I have been interested in concealed telecommunications sites since I first began working on regulatory compliance for Federal Communications Commission (FCC) licensees struggling to understand the complexities of Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act. This is the first of a series of posts on concealed telecommunications infrastructure and the American landscape.

Category Archives: History

Philly Folk Festival Season

Each summer Google directs dozens of visitors looking for information on the history of the annual Philadelphia Folk Festival. This year’s festival runs from August 20 through the 21st and the hits to my site are already picking up. Why is Google sending folks to my Web site? Because in the 1990s I covered folk music for the Philadelphia Inquirer and in advance of the 1992 festival I wrote a Sunday feature on the festival’s history and the folks behind it: The Philadelphia Folksong Society. I was finishing up my coursework at Penn at the time and I just happened to be enrolled in the now-defunct doctoral program in Folklore and Folklife. I also happened to be gearing up for the required FOLK 606: History of Folklore Studies class taught by the inimitable Dan Ben-Amos and I decided to use some of the reporting I did for the Inquirer article for one of my class papers. Since my time at Penn coincided with my early years writing about music I got to use interviews with folks like BB King and others as source material for term papers. Now that was cool.

For the Folk Festival story (and subsequent paper) I interviewed legendary Philly radio personality Gene Shay and many of the festival’s founders. I also interviewed Irish musician (and fellow Penn folklorist) Mick Moloney as well as George Britton (who died recently). Britton was a fun interview. Near the end of our interview he sang the chorus of a tune he wrote about the festival. He called the song, “Barefoot, Bearded and Bedraggled”:

I’m barefoot, bearded and bedraggled

Stoned and drunk as I can be

I’m the counterculture and I’m all folked up

This here’s my cry of liberty. Continue reading

Civil Defense

What would you do if you were sitting at the dinner table and a loud buzzer went off to inform you that the federal government had detected inbound nuclear missiles? Back in the late 1950s and early 1960s the government market-tested and field tested the National Emergency Alarm Repeater device to provide just such a warning.

The Undisclosed Location Disclosed: Continuity of Government Sites as Recent Past Resources

By David S. Rotenstein

[08/22/2011: Update: Read the follow-up post on newly identified photos showing the construction of the Fort Reno “Cartwheel” facility in Washington, DC]

In 2004 the State of Maryland was both project proponent and regulatory reviewer in the Section 106 consultations tied to the construction of a proposed telecommunications tower at Lamb’s Knoll, a mountaintop ridge that straddles Washington and Frederick counties west of Frederick. A Federal Communications Commission licensee, the State was required to identify historic properties, evaluate their significance under the National Register Criteria for Evaluation, and determine whether the proposed project would adversely affect properties listed in or eligible for listing in the National Register of Historic Places. Properties likely affected at Lamb’s Knoll included the Appalachian Trail, a 1920s fire observation tower turned telecommunications tower, and a Cold War-era army facility.

Maryland’s agency for emergency telecommunications infrastructure retained a cultural resource management firm to conduct the Section 106 compliance studies. The firm’s initial 2003 report noted the presence of nearby nineteenth century farmsteads and surrounding Civil War battle sites, but there was no mention of the twentieth century resources.[1] The Maryland Historical Trust (the state historic preservation office) reviewed the 2003 report and concurred with its authors that no historic properties would be affected by construction of the proposed tower. Located less than 500 feet from the proposed tower site and rising approximately 100 feet above the mountaintop, the former Cold War facility was notably absent from all discussions turning on historic preservation and the proposed tower. Hidden in plain sight and visible from miles around, the Lamb’s Knoll facility is one of a handful of continuity of government sites built in Maryland, Pennsylvania, Virginia, West Virginia, and Washington, D.C., that were designed to house large numbers of federal officials in underground bunkers while the exposed concrete towers that housed sophisticated radio equipment kept communications open among the survivors, the military, and civilian populations.

This article stems from my involvement in that 2004 project. I was retained by a coalition of environmental groups including the Harpers Ferry Conservancy and the National Trust for Historic Preservation to evaluate the historic properties the groups believed that the State’s consultant failed to identify in the initial round of Section 106 consultation. Between 2001 and 2008 I did many Section 106 projects for FCC licensees and I had been working on histories of postwar telecommunications networks.[2] By the time I had been brought into the Lamb’s Knoll project I was sensitive to the historical significance embodied in telecommunications facilities like the repurposed fire lookout tower and the Cold War facility.

