Last night the Montgomery County Historic Preservation Commission concluded its latest work session on the Upper Patuxent Master Plan Amendment for Historic Preservation designations begun near the end of my term as HPC chairman. Now that the HPC has reviewed and voted on all of the properties contained in the proposed amendment, the next step in the process is evaluation by the Montgomery County Planning Board. [Correction: This refers to the draft amendment prepared in December 2009. There will be one additional meeting to evaluate properties culled from the previously proposed Etchison and Clagettsville HDs.]

From the first time I received the amendment documents last December I was troubled by the quality of the research done by Historic Preservation staff in making the recommendations for designation to the Master Plan for Historic Preservation or in recommending removal from the Locational Atlas and from future consideration for designation. Some of the properties, like the two proposed historic districts — Etchison and Clagettsville — appeared to lack cohesion and contained an unsettling number of noncontributing properties, i.e., properties constructed after the proposed districts’ period of significance or properties that lacked integrity and/or historical associations. The proposed Clagettsville Historic District, for example, had more than 30% (12) of its 37 properties identified as “non-contributing.” HP staff failed to disclose prior to the completion of January 2010 staff report that the Clagettsville Historic District had been reviewed by the Maryland Historical Trust. The 1991 Determination of Eligibility report, based on documentation prepared by then-M-NCPPC historian Mike Dwyer, noted “The crossroads community of Claggettsville has undergone numerous alterations and has many intrusions. It no longer conveys the sense of a 19th and early 20th century village and lacks sufficient cohesiveness to be considered a district.”[1] The HPC voted February 24, 2010, to not recommend designation of the Clagettsville Historic District.

The December 2009 Maryland Inventory of Historic Properties form HP staff completed for the proposed Etchison district included language suggesting that the proposed historic districts many postwar ranch houses were significant elements because they had achieved an exceptional level of significance:

The period of significance for the district is from 1876‐1965. The residences built at the end of this range, even though not yet attaining 50 years of age, qualify under Criterion Consideration G for exceptional significance, representing continuity of tradition in this kinship community.[2]

Leaving aside the issue that Montgomery County does not designate properties based on the National Register of Historic Places Criteria for Listing (and the supplementary Criteria Exceptions), there was no evidence presented to support that the postwar ranch homes rose to the level of meeting any of the designation Criteria listed in Chapter 24A of the Montgomery County Code and the HPC at its February 24, 2010, meeting declined to recommend designation of the full district as proposed by staff.

The Master Plan amendment’s individual resources also had substantial problems. The documentation prepared for the Parr’s Spring property marking the point where Montgomery, Frederick, Carroll, and Howard counties meet failed to adequately inform the HPC whether the original early federal period boundary marker remained in place beneath the spring’s waters. The paucity of defensible documentation prompted one new HPC member to remark that it appeared that staff was asking the HPC to designate a Master Plan property based on “folklore.”

The Master Plan amendment was prepared by multiple staff members, some of whom are no longer working for Montgomery County. The documents themselves were inconsistent and did not contain sufficient information for the HPC, not to mention the Planning Board or County Council, to make defensible decisions about whether properties met the Criteria for Designation in Chapter 24A. For example, several properties lacked contemporary photographs and staff relied on low-resolution aerial photos, scanned 1970s inventory forms, and digitally zoomed photos taken from public rights of way to provide the HPC with information on the architecture (construction detail, materials, integrity) of farmhouses and other buildings. The HP staff’s explanation was that they did not have access to the properties. Okay then, what was staff asking the HPC to use as evidence for recommending designation or removal from the Locational Atlas?

At last night’s final work session the HPC considered seven properties. Among the properties the HPC evaluated was the Col. Lyde Griffith Farm, an early nineteenth century property covering approximately 88 acres. Staff was unable to provide the HPC with contemporary photos of the property, which includes what appears to be an early nineteenth century I-house, a 1930s-era gambrel-roof dairy barn complex, and other agricultural and domestic outbuildings. Historical documents and oral histories add to the inventory within the farmstead: a nineteenth century family cemetery, the ruins of a Pennsylvania German bank barn, and antebellum chrome mines.

The HPC repeatedly asked staff for details of the farmstead’s architecture, i.e., specific dates for buildings, their integrity, and the location of potentially significant archaeological resources related to the mixed agricultural-domestic-industrial use at the property between the 1820s and the Civil War. Staff was unable to answer the questions to the HPC’s satisfaction and the HPC voted unanimously to remove the property from further consideration as a Master Plan property.

