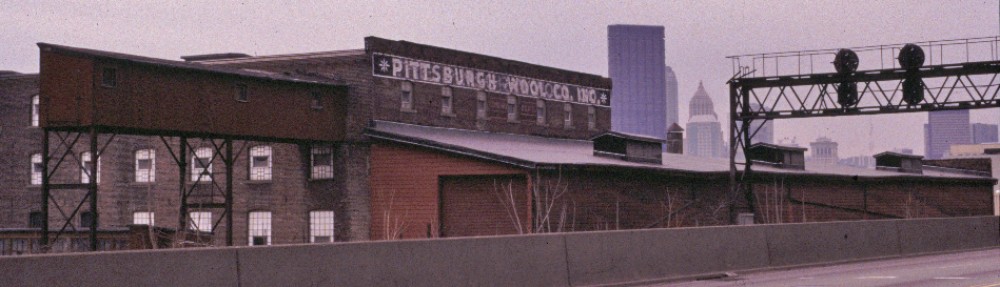

Canal boat mural by Laurie Lundquist, Pennsylvania Route 28 retaining wall, Pittsburgh. Photo by David Rotenstein.

I recently met a man who looked at a hillside in a highway corridor and he saw canal boats instead of concrete retaining walls. The man is Jack Schmitt and we met during a walking tour in the Pennsylvania Route 28 highway corridor along the Allegheny River in Pittsburgh. Schmitt is a historic preservation activist who was a catalyst the Pennsylvania Department of Transportation (PennDOT) decision to explore alternative approaches to mitigating the impacts of destroying an entire neighborhood along Route 28.

My article on Schmitt and how his work fits into emerging national trends in historic preservation has just been published in the National Council on Public History’s History@Work site. This post digs a little deeper into Schmitt’s advocacy with PennDOT.

My first conversation with Schmitt took place during an Allegheny City Society walking tour in May 2019. We met again in June at a Pittsburgh sandwich shop and I ran an audio recorder during our 90-minute chat. I also had a long history with Route 28 and the historic resources there. The former tannery buildings and the derelict industrial landscape comprised the core of the 1997 Pittsburgh History cover article that I wrote about Pittsburgh’s leather industry. The walking tour, my recent move back to Pittsburgh, and the conversation with Schmitt brought me back to a consequential episode in my professional history.

I wanted to revisit some of my understandings about the Route 28 project with the benefit of the subsequent 20 years of complicated regulatory compliance consulting and my research into how history and historic preservation are produced. This blog post and my History@Work essay are my first steps in this process.

Towards Better Mitigation

Jack Schmitt didn’t think much of PennDOT’s approach to mitigating the Route 28 impacts to historic properties. In fact, he questioned if the agency even had a mitigation plan. And what is mitigation? Mitigation represents the steps a government agency must take to compensate a community for destroying or polluting its natural or cultural resources. Most often mitigation comes in the form of reports and photographs that no one will ever read or see and archaeological excavations. Other times, it’s a flat-out bribe: An agency throws some money for historical research or a museum exhibit and calls it square.

The archaeologist and prolific regulatory compliance critic Tom King knows mitigation and how it is misunderstood and abused. In one of our many exchanges on the subject, King wrote to me in 2018, “Mitigation is widely and incorrectly understood to mean shitty compensation.” Yet, that’s frequently what results from poorly executed historic preservation research work done in coordination with a project that will destroy someplace or something people in some community value.

As a resident of one such community, Schmitt wanted better from PennDOT. Schmitt saw the steep hillside in the corridor as an opportunity. “There was going to be walls on the north side of the road and we tried to get them looking better,” he told me. “They were just going to be poured concrete walls like all the other bypasses.”

Pennsylvania Route 28 retaining wall in Etna, north of Pittsburgh.

Schmitt’s solution was to reach out to the American Canal Society to get the rights to use an image of a canal boat. Schmitt envisioned creating a visual history lesson using the new retaining walls. “As you drove along the highway, you would be passing canal boats with mules and you would get the feeling of what was happening there at one time in history,” he explained.

Canal boat image Schmitt proposed using in Pennsylvania Route 28 retaining walls.

PennDOT balked. What ended up being built were retaining walls using concrete shaped and treated to appear like stones used in Pennsylvania Canal locks. And, one of the five murals depicting images drawn from the corridor’s history did include a canal boat being drawn by mules — it is twice the size of the other murals (see the first photo in this post). Read the History@Work post to learn more about the murals and the artist who designed and executed them.

In the remainder of this post, I’d like to spend a little more time on the concept of mitigation and how folks in the real world (i.e., those who don’t work for state and federal agencies or people who aren’t cultural resource management consultants) see mitigation.

I asked Schmitt if he thought that PennDOT had fulfilled its obligations to comply with Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act. “I think they tried very hard and they did a lot. I have to give them credit for that,” said. Schmitt concedes that his opinion might be more positive if the historic St. Nicholas Croatian Catholic Church had not been demolished. The reasons why the church, which was located in the corridor, was demolished are complicated and not fully tied to the road project.

St. Nicholas church demolition, 2013. Pittsburgh Tribune-Review photo.

With the church gone and all of the homes, businesses, and industrial sites along with it, I asked Schmitt how people will learn about the community’s history. Schmitt replied, “The people learn about the community through their living memory and their oral traditions. They’re talking about that even now.” The murals, historical markers, and commemorative features at the demolished church site will help.

Former St. Nicholas church site with reproduced grotto, bronze tower base outline, and historical markers, June 2019.

Towards the end of our conversation in the restaurant, Schmitt recounted something he told an individual whose first involvement with the Route 28 project was as a volunteer in the effort to save St. Nicholas. That individual later went to work for an engineering company that does Section 106 work. Schmitt said,

I used to kid him. I said, “You were in historic preservation and now you’re in historic destruction cover-up.” I said, “You make the case for these historic things and then you mitigate them by saying we said this.” I said, “You can’t just say this, put it in a book in the library on the shelf and it doesn’t help the neighborhood to mitigate that terrible loss.”

I think that the murals and other treatments in the Route 28 corridor make great strides towards mitigating the loss of the buildings and the community. Like Schmitt, I have issues with the final results. There’s a lot missing and much of the historical knowledge that informed PennDOT’s decision-making was flawed. I only wonder what might have happened in the corridor had the agency understood what made the place special to the people who valued it. If the agency had understood and fulfilled its obligations under the National Historic Preservation Act, completing the project might have been a whole lot smoother, less expensive, and the mitigation might have been more collaborative, memorable, and meaningful.

Read the complete History@Work post on the murals and creative mitigation: https://ncph.org/history-at-work/community-driven-mitigation/.

© 2019 D.S. Rotenstein

Like this:

Like Loading...

The editor of a monthly Pittsburgh neighborhood newspaper recently asked me to cover a

The editor of a monthly Pittsburgh neighborhood newspaper recently asked me to cover a

In 1968, Congress held hearings on the violence that erupted after Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s April assassination. Testimony by Rufus “Catfish” Mayfield exposed how fraught the U.S. Census is with regard to communities of color. Mayfield’s candid testimony about how some of Washington’s African American residents responded when the census taker knocked on the door is worth considering as the current U.S. President plays political games with the 2020 Census.

In 1968, Congress held hearings on the violence that erupted after Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s April assassination. Testimony by Rufus “Catfish” Mayfield exposed how fraught the U.S. Census is with regard to communities of color. Mayfield’s candid testimony about how some of Washington’s African American residents responded when the census taker knocked on the door is worth considering as the current U.S. President plays political games with the 2020 Census.