Unbuilding Trades

A Levitt Encounter

Architectural and cultural historians for decades have been tuned into the significance of the sprawling Postwar suburbs built by Levitt & Sons bearing the family firm’s name. Recent research into other Levitt developments like Belair in Bowie in the Washington, D.C., suburbs has expanded our understanding of the Levitts’ impact on modern cultural landscapes and in shaping American homeownership. Last week while doing some fieldwork in the Philadelphia suburbs I encountered a 1960s subdivision planned by firm president William J. Levitt (1907-1994).

Architectural and cultural historians for decades have been tuned into the significance of the sprawling Postwar suburbs built by Levitt & Sons bearing the family firm’s name. Recent research into other Levitt developments like Belair in Bowie in the Washington, D.C., suburbs has expanded our understanding of the Levitts’ impact on modern cultural landscapes and in shaping American homeownership. Last week while doing some fieldwork in the Philadelphia suburbs I encountered a 1960s subdivision planned by firm president William J. Levitt (1907-1994).

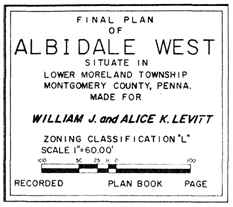

Named Albidale — Al (for Alice K. Levitt) and bi (for Bill Levitt) plus the rustic-sounding dale — the development included two tracts culled from a large 600-acre horse farm and steeplechase track assembled by Philadelphia philanthropist George W. Elkins (1886-1954) begun in the 1920s. Albidale’s core, dubbed Albidale West by Levitt, includes a cluster of stone homes Elkins built in 1936 for his employees and a pair of eighteenth century stone houses that once were part of farms Elkins bought in the 1920s and 1930s for his expansive Justa Farm complex.

Albidale West Plat. Montgomery County Land Records.

Earlier this year a new book on Pennsylvania’s Levittown, Second Suburb, was published and I have now moved my copy to the top of my reading list. The Levitts were fresh in my mind before I did last week’s fieldwork because I had just read Jamie Jacobs’ chapter on Belair in Richard Longstreth’s new book, Housing Washington. Jacobs’ 2005 dissertation has a valuable discussion of suburban real estate marketing techniques that I am using in my work on Silver Spring’s 1939 World’s Fair Home. Two things intrigue me about Levitt and they are beyond the scope of my current research project: 1) Levitt did not scrape away all evidence of the 18th, 19th, and early 20th centuries to make way for his development; and, 2) Levitt and his wife briefly lived in one of the Elkins houses. Continue reading

Video: Housing the Homeless in Washington

Earlier this spring I did a video for a client’s online annual report. The video — really a compilation of photos and interviews with a narration track — has been posted to the their YouTube channel. This was an exciting project because I got to use my ethnographer’s toolkit to tell a great story. The focus of the video is how organizations in Washington create supportive housing for the city’s homeless. Supportive housing programs provide chronically homeless people with a safe and affordable place to live along with access to services to help them get jobs, counseling, and other things necessary to re-integrate them into society. I met and photographed several formerly homeless women in one of Washington’s supportive housing apartment buildings and then I went to photograph homeless camps under Georgetown bridges. One woman who did not want to be photographed told me why the bridges were safer than homeless shelters and storefronts. Another woman proudly showed me around her apartment while explaining why she was reading Bill Gates’s book, Business @ the Speed of Thought. I would never have predicted ten years ago that I would be documenting Washington’s homeless people and the programs meant to help them.

Interchangeable Parts: 10 Years Later

Last week I attended the Vernacular Architecture Forum conference in Washington. Conferences are great events that give consultants (like yours truly) a chance to speak with colleagues from around the country. At the banquet I had a long conversation with someone who does cultural resource management work out in the Pacific time zone. We commiserated about the ranks of CRM firms who send out archaeological technicians to identify historic buildings and landscapes. We lamented the lack of regulatory oversight by federal agencies and state historic preservation offices to ensure that historical research and analysis were being done by historians and not archaeologists being kept billable by mega consulting firms.

Our exchange brought to mind similar conversations I had carried out with the late Ned Heite. Some of these took place on email lists like ACRA-L. One memorable one took place in June 2000. Ned aptly titled it “Interchangeable parts. Ned had responded to one of my posts, which read in part:

As I sit here looking through yet another Section 106 report on above-ground architectural resources prepared by archaeologists and rejected by a SHPO, I wonder when anyone in this industry is going to understand the “American System.” Interchangeable parts are things that are bulk or mass-produced that can be swapped out for in-kind identical parts in a tool, machine, whatever. If you’re going to apply the interchangeable parts model to the CRM industry, swap parts in offices, jobs, etc. with like parts. Don’t send archaeologists out to do what an architectural historian should do. After all, when your brakes go on your car, you’re not goign going to replace them with spark plugs, now are you?

