In 2007 and 2008, I did more than 60 oral history interviews and documentary research for Washington’s Local Initiatives Support Corporation (LISC) office. This week, LISC celebrated its 30th anniversary in Washington and it released a book derived from the interviews, written by community development expert Tony Proscio. Continue reading

Tag Archives: History

Historic Parkwood: An Early DeKalb County Ranch House

Parkwood was one of the last subdivisions developed in Historic Druid Hills. The first post in this series explored how Parkwood’s landscape developed between c. 1920 and 1960. The research presented in that introduction shows that there were three periods of historic development inside Parkwood: 1927-1939; 1940-1947; and 1948-1952.

Houses built in the earliest phase were executed in the period revival and bungalow styles popular at the time; homes built in the middle phase bridged the revival styles and included early ranch houses; and, the homes built in 1948 and afterwards were almost exclusively ranch houses. This post explores the history of one of the earliest ranch houses constructed in Parkwood during the middle phase, in 1946. Continue reading

The R.M.S. Carmania: 1905 Maiden Voyage

I grew up in Daytona Beach, Florida. One of the childhood pastimes that I developed — and which led to a career in history and archaeology — was exploring abandoned buildings. Whether you call it “urban exploration” or “creeping” today, back in the 1970s I called it fun. My favorite spots were old houses awaiting teardown (in Daytona that meant 1930s vintage) and an old Atlantic Bank building. The bank building was the most fun: entry was gained through a broken drive-through window and from there you get to all of the other drive-through windows and the main bank building. Lying around were blank bank documents, some business records, and lots of trash left by vagrants and fellow trespassers who took up residence in this building located just three blocks from the beach. Continue reading

Unmaking Uncle Tom’s Cabin (Updated)

In 2006 Montgomery County, Maryland, received international attention for purchasing a 19th century farmhouse that oral tradition suggested was the original “Uncle Tom’s Cabin.” The county paid $1 million for a little over an acre in suburban North Bethesda. Now, four years later the county is holding community stakeholder meetings to map out the future of what officials are now calling The Josiah Henson Site. I recall the excitement surrounding the announcement that the legendary material link to American literary and social history would be “saved” from land hungry developers gobbling up Montgomery County real estate. Continue reading

The Undisclosed Location Disclosed: Continuity of Government Sites as Recent Past Resources

By David S. Rotenstein

[08/22/2011: Update: Read the follow-up post on newly identified photos showing the construction of the Fort Reno “Cartwheel” facility in Washington, DC]

In 2004 the State of Maryland was both project proponent and regulatory reviewer in the Section 106 consultations tied to the construction of a proposed telecommunications tower at Lamb’s Knoll, a mountaintop ridge that straddles Washington and Frederick counties west of Frederick. A Federal Communications Commission licensee, the State was required to identify historic properties, evaluate their significance under the National Register Criteria for Evaluation, and determine whether the proposed project would adversely affect properties listed in or eligible for listing in the National Register of Historic Places. Properties likely affected at Lamb’s Knoll included the Appalachian Trail, a 1920s fire observation tower turned telecommunications tower, and a Cold War-era army facility.

Maryland’s agency for emergency telecommunications infrastructure retained a cultural resource management firm to conduct the Section 106 compliance studies. The firm’s initial 2003 report noted the presence of nearby nineteenth century farmsteads and surrounding Civil War battle sites, but there was no mention of the twentieth century resources.[1] The Maryland Historical Trust (the state historic preservation office) reviewed the 2003 report and concurred with its authors that no historic properties would be affected by construction of the proposed tower. Located less than 500 feet from the proposed tower site and rising approximately 100 feet above the mountaintop, the former Cold War facility was notably absent from all discussions turning on historic preservation and the proposed tower. Hidden in plain sight and visible from miles around, the Lamb’s Knoll facility is one of a handful of continuity of government sites built in Maryland, Pennsylvania, Virginia, West Virginia, and Washington, D.C., that were designed to house large numbers of federal officials in underground bunkers while the exposed concrete towers that housed sophisticated radio equipment kept communications open among the survivors, the military, and civilian populations.