Troubling as the two proposed historic district designations were because of the potential to place undue regulatory burdens on property owners, the HPC’s decision to not recommend designation of the Col. Lyde Griffith Farm was perhaps the most troubling outcome from the Upper Patuxent proceedings. Based on the wealth of information available to HP staff — i.e., they had collected primary historical documents and cited them in their reports but failed to read or understand them — this property clearly met all of the associational Criteria for Designation, e.g., it has character, interest or value as part of the development, heritage or cultural characteristics of the county, state or nation (for nineteenth century farmsteads, role in chrome extraction industry); it Is identified with a person or a group of persons who influenced society; and, it exemplifies the cultural economic, social, political or historic heritage of the county and its communities.[3]

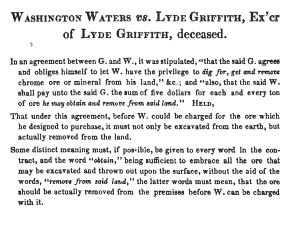

The American chrome industry was born in Baltimore in the early nineteenth century. A family of metals entrepreneurs, the Tysons, founded processing and extraction sites throughout Southeastern Pennsylvania and northern Maryland. They leased chrome pits and mines on farms like Griffith’s throughout the region. We know that Griffith had been leasing his farmstead to chrome extractors since at least 1837 when he executed a contract with Washington Waters to mine and remove the chrome from Griffith’s farm. Shortly after executing that contract Griffith began negotiating with the Tysons for them to lease the property for chrome extraction. Waters sued Griffith for breach of contract and the case was litigated, appealed, and reported in 1852.[4] The appeals court case included explicit descriptions of the Griffith property and the rights afforded to lessees to use the farmhouse and other buildings for housing workers, etc.:

The American chrome industry was born in Baltimore in the early nineteenth century. A family of metals entrepreneurs, the Tysons, founded processing and extraction sites throughout Southeastern Pennsylvania and northern Maryland. They leased chrome pits and mines on farms like Griffith’s throughout the region. We know that Griffith had been leasing his farmstead to chrome extractors since at least 1837 when he executed a contract with Washington Waters to mine and remove the chrome from Griffith’s farm. Shortly after executing that contract Griffith began negotiating with the Tysons for them to lease the property for chrome extraction. Waters sued Griffith for breach of contract and the case was litigated, appealed, and reported in 1852.[4] The appeals court case included explicit descriptions of the Griffith property and the rights afforded to lessees to use the farmhouse and other buildings for housing workers, etc.:

The defendant then offered in evidence the following receipt: 1838, January 30th, Received of Washington Waters, $50 in full, for the entire right to search for, dig, and remove, as he may think proper, chrome ore or mineral from the lot of ground marked out for him, upon the terms specified in a contract between him and myself, dated, October 18th 1837. Also for the use of the house, except the cellar, in said lot, so long as he may wish it, for the use of the hands he may employ in digging for chrome upon said lot.[5]

We know that the Tysons did in fact secure the lease to remove chrome from the Griffith property because the 1865 Martenet and Bond Map of Montgomery County shows the “Tyson Chrome Pits” at the location now known as the Col. Lyde Griffith Farm.[6] What remains unclear and which should have been explored by staff is how the antebellum chrome extraction site identified in Waters v. Griffith relates to what appears to be a second Griffith chrome extraction site, also mined by lease, located southwest of the Col. Lyde Griffith Farm and documented between the 1890s and 1929 by the Maryland Geological Survey.

According to one writer, in 1928 the “Etchison Chrome Mine” was:

On the farm of Columbus Griffith three-quarters of a mile west of Etchison, chrome ores were mined off and on several times prior to the Civil War and hauled to Woodbine for shipment. There appears to have been three openings ….[7]

Another writer, in 1926, observed, “The mine now consists of a shallow depression surrounded by dumps, somewhat overgrown with briars.”[8]

Maps published in various Maryland Geological Survey reports place the mine described on property southwest of Damascus Road yet the historical record reviewed thus far does not identify two distinct mining operations active on the Griffith properties. HP staff should have ensured that the HPC had sufficient information to know which chrome extraction operation was active at what is now known as the Col. Lyde Griffith Farm and HP staff should have been better prepared to address the HPC’s questions about the individual elements within the Col. Lyde Griffith Farm.

As it stands now, the Planning Board will receive a Master Plan amendment fraught with errors with long-term implications for Montgomery County’s history and its property owners. I will update this blog post with more details from last night’s hearing and a future post will cover the significance of Montgomery County’s only chrome extraction site.

NOTES

[1] Elizabeth Harrold, Claggettsville Historic District (M-15-8), Individual Property/District Maryland Historical Trust Internal NR-Eligibility Review Form (Crownsville, MD: Maryland Historical Trust, September 20, 1991).

[2] Clare Lise Kelly and Rachel Kennedy, Etchison, Maryland Inventory of Historic Properties Form, November 2009.

[3] Chapter 24A §3(b)(1).

[4] Washington Waters vs. Lyde Griffith, Executor of Lyde Griffith, deceased, 2 Maryland Reports 326 (1852).

[5] Ibid.

[6] Simon J Martenet, Martenet & Bond, and Schmidt & Trowe, “Martenet and Bond’s Map of Montgomery County, Maryland” (Baltimore: Simon J. Martenet, 1865).

[7] Joseph T. Singewald, “The Chrome Industry in Maryland,” Maryland Geological Survey Reports 12 (1928): 191.

[8] Earl V. Shannon, “Mineralogy of the Chrome Ore from Etchison, Montgomery Co., MD.,” The American Mineralogist 11, no. 1 (1926): 16.