Ned’s post read:

Bravo, David. As one who is “certified” by the SHPO in all the disciplines, I second your statement. By coincidence of employment, I have managed to push all the buttons for the Secretary’s standards. This does not, of course, mean that I know what I am doing.

Along those same lines, one of my pet peeves is the portable historian. When the weather turns bad, the state archives are flooded with field techs and others, who are supposed to be doing historical background research. Most of them haven’t the foggiest notion of historical research or the history of the locality.

Local history research is an arcane field, best left to people who are specialists in a very narrow geographical area. Yet CRM firms routinely dispatch unqualified staff to research the background history of places they can’t even pronounce!

The standards should be tightened, exponentially, and the historical background should be mandated to be done by a person with local expertise, who is also recognized as a competent CRM historian. And remember that a CRM historian is a very different creature from a kid with a fresh MA in some kind of generalized history.

Little has changed in the 10 years since that exchange. Large engineering companies with cultural resource management divisions continue to deploy teams of archaeologists to do historians’ work. I recall observing the archaeologists return from the field and in mixed horror and amusement watched them spend countless hours (and clients’ dollars) trying to match fuzzy photos of buildings with what they could find in Virginia and Lee MacAlester’s generic Field Guide to American Houses.

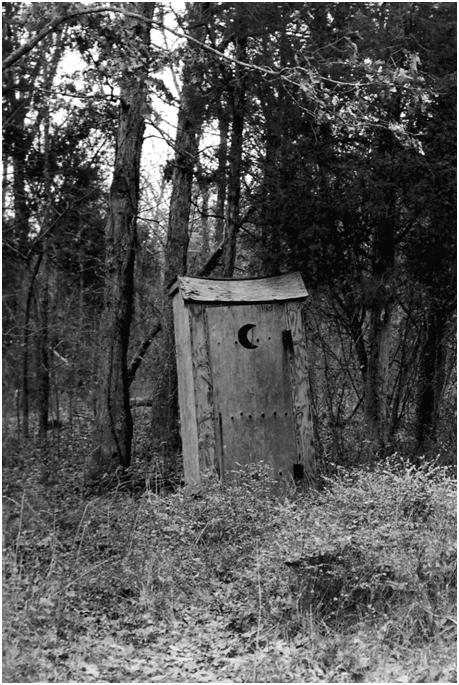

I still have the wonderful photo of a Prince William County privy that one archaeologist (who did not do the fieldwork, but who was given a stack of photos to describe) characterized in her report as a “desk.”

History in the crapper: one archaeologist’s “desk.”

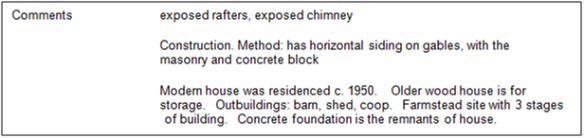

Among some of the choice architectural descriptions penned by archaeologists are these:

Silver Spring and a “Socialized Medicine” Sidebar (Part I)

Shall Government Help Pay Nation’s Doctor Bills? Sharp Fight Aroused by Program.

This headline could have appeared in any of the nation’s papers in 2009 or 2010. Instead, it was published in San Jose, California, in August 1938. That year one of the country’s first managed health care entities, Group Health Association, Inc., went head to head with the American Medical Association and the District of Columbia medical establishment in a legal battle over patients’ rights and affordable health care for low-income families.

Dr. Mario Scandiffio (1902-1996), a Washington pediatrician employed by GHA, found himself in the center of the imbroglio when his hospital privileges were revoked along with those of other GHA practitioners. My research frequently veers off into unanticipated territory and last year’s encounter with Scandiffio and his wife, Pauline (1903-1989), is becoming one of those side trips. The Scandiffios were the first owners of Northwood Park’s 1939 New York World’s Fair Home, the subject of my paper at this year’s Vernacular Architecture Forum conference.

