I have been interested in concealed telecommunications sites since I first began working on regulatory compliance for Federal Communications Commission (FCC) licensees struggling to understand the complexities of Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act. This is the first of a series of posts on concealed telecommunications infrastructure and the American landscape.

Monthly Archives: July 2010

Creating Community

Last night my BlackBerry and I stumbled through near-100-degree heat into the second weekly drum circle convened in the new Veteran’s Plaza by Impact Silver Spring.

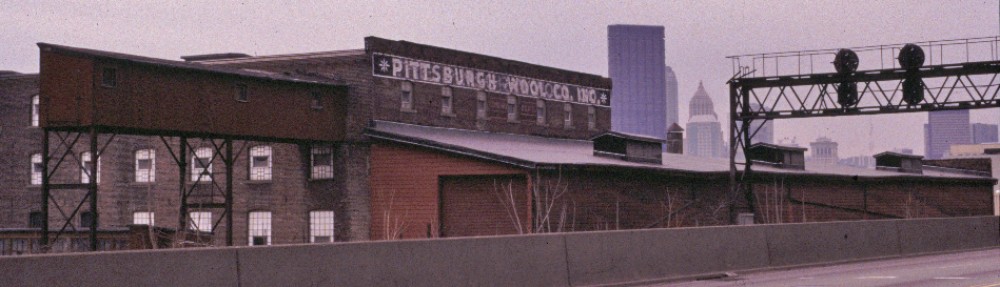

Silver Spring is an interesting place. I’ve lived here for nearly 10 years and I still feel like a newcomer. It is an unincorporated place in southern Montgomery County (Maryland) that hugs Washington’s angular northern boundary line. Unlike other places I have lived (e.g., Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, Atlanta), there is no cohesive Silver Spring identity for the community as a whole or its various neighborhoods. It’s a place in search of a culture, it seems.

Two years ago the space where the new Veterans Plaza and Civic Building now sit was a patch of artificial turf that became a community gathering place. One year ago the spot was a construction site. County planners envisioned the new space as a performance space and a formal and informal gathering place. I wonder how this is going to develop and if Silver Spring will get the culture planners hoped for in building the new space. Okay, they’ve built it and people are coming: skateboarders, loafers, nappers, and voyeurs. And the drummers. Are the drum circles a transitional phase helping (through music therapy?) to move Silver Spring into a new direction? Or are they something else? I look forward to watching how things turn out.

I spent about 45 minutes at last night’s drum circle (it was more of a rectangle with an amorphous fringe) and I wish I could have stayed longer. I enjoyed the improvisation and watching the diverse crowd. I wonder how things turned out with the Krishnas who set up an informational table a few dozen yards away, complete with their own drum.

Philly Folk Festival Season

Each summer Google directs dozens of visitors looking for information on the history of the annual Philadelphia Folk Festival. This year’s festival runs from August 20 through the 21st and the hits to my site are already picking up. Why is Google sending folks to my Web site? Because in the 1990s I covered folk music for the Philadelphia Inquirer and in advance of the 1992 festival I wrote a Sunday feature on the festival’s history and the folks behind it: The Philadelphia Folksong Society. I was finishing up my coursework at Penn at the time and I just happened to be enrolled in the now-defunct doctoral program in Folklore and Folklife. I also happened to be gearing up for the required FOLK 606: History of Folklore Studies class taught by the inimitable Dan Ben-Amos and I decided to use some of the reporting I did for the Inquirer article for one of my class papers. Since my time at Penn coincided with my early years writing about music I got to use interviews with folks like BB King and others as source material for term papers. Now that was cool.

For the Folk Festival story (and subsequent paper) I interviewed legendary Philly radio personality Gene Shay and many of the festival’s founders. I also interviewed Irish musician (and fellow Penn folklorist) Mick Moloney as well as George Britton (who died recently). Britton was a fun interview. Near the end of our interview he sang the chorus of a tune he wrote about the festival. He called the song, “Barefoot, Bearded and Bedraggled”:

I’m barefoot, bearded and bedraggled

Stoned and drunk as I can be

I’m the counterculture and I’m all folked up

This here’s my cry of liberty. Continue reading

On the Map!

Civil Defense

What would you do if you were sitting at the dinner table and a loud buzzer went off to inform you that the federal government had detected inbound nuclear missiles? Back in the late 1950s and early 1960s the government market-tested and field tested the National Emergency Alarm Repeater device to provide just such a warning.

