I recently participated in a Society for Industrial Archeology online program featuring projects with a social justice element. The SIA program titled, “Infrastructure and Social Justice” included a presentation on a Tennessee bridge used during the Trail of Tears and a viaduct in Erie, Pennsylvania.

Infrastructure and racial segregation have a long and fraught history. Railroads and highways frequently created firm boundaries separating racialized spaces. Many cities throughout North America have their “other side of the tracks” or interstate highways that were built to separate Black neighborhoods from white ones. In some places, like Detroit, Michigan; Decatur, Georgia; and, North Brentwood, Maryland, walls and other barricades divided Black space from white space.

Railroad tracks, Decatur, Georgia.

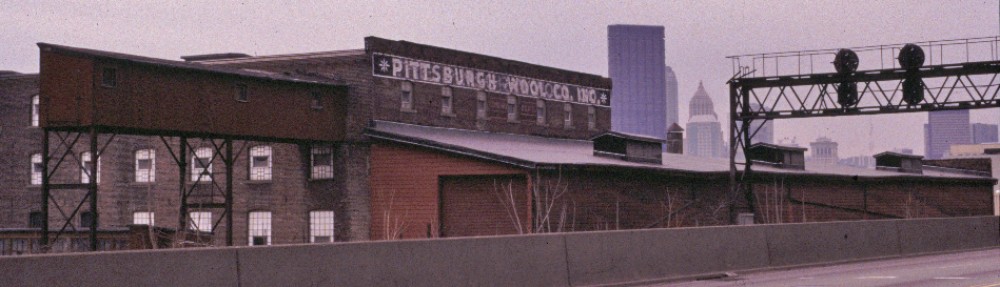

Interstate 279, Pittsburgh’s North Side.

Birwood Wall, Detroit, Michigan. Library of Congress photos.

Wall, Decatur, Georgia.

Windom Road barrier separating North Brentwood from Brentwood in Prince George’s County, Maryland.

And, there is a long history of infrastructure being weaponized to destroy Black communities by constructing rights-of-way through them, destroying homes, businesses, and churches; introducing visual, auditory, and particulate pollution; and, disrupting vital pedestrian and vehicular traffic networks.

Africville, Halifax, Nova Scotia. Photo by Bob Brooks, Nova Scotia Archives, negative sheet 8a image 20.

Sometimes infrastructure mediated segregated spaces. Bridges, like the Talbot Avenue Bridge in Silver Spring, Maryland, created essential connections between historically white and Black communities. For the remainder of this brief presentation I am going to talk about the Talbot Avenue Bridge’s history as a common transportation structure that connected historically Black Lyttonsville with the Silver Spring sundown suburb.

What distinguishes the Talbot Avenue Bridge from other engineering structures in racialized spaces is that historic preservation efforts over three decades failed to recognize the bridge’s place in social history and the attachment to it by Lyttonsville’s residents.

Though the bridge was demolished in 2019, grassroots preservation and commemorative efforts developed during its final three years led to a greater understanding of Silver Spring’s segregationist history and to the bridge being documented by the Historic American Engineering Record prior to its removal. These were extraordinary examples of community-driven mitigation in cases where official efforts to mitigate the adverse effects of transportation projects to historic buildings and structures fall short.

The Talbot Avenue Bridge was a recycled and inverted railroad turntable. The turntable appears to have been fabricated based on a design originally patented in 1887. Railroads regularly recycled stock, including turntables and cars, into bridges.

Turntable patent.

In 1918, the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad moved the turntable from the company’s Martinsburg, West Virginia, shops to its Georgetown Junction, the place where the Georgetown Branch met the Metropolitan Branch just north of Washington, D.C.

The turntable replaced an earlier wood truss bridge that had been built around 1904. It originally carried an unnamed two-land roadway over the railroad tracks. Over the years, the bridge had several official and informal names: Bridge 9A, the Hanover Street Bridge, and the Talbot Avenue Bridge; many Lyttonsville residents simply called it “The Bridge.”

B&O Railroad engineering drawing showing the design for a new bridge and the existing bridge (highlighted).

Samuel Lytton, a free African American, first settled in the community to the west of the bridge in 1854 when he bought a four-acre farm. By the time Lytton died in 1893, the community had grown into a thriving rural hamlet with a school, store, churches, and homes. Lytton’s family lost his property in foreclosure two years after he died. The white Washington attorney who bought the land subdivided it and called it “Littonville.”

“Littonville.” Montgomery County Land Records, Plat Book 1, Plat 36.

White Montgomery County residents began calling the space Linden. Lyttonsville became one of several dozen Montgomery County rural hamlets founded by African Americans before the Civil War and during Reconstruction. The communities closest to the District of Columbia border forged closed relationships with their counterparts inside the District. Collectively, they formed an extended borderlands community characterized by kinship ties, business and social relationships, and church affiliations.

Like its counterparts throughout North America, Lyttonsville became a rural ghetto with no paved streets, no running water or sewer, and with nuisances closing in on its borders. The B&O railroad condemned part of Samuel Lytton’s farm in 1892 to build the Georgetown Branch.

B&O Railroad condemnation of Samuel Lytton’s land, 1891.

In the 1940s, Montgomery County opened one of its two trash incinerators at a site within the community. Also in the 1940s, radio broadcasters began building transmitters with tall antenna towers. Cumulatively, Lyttonsville experienced environmental racism on multiple fronts.

Radio broadcast tower, Lyttonsville, 2019.

Meanwhile, across the tracks, starting in the years bracketing the turn of the twentieth century, residential subdivisions began appearing near an 1850s plantation founded by Francis Preston Blair. For much of the late nineteenth century, the area had been known as Sligo. Blair’s descendants who made their fortunes in real estate speculation in the second decade of the twentieth century branded the unincorporated community Silver Spring after the plantation.