Dr. Mario Scandiffio (1902-1996), a Washington pediatrician employed by GHA, found himself in the center of the imbroglio when his hospital privileges were revoked along with those of other GHA practitioners. My research frequently veers off into unanticipated territory and last year’s encounter with Scandiffio and his wife, Pauline (1903-1989), is becoming one of those side trips. The Scandiffios were the first owners of Northwood Park’s 1939 New York World’s Fair Home, the subject of my paper at this year’s Vernacular Architecture Forum conference.

GHA was founded in 1937. This was a time during which the American health insurance industry was an emerging business. The model was simple: a monthly premium payment bought access to a network of specialists and generalists and hospitalization plus necessary diagnostic tests. The idea for founding GHA grew from discussions by managers in the Home Owners Loan Corporation, a part of the Federal Home Loan Bank Board. By attempting to minimize absenteeism and other costs associated with employee illnesses while also improving the quality of those peoples’ lives. According to a 1941 article by Dr. Scandiffio, GHA sought to eliminate the economic barriers separating the poor and access to healthcare and make practicing medicine more efficient by sharing lab and x-ray facilities in a large urban clinic. The AMA perceived GHA as a threat and moved aggressively against the new medical cooperative which was being accused of trying to socialize medicine. The medical establishment, i.e., the AMA and the District of Columbia’s District Medical Society, swiftly began marginalizing GHA’s physicians by revoking their hospital privileges and memberships.

This being Washington, D.C., legal action was quick in coming. The Justice Department opened an investigation into the AMA and the Medical Society of the District of Columbia for violating antitrust laws. Indictments followed and the case wound its way through the federal courts until 1943 when the U.S. Supreme Court issued an opinion upholding the lower courts’ decision that the AMA and Medical Society had acted unlawfully.

Dr. Scandiffio was one of GHA’s first medical professionals. The son of Italian immigrants to New York City, Mario V. Scandiffio graduated from The George Washington University medical school in 1928 and did his residency and internship at the New York Post Graduate School. Scandiffio’s medical school roommate introduced him to Pauline Loria, a Bureau of Engraving employee and singer with her own show on local radio station WOL. Married in 1930, the Scandiffios lived in Washington where he worked in private practice. Dr. Scandiffio’s first day of work for GHA was November 1, 1937, the day GHA’s Eye Street clinic opened to the public.

One day after starting work at GHA Dr. Scandiffio received a registered letter from the District of Columbia Medical Society directing him to appear before the group’s Compensation, Contract and Industrial Medicine Committee to answer charges that he had engaged in unprofessional conduct by practicing for GHA. Scandiffio responded by first resigning from the Society and then rescinding his resignation. The Society expelled Scandiffio in early 1938 and the case began attracting national attention. The AMA opposed GHA because the new model threatened the institutional framework of professional medicine. The struggles to reform healthcare in the United States in 1994 and again when President Barack Obama took office look remarkably similar to the issues faced by GHA and Dr. Scandiffio. In his 1941 paper on the GHA, Dr. Scandiffio described GHA’s most fundamental beliefs:

It was felt that there should be little or no economic barrier to securing competent and adequate medical care. All of us are gamblers at heart and, unfortunately, one of our most vital possessions – good health – is too often gambled with. It is almost a universal characteristic to delay seeing the doctor until all other means at our disposal have failed. The result is that the private practitioner sees only advanced illness and has little time for the care of early illness or for preventive medical care. Care of early illness and preventive care are, to me, the primary advantages of prepaid group medicine for it is distinctly to the best interests of both patient and physician to know how to achieve good health and how to maintain it. Then too, early care results in lower morbidity and mortality and in a marked reduction in the number of serious or advanced illnesses. [1]

Scandiffio resisted the medical establishment’s pressures and remained with GHA. In the spring of 1939 he became GHA’s medical director and a few months later he and his wife bought Northwood Park’s 1939 World’s Fair Home. Scandiffio left GHA in May 1944 and opened his own Silver Spring practice on Georgia Avenue. The Scandiffios lived in Silver Spring until 1952 when they moved to Miami, Florida.

Note

[1] Dr. Mario Scandiffio, “The Program of the D.C. Group Health Association,” Social Security in 1941, 145-149.

Look for Part II: a closer look at Group Health Association, Inc.

Thanks to Ann Scandiffio for sharing her family photos.

© 2010 David S. Rotenstein

Who was Col. Lyde Griffith and Why Preserve His MoCo Farm?