This article stems from my involvement in that 2004 project. I was retained by a coalition of environmental groups including the Harpers Ferry Conservancy and the National Trust for Historic Preservation to evaluate the historic properties the groups believed that the State’s consultant failed to identify in the initial round of Section 106 consultation. Between 2001 and 2008 I did many Section 106 projects for FCC licensees and I had been working on histories of postwar telecommunications networks.[2] By the time I had been brought into the Lamb’s Knoll project I was sensitive to the historical significance embodied in telecommunications facilities like the repurposed fire lookout tower and the Cold War facility.

Interchangeable Parts: 10 Years Later

Last week I attended the Vernacular Architecture Forum conference in Washington. Conferences are great events that give consultants (like yours truly) a chance to speak with colleagues from around the country. At the banquet I had a long conversation with someone who does cultural resource management work out in the Pacific time zone. We commiserated about the ranks of CRM firms who send out archaeological technicians to identify historic buildings and landscapes. We lamented the lack of regulatory oversight by federal agencies and state historic preservation offices to ensure that historical research and analysis were being done by historians and not archaeologists being kept billable by mega consulting firms.

Our exchange brought to mind similar conversations I had carried out with the late Ned Heite. Some of these took place on email lists like ACRA-L. One memorable one took place in June 2000. Ned aptly titled it “Interchangeable parts. Ned had responded to one of my posts, which read in part:

As I sit here looking through yet another Section 106 report on above-ground architectural resources prepared by archaeologists and rejected by a SHPO, I wonder when anyone in this industry is going to understand the “American System.” Interchangeable parts are things that are bulk or mass-produced that can be swapped out for in-kind identical parts in a tool, machine, whatever. If you’re going to apply the interchangeable parts model to the CRM industry, swap parts in offices, jobs, etc. with like parts. Don’t send archaeologists out to do what an architectural historian should do. After all, when your brakes go on your car, you’re not goign going to replace them with spark plugs, now are you?

Ned’s post read:

Bravo, David. As one who is “certified” by the SHPO in all the disciplines, I second your statement. By coincidence of employment, I have managed to push all the buttons for the Secretary’s standards. This does not, of course, mean that I know what I am doing.

Along those same lines, one of my pet peeves is the portable historian. When the weather turns bad, the state archives are flooded with field techs and others, who are supposed to be doing historical background research. Most of them haven’t the foggiest notion of historical research or the history of the locality.

Local history research is an arcane field, best left to people who are specialists in a very narrow geographical area. Yet CRM firms routinely dispatch unqualified staff to research the background history of places they can’t even pronounce!

The standards should be tightened, exponentially, and the historical background should be mandated to be done by a person with local expertise, who is also recognized as a competent CRM historian. And remember that a CRM historian is a very different creature from a kid with a fresh MA in some kind of generalized history.

Little has changed in the 10 years since that exchange. Large engineering companies with cultural resource management divisions continue to deploy teams of archaeologists to do historians’ work. I recall observing the archaeologists return from the field and in mixed horror and amusement watched them spend countless hours (and clients’ dollars) trying to match fuzzy photos of buildings with what they could find in Virginia and Lee MacAlester’s generic Field Guide to American Houses.

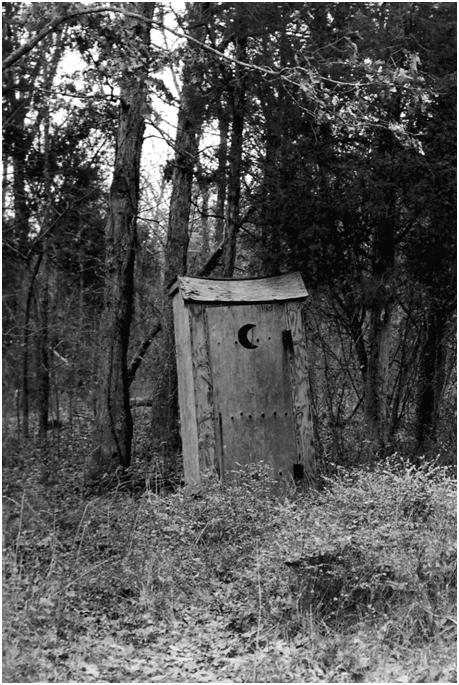

I still have the wonderful photo of a Prince William County privy that one archaeologist (who did not do the fieldwork, but who was given a stack of photos to describe) characterized in her report as a “desk.”