Silver Spring developed as a sundown suburb, a place where racially restrictive deed covenants kept them from buying and renting homes. Jim Crow segregation prevented Blacks from patronizing many of the businesses in the growing suburb. For much of the twentieth century, the few African Americans who lived in Silver Spring were domestic servants: maids, gardeners, and chauffeurs. Racially restricted deed covenants and later redlining enforced that segregation.

Silver Spring remained rigidly segregated until the late 1960s. Responding to external pressures, including federal agencies moving large Black workforces to places like Silver Spring and Rockville, the county seat, and to increased civil rights activism, Montgomery County passed a series of laws gradually outlawing discrimination in public accommodations and in housing. Even as late as 1967, many Silver Spring residents boasted that one of the community’s best attributes was its lack of Black residents.

As Montgomery County enacted laws prohibiting discrimination based on race, the county also moved forward with an ambitious urban renewal program designed to eliminate what it called blighted housing and to improve economically distressed urban neighborhoods and rural hamlets. Most of the places Montgomery County targeted were historically Black communities like Lyttonsville, which the county determined was one of the highest priority areas for redevelopment.

To white Montgomery County leaders and residents, Lyttonsville was blighted and stigmatized.

Stigmatized sites are an industrial archeology staple. We study tanneries, paper mills, and chemical plants that polluted the air, water, and earth. The sites and people associated with them frequently were stigmatized: discredited, marginalized, and collectively devalued.

Urban renewal booklet published by the City of Decatur, Georgia.

Stigmatization makes it easy to erase the sites and people through “clean-ups,” “renewals,” and “revitalizations.”

Page from Decatur urban renewal booklet.

The Talbot Avenue Bridge case offers us an opportunity to explore stigmatization through a different lens: multiple layers of stigmatization, from the stigmatized spaces and people of Lyttonsville to the stigmatized artifact, the bridge itself, and the divergent responses to its impending demolition in 2019. This stigmatization is fully illustrated in the graffiti that appeared on the bridge in 2016 or 2017: bold letters spelling out the word “JUNK.”

Historic American Engineering Record photo of the Talbot Avenue Bridge by Jarob Ortiz.

And that graffiti stung lifelong Lyttonsville residents. As planners were completing work on the 2018 centennial celebration, one objected to using photos of the bridge taken after the graffiti appeared: “I just pulled up the final version of the program and want to ask why we have the picture of the bridge there that says “junk?” She later wrote, “If we could have a replacement, it would be much better.

The graffiti reproduced the ways that Montgomery County neglected the bridge and allowed it to deteriorate. Since the 1980s, the bridge had been closed multiple times for emergency repairs. Residents on both sides of the bridge hotly contested those closures. Lyttonsville residents wanted the bridge reopened while North Woodside residents lobbied to have it permanently closed.

The Montgomery Times, Sept. 15, 1996.

Instead of steady maintenance or a comprehensive rehabilitation program, Montgomery County leaders essentially allowed the bridge to rust and rot. In historic preservation, that’s known as “demolition by neglect.”

Rusted bent, Talbot Avenue Bridge, 2018.

Historic preservation evaluations consistently focused on the bridge as an engineering artifact and its associations with the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. Regulatory studies done to comply with the National Historic Preservation Act and National Historic Preservation Act agreed with earlier evaluations that the bridge was eligible for listing in the National Register of Historic Places for these reasons. To resolve the adverse effects to the bridge by its demolition to build the Purple Line, a new light rail commuter line, historic preservation consultants agreed to complete a new Maryland Inventory of Historic Properties form.

Completed Maryland Inventory of Historic Properties Form. This document represents the only mitigation by the State of Maryland for demolishing the Talbot Avenue Bridge.

Meanwhile, as these studies were winding down, residents in the communities on both sides of the tracks began collaborating on ways to commemorate the bridge. They asked county and state officials for alternatives to simply demolishing the structure.

Their efforts yielded a promise by Montgomery County officials to relocate the turntable center span to a nearby park. Local and national journalists made the mistake of describing this promise as “saving” the bridge.

Proposed relocation site (highlighted) for the Talbot Avenue Bridge center span.

Finally, the collaborations among the neighborhoods resulted in several community commemorative events, including a celebration marking the bridge’s one-hundredth birthday, a lantern walk, and a candlelight vigil. To ensure documentation commensurate with the bridge’s historical significance, in early 2019, a Historic American Engineering Record team independently documented the bridge.

Historic American Engineering Record team documenting the Talbot Avenue Bridge, February 2019. Pictured left-to-right: architect Christoper Marston and photographers Todd Croteau, and Jarob Ortiz. Photo by historian David Rotenstein.

The grassroots mitigation efforts forged new bonds among neighborhoods once divided by race and racism. At the 2018 centennial celebration, the president of the civic association in the historically white North Woodside neighborhood became emotional as he read a proclamation passed by his organization renouncing the racial restrictive covenants once placed on the properties there.

Collectively, the commemorative activities and collaborations transformed the Talbot Avenue Bridge from contested space mediating the break between historically Black and white spaces into a space for reflection, reconciliation, and repair. The connections made before the bridge was demolished endured into the pandemic as the neighborhoods worked to mutually assist each other in response to the public health and economic crisis.

The historic Talbot Avenue bridge is lifted from its place after more than 100 years on July 5, 2019. Photo: Jay Mallin jay@jaymallinphotos.com

The Talbot Avenue Bridge is a remarkable example illustrating the potential to expand the ways in which we understand historic infrastructure and the approaches we take to preserving it.

© 2020 D.S. Rotenstein

Shortlink for this post: https://wp.me/p1bnGQ-3BM