The Col. Lyde Griffith Farm (M: 15/27), also known as the Mehrle Warfield Farm, is located at 7301-7307 Damascus Road in Gaithersburg. The current property covers approximately 87.6 acres north of Damascus Road and northwest of Etchison, a rural unincorporated hamlet.[1] The farmstead includes several domestic and agricultural buildings, agricultural fields, and areas in mixed hardwoods. At its March 10, 2010, work session the Historic Preservation Commission voted unanimously to remove the property from the Locational Atlas and Index of Historic Sites and to not recommend designation in the Master Plan for Historic Preservation.

I agree with the HPC’s decision and the reasons stated by individual members for voting against designation. The documentation prepared by staff in support of its recommendation of designation based on the property’s historical associations and architecture was not defensible nor was it accurate and complete. If the HPC had voted to designate the property, all 87.61 acres and individual buildings would have been subject to regulation by the HPC. This brief summary of the property’s history and cultural features derives from research conducted at the Library of Congress. The information presented below underscores the serious questions raised by the HPC regarding the research conducted to support the proposed Upper Patuxent Area Resources Amendment to the Montgomery County Master Plan for Historic Preservation.

Audio (heavily compressed MP3) from the March 10, 2010, work session where the HPC discussed and voted on this property is available here.

Architecture

According to the December 2009 MIHP form completed by staff, the surviving historic house is a “log and frame structure with a three bay, side gable main block.”[2] Staff noted a metal-clad roof, synthetic siding, a rebuilt [brick] chimney, and an attached garage. Most of staff’s description of the property derived from a 1987 survey. At the March 2010 work session staff was unable to answer HPC members’ questions about the house’s integrity nor could staff provide the HPC with a definitive construction date for the building.

Staff wrote in the 2009 MIHP form, “The log and frame house was likely built between 1797, the date of Col [sic] Lyde Griffith’s first marriage to Anne Poole Dorsey and 1809 … The three bay house is a traditional form that was used throughout the region in this era.”[3] Pictures of the home included in the 2009 MIHP form, along with earlier MIHP forms, suggest that the house is a traditional I-house, a common nineteenth and early twentieth century vernacular house type found throughout the eastern United States.[4] The building shown in the photos has a pair of internal gable-end chimneys, a 1.5-story gable roof side (east) addition and a one-story shed roof addition, and a one-story hip-roof garage attached to the building’s rear (north). There are two first-floor windows piercing the west (side) façade. These windows appear to be 1/1 double-hung-sash replacement windows (metal or vinyl). The original three-bay principal façade (south) appears to have a one-story shed roof porch support by wood posts. A photo included in the 2009 MIHP form taken from a distance shows 6/6 DHS windows with wood shutters.

In her report delivered to the HPC at the March 2010 work session planner Sandra Youla described her visit to the property. “We were invited off of the site when we were there so this is the best we can do for you,” reported Youla as she delivered her presentation to the HPC. Youla explained that her departure from the property precluded collecting additional information to present to the HPC.

The dairy barn complex was described at length in the 1987 survey by Andrea Rebeck and in the 2009 MIHP form. In addition to the nineteenth and early twentieth century buildings and structures, there are several late twentieth and early twenty-first century buildings located at this property. These include a large new residence and agricultural buildings and structures related to the active dairy farm.

Landscape

Staff recommended an environmental setting that embraces the entire parcel: “The setting is 87.61 acres, being parcel P909. In the event of subdivision, the features to be preserved include the historic dwelling house, the dairy barn, the Griffith family cemetery, and the vista from Damascus Road.”[5] Staff’s recommendation did not include potential archaeological resources, including the antebellum chrome mines reported to have been operated on Lyde Griffith’s farm.

Historical Significance

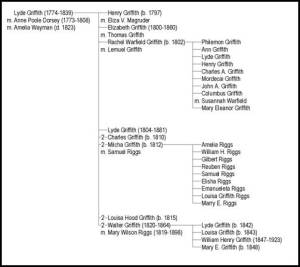

Lyde Griffith (1774-1839) was born into a prominent Maryland family. Engaged in state and local government, large landholders, and military officers in the late Colonial and early Republic periods, the Griffith family’s role in the development of Maryland history is documented in several local histories and genealogies.[6] Lyde Griffith’s father, Samuel, was a Continental Army captain and farmer. Lyde was the only child born to Samuel and his first wife, Rachel Warfield. Lyde Griffith’s first wife, Anne Dorsey, with whom he had three children, died in 1808; he later married Amelia Wayman and they had four children. The Griffith genealogy is complex and warrants further research to tie specific Montgomery County farmsteads to individual descendants and affines in the Warfield and Dorsey families.