History in the crapper: one archaeologist’s “desk.”

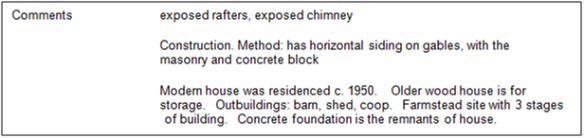

Among some of the choice architectural descriptions penned by archaeologists are these:

Making 1953: Elgin Park, Pennsylvania

I saw this on ABC News this evening: Nostalgia+Creativity=Elgin Park.

Web History

Last week I distributed Historian for Hire’s first e-update. In the one-pager I mentioned the first professional Web site I created. Designed for Cultural Resource Analysts, a cultural resource management company in Lexington, Kentucky, the site went live in January 1996. My local files for time I maintained the site have long since succumbed to data rot but the good folks over at the Internet Archive have it preserved on their servers. It’s not pretty nor is it flashy, but it did the job. And, if you surf through the company’s current Web site structure you will see that despite almost 15 years and multiple webmeisters, the basic architecture that I designed remains intact.

Last week I distributed Historian for Hire’s first e-update. In the one-pager I mentioned the first professional Web site I created. Designed for Cultural Resource Analysts, a cultural resource management company in Lexington, Kentucky, the site went live in January 1996. My local files for time I maintained the site have long since succumbed to data rot but the good folks over at the Internet Archive have it preserved on their servers. It’s not pretty nor is it flashy, but it did the job. And, if you surf through the company’s current Web site structure you will see that despite almost 15 years and multiple webmeisters, the basic architecture that I designed remains intact.

CRAI’s owner Chuck Niquette advertised the new site in a post to a young professional organization’s public listserv, ACRA-L. A few days later I registered the company’s new domain name and moved the site off of my grad school Internet account held at the University of Pennsylvania. The screen capture shows the front page in early 1996 and below is CRAI President Chuck Niquette’s announcement of its birth:

Hamlets 1, County 1: Local Landmarking

In January I wrote about the difficulties of local designation in the aftermath of chairing my final Montgomery County Historic Preservation Commission hearing. Last week the newly constituted HPC continued the worksession begun in January and concluded that the two proposed historic districts did not meet the County criteria for designation. The hearing and HPC’s decision was reported in this morning’s Montgomery Gazette: Claggettsville Out of Running for Historic Designation. Last week’s worksession stretched well into the night and was stopped before the HPC was able to complete its consideration of all of the properties proposed for designation; the worksession continues next week (10 March 2010).

Although the Gazette reporter touched on many of the key issues, she failed to broach some of the more difficult problems facing the HPC: incomplete research and the troubling failure by County historic preservation staff to disclose the fact that one of the historic districts, Clagettsville, had been evaluated by the State Historic Preservation Office in 1991 and found to not meet any of the Criteria for Designation for listing in the National Register of Historic Places. According to the DOE form, apparently completed by then-Montgomery County Planning Department historian Mike Dwyer, “The crossroads community of Claggettsville has undergone numerous alterations and has many intrusions. It no longer conveys the sense of a 19th and early 20th century village and lacks sufficient cohesiveness to be considered a district.” The February 18, 2010 HPC staff report prepared for last week’s worksession mentions the MHT document but fails to include any of the language in the MHT document. Furthermore, contrary to my request to HPC staff that links to the MHT documents (post at the MHT/MD