The Undisclosed Location Disclosed: Continuity of Government Sites as Recent Past Resources

By David S. Rotenstein

[08/22/2011: Update: Read the follow-up post on newly identified photos showing the construction of the Fort Reno “Cartwheel” facility in Washington, DC]

In 2004 the State of Maryland was both project proponent and regulatory reviewer in the Section 106 consultations tied to the construction of a proposed telecommunications tower at Lamb’s Knoll, a mountaintop ridge that straddles Washington and Frederick counties west of Frederick. A Federal Communications Commission licensee, the State was required to identify historic properties, evaluate their significance under the National Register Criteria for Evaluation, and determine whether the proposed project would adversely affect properties listed in or eligible for listing in the National Register of Historic Places. Properties likely affected at Lamb’s Knoll included the Appalachian Trail, a 1920s fire observation tower turned telecommunications tower, and a Cold War-era army facility.

Maryland’s agency for emergency telecommunications infrastructure retained a cultural resource management firm to conduct the Section 106 compliance studies. The firm’s initial 2003 report noted the presence of nearby nineteenth century farmsteads and surrounding Civil War battle sites, but there was no mention of the twentieth century resources.[1] The Maryland Historical Trust (the state historic preservation office) reviewed the 2003 report and concurred with its authors that no historic properties would be affected by construction of the proposed tower. Located less than 500 feet from the proposed tower site and rising approximately 100 feet above the mountaintop, the former Cold War facility was notably absent from all discussions turning on historic preservation and the proposed tower. Hidden in plain sight and visible from miles around, the Lamb’s Knoll facility is one of a handful of continuity of government sites built in Maryland, Pennsylvania, Virginia, West Virginia, and Washington, D.C., that were designed to house large numbers of federal officials in underground bunkers while the exposed concrete towers that housed sophisticated radio equipment kept communications open among the survivors, the military, and civilian populations.

This article stems from my involvement in that 2004 project. I was retained by a coalition of environmental groups including the Harpers Ferry Conservancy and the National Trust for Historic Preservation to evaluate the historic properties the groups believed that the State’s consultant failed to identify in the initial round of Section 106 consultation. Between 2001 and 2008 I did many Section 106 projects for FCC licensees and I had been working on histories of postwar telecommunications networks.[2] By the time I had been brought into the Lamb’s Knoll project I was sensitive to the historical significance embodied in telecommunications facilities like the repurposed fire lookout tower and the Cold War facility.

The H4H YouTube Channel is now live

Unbuilding Trades

A Levitt Encounter

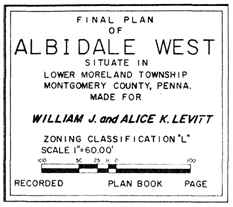

Architectural and cultural historians for decades have been tuned into the significance of the sprawling Postwar suburbs built by Levitt & Sons bearing the family firm’s name. Recent research into other Levitt developments like Belair in Bowie in the Washington, D.C., suburbs has expanded our understanding of the Levitts’ impact on modern cultural landscapes and in shaping American homeownership. Last week while doing some fieldwork in the Philadelphia suburbs I encountered a 1960s subdivision planned by firm president William J. Levitt (1907-1994).

Architectural and cultural historians for decades have been tuned into the significance of the sprawling Postwar suburbs built by Levitt & Sons bearing the family firm’s name. Recent research into other Levitt developments like Belair in Bowie in the Washington, D.C., suburbs has expanded our understanding of the Levitts’ impact on modern cultural landscapes and in shaping American homeownership. Last week while doing some fieldwork in the Philadelphia suburbs I encountered a 1960s subdivision planned by firm president William J. Levitt (1907-1994).

Named Albidale — Al (for Alice K. Levitt) and bi (for Bill Levitt) plus the rustic-sounding dale — the development included two tracts culled from a large 600-acre horse farm and steeplechase track assembled by Philadelphia philanthropist George W. Elkins (1886-1954) begun in the 1920s. Albidale’s core, dubbed Albidale West by Levitt, includes a cluster of stone homes Elkins built in 1936 for his employees and a pair of eighteenth century stone houses that once were part of farms Elkins bought in the 1920s and 1930s for his expansive Justa Farm complex.

Albidale West Plat. Montgomery County Land Records.

Earlier this year a new book on Pennsylvania’s Levittown, Second Suburb, was published and I have now moved my copy to the top of my reading list. The Levitts were fresh in my mind before I did last week’s fieldwork because I had just read Jamie Jacobs’ chapter on Belair in Richard Longstreth’s new book, Housing Washington. Jacobs’ 2005 dissertation has a valuable discussion of suburban real estate marketing techniques that I am using in my work on Silver Spring’s 1939 World’s Fair Home. Two things intrigue me about Levitt and they are beyond the scope of my current research project: 1) Levitt did not scrape away all evidence of the 18th, 19th, and early 20th centuries to make way for his development; and, 2) Levitt and his wife briefly lived in one of the Elkins houses. Continue reading