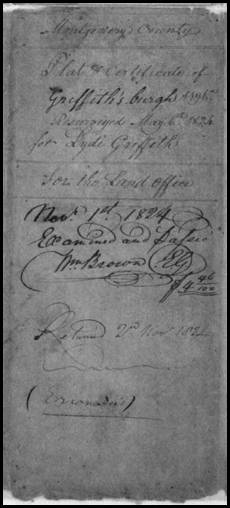

Despite Historic Preservation Office staff’s assertions in earlier documents and testimony that the source of Griffith’s title, “Colonel,” was unknown, several histories identify Lyde Griffith as a captain who served in the 44th Regiment (Montgomery County) during the War of 1812.[7] The Griffiths held extensive lands and relied on African-American labor to work their farms before and after the Civil War. It is beyond the scope of this document to review all of the Griffith Montgomery County landholdings. By 1824, however, Lyde Griffith had accumulated sufficient capital to acquire nearly 1,200 acres which he named “Griffith’sburg” (Griffithsburg).[8]

Chrome Mining

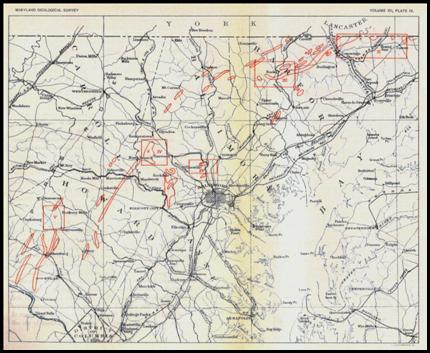

Lyde Griffith’s 1,196-acre farm was located in the Upper Patuxent River drainage and was dissected by several unnamed tributaries. The geology of this area includes serpentine rock formations rich with chrome ore. According to Maryland Geological Survey maps, the serpentine formations near Etchison run from southwest to northeast.[9] Chrome is a mineral that in the nineteenth century was used in the manufacture of steel, the leather industry, and as a pigment. The American chrome industry was founded in the first quarter of the nineteenth century by Baltimore entrepreneur Isaac Tyson Jr. Tyson’s career and contributions to American and Maryland economic history are discussed at length in articles on the chrome industry and in several biographies.[10]

Lyde Griffith appears to have realized by the mid 1830s that his lands held merchantable quantities of chrome. In October 1837 Griffith executed a contract with Washington Waters allowing Waters to remove chrome from the property. According to the contract, Waters, for $50, bought the right to “search for, dig, and remove, as he may think proper, chrome ore or mineral from the lot of ground marked out for him.” Waters also obtained, “the use of the house, except the cellar, in said lot, so long as he may wish it, for the use of the hands he may employ in digging for chrome.”[11]

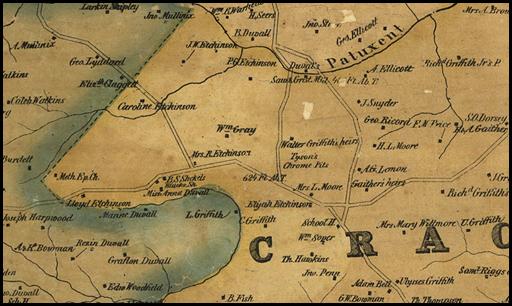

Less than a year into the contract with Waters Griffith apparently began negotiating with Tyson to mine chrome from the farm. These negotiations spurred a breach of contract suit involving Waters and Lyde Griffith’s heirs. Waters was awarded $2,056.25 in damages and Griffith’s heirs appealed the judgment to the Maryland Court of Appeals. The portion of Griffith’s property mined by Waters was a tract formerly owned by Benjamin King and bought by Griffith in 1824.[12] This appears to be the farm that came to be held by Columbus Griffith and which is now south of Damascus Road.[13] Records consulted to date do not indicate if there were chrome pits active within the 89 acres now comprising the Col. Lyde Griffith Farm. The 1865 Martenet and Bond Montgomery County map show “Tyson’s Chrome Pits” in the vicinity of the Col. Lyde Griffith Farm.[14]

The Etchison chrome mines were the only ones active in Montgomery County.[15] The earliest known description of the place where chrome was removed starting in c. 1837 is in a Johns Hopkins University publication from 1889. “On the land of Columbus Griffith, a mile west of Etchison P.O., and a little east of Great Seneca Creek, is a considerable deposit of chromite … This was formerly worked for chrome ore,” reported A.C. Gill. Gill also described “old dump –heaps which surround the pits.”[16]

