is a bunker type home located on belt road nw right across the road from cartwheel. I always suspected that this house serves some kind of support for cartwheel.

I was stationed at Cartwheel from March, 1964 until February, 1969 and to my knowlegee, a support house did not exist during those years.

I live in Mercersburg, PA, and the tower is visible with only the naked eye from my house. I always thought it was some sort of a communications tower for the government because of rumors and such. No my hunch is proven

There is a concrete structure on the mountain West a Carlisle Pa. That has conical Micro-wave rec/ transmiters on. A very odd and solid structure. Any ideas?

i know of a presidential bunker in baltimore county maryland that i believe has never been disclosed located at Glen L. Martins number two plant

fyi, for those interested in Cartwheel, there has been quite a bit of recent construction and presumably repurposing activity at the site over the past handful of years. You can see it through time lapse aerials. You can also see the current look very clearly in Google street view. The FAA or whoever clearly has a good number of computer servers in there now – there is a new barn-like structure built adjacent to the tower, connected by a new enclosed passageway, which has large vents of the type you would have for a large data center. New barbed wire fence perimeter is in place, along with a very fancy looking electronic and secure entry/exit set-up. MUCH more overtly secure than it used to be. I live just a mile or so away.

It is my understanding that Cannonball was not removed due to issues about who owns parts of the property and access road.

Anyone familiar with Site C?

Anyone familiar with site C, the comms facility in Cascade MD atop the mountain? Large tower, building, and lots of armed MDEPD and Army folks. Even the tower owners on the other sites up there have to be cleared for access every time they go up.

I attended Mercersburg Academy in the mid seventies. The locals turned us on to cannonball for a great place to party and explore simultaneously. As word got out of abandonment , vandals found it and it was sad. They stripped the place of a lot of copper wire. I remember a helicopter landing pad,a shower,possible decontamination room at the entrance,spring loaded floors,and a out building next to it.