In 1926 geologist Earl Shannon wrote in the Journal of the Mineralogical Society of America:

An old chromite mine near Etchison in Maryland has been mentioned by Gill as a locality for chrome tourmaline and fuchsite and the present writer has recently described a green margarite from this region. The mine now consists of a shallow depression surrounded by dumps, somewhat overgrown with briars. The only rock exposed in place is a mass of rusty talc in the pit. Beneath this talc outcrop is an old tunnel which still shows a narrow opening but, since no light was available, this was not explored.[17]

Two years after Shannon’s article was published, Joseph Singewald wrote on the Chrome Industry in Maryland in a report published by the Maryland Geological Survey and he described the “Etchison Mine”:

On the farm of Columbus Griffith three-quarters of a mile west of Etchison, chrome ores were mined off and on several times prior to the Civil War and hauled to Woodbine for shipment. There appears to have been three openings. The largest and only accessible one shows no evidence of chrome ore. It consists of a pit 30 feet in diameter and 15 feet deep from which a gallery runs with a steep down grade for 50 feet N. 20° W. and then turns N. 70° E. for 30 feet. The country rock is a soft talcost schist with the direction of N. 70° W. 30° N. A second opening 80 feet distant in the direction N. 35° E., and a third 50 feet N. 75° E. of the second are now completely filled up but small dumps about them contain serpentine in which there are metallic particles but no pieces of massive chromite could be found. The indications are that not much ore was produced here. [Endnote did not copy: Singewald, “The Chrome Industry in Maryland,” 191.]

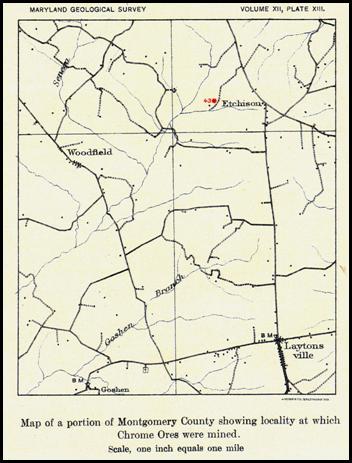

Maryland Chrome Mines. Map published by the Maryland Geological Survey in 1928. The 1928 color plate appears to have been derived from maps created as early as 1919 and published in articles on Maryland's chrome industry.

Singewald’s article also contained a map precisely locating the Etchison mine :

The documents available suggest that the chrome extraction occurred on portions of the former Lyde Griffith property outside of the boundaries of the farmstead now known as the Col. Lyde Griffith Farm. Aerial photographs and United States Geological Survey topographic maps, along with the 1865 Martenet and Bond map, suggest that the wooded portions now within the Col. Lyde Griffith Farm could have been exploited for chrome. These areas require an archaeological evaluation to determine if chrome was extracted in this portion of the former 1,196-acre Griffith property.

Griffith Family Cemetery

Although there appears to be no evidence of the Griffith family cemetery visible, the graves may still be intact and their location delineated using non-destructive archaeological methods (e.g., ground penetrating radar, surface survey, etc.).

Griffith Family Cemetery. Photos included in 1973 MIHP form on file with the Maryland Historical Trust

Other Archaeological Components

Historical photographs and earlier MIHP forms show a large Pennsylvania German bank barn at the farm. Demolished after the farm was first surveyed by M-NCPPC, the barn and its associated yard area may contain significant archaeological data that could amplify and expand the surviving historical record. Furthermore, in addition to the surviving I-house, other domestic buildings may have been located within the current property’s boundaries. These buildings may have been occupied by Griffith family members or by agricultural and industrial (mine) workers. Privies and other outbuildings, if preserved archaeologically, also could contribute to a more complete understanding of Lyde Griffith and his heirs through the architecture they preferred and the objects made and bought, used, and discarded at the farm through time.

Bank barn, privy, and other buildings and structures photographed by M-NCPPC historian Mike Dwyer in 1973.

NOTES

[1] Clare Lise Kelly and Rachel Kennedy, Etchison, Maryland Inventory of Historic Properties Form, November 2009.

[2] Clare Lise Kelly and Lorin Farris, Col Lyde Griffith Farm (M-15/73), Maryland Inventory of Historic Properties Form, December 2009.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Henry H Glassie, Pattern in the Material Folk Culture of the Eastern United States (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1969); Henry H Glassie, Vernacular Architecture (Philadelphia: Material Culture, 2000); Henry H Glassie, Folk Housing in Middle Virginia: A Structural Analysis of Historic Artifacts, 1st ed. (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1975).

[5] Sandra Youla and Clare Lise Kelly, Staff Report. Staff Draft Amemdment to the Master Plan for Historic Preservation: Upper Patuxent Area Resources, January 13, 2010, 3-4.

[6] Joshua Dorsey Warfield, The Founders of Anne Arundel and Howard Counties, Maryland; a Genealogical and Biographical Review from Wills, Deeds, and Church Records (Baltimore: Regional Pub. Co, 1967); Emily Griffith Roberts, Ancestral Study of Four Families: Roberts, Griffith, Cartwright [and] Simpson (Terrell? Tex., 1939); Maxwell Jay Dorsey, The Dorsey Family: Descendants of Edward Darcy-Dorsey of Virginia and Maryland for Five Generations, and Allied Families ([Urbana, Ill.?: M.J. Dorsey, 1947).

[7] “He was called ‘Colonel Griffith’ too. We haven’t been able to determine why. Perhaps it was a term of respect for this gentleman but we don’t know exactly why,” Clare Lise Kelly, Worksession to consider the Staff Draft Amendment to the Master Plan for Historic Preservation: Upper Patuxent Area Resources (Silver Spring, Md, 2010). The MIHP form completed by staff states, “Perhaps he served in the War of 1812,”Kelly and Farris, Col Lyde Griffith Farm (M-15/73). William M. Marine, The British invasion of Maryland, 1812-1815 (Hatboro, Pennsylvania: Tradition Press, 1965), 305; General Society of the War of 1812, Register of the General Society of the War of 1812 (Washington, 1972), 308.

[8] Staff wrote that Griffith patented the tracts in 1826.Kelly and Farris, Col Lyde Griffith Farm (M-15/73). Although the land patent was filed in 1826, earlier survey documents show that Griffith began laying out his Griffithsburg tracts in late 1824.

[9] Joseph T. Singewald, “The Chrome Industry in Maryland,” Maryland Geological Survey Reports 12 (1928): 158-191.

[10] Collamer M. Abbott, “Isaac Tyson, Jr.: Pioneer Industrialist,” The Business History Review 42, no. 1 (Spring 1968): 67-83; William Glenn, “Biographical Notice of James Wood Tyson,” Transactions of the American Institute of Mining Engineers 31 (1902): 118-121; Johns Hopkins University, Maryland, Its Resources, Industries and Institutions (Baltimore: The Sun Job Printing Office, 1893); William Glenn, “Chrome in the Southern Appalachian Region,” Transactions of the American Institute of Mining Engineers 25 (1896): 481-499; Joseph T. Singewald, “Maryland Sand Chrome Ore,” Economic Geology 14, no. 3 (May) (1919): 189-197; Singewald, “The Chrome Industry in Maryland”; United States National Museum, Report upon the condition and progress of the U.S. National Museum during the year ending June 30 … (G.P.O., 1901), 249; “Maryland’s Geologic Features: Soldiers Delight Serpentine Barrens, Baltimore County,” http://www.mgs.md.gov/esic/features/soldiers.html.

[11] Washington Waters vs. Lyde Griffith, Executor of Lyde Griffith, deceased, 2 Maryland Reports 326 (1852).

[12] Montgomery County Land Records. Liber X, folio 497, Benjamin King to Lyde Griffith.

[13] In 1879 Lyde Griffith (descendant) had Griffithsburg resurveyed and the King tracts are clearly shown in the southern portion of the original Griffithsburg survey.“Resurvey on Part of Griffithsburg,” May 8, 1879, Maryland State Archives.

[14] Simon J. Martenet, “Martenet and Bond’s Map of Montgomery County, Maryland” (Baltimore: Simon J. Martenet, 1865).

[15] Additional research in Isaac Tyson’s business papers held at the Maryland Historical Society may change this assertion. According to a contract Tyson executed in 1836, he secured the rights to prospect for and remove chrome from lands owned by a Mary Costigan. Montgomery County Land Records Liber BS 7, folio 522.

[16] A.C. Gill, “Notes on Some Minerals from the Chrome Pits of Montgomery County, Maryland,” Johns Hopkins University Circulars, September 1879, 100.

[17] Earl V. Shannon, “Mineralogy of the Chrome Ore from Etchison, Montgomery Co., MD.,” The American Mineralogist 11, no. 1 (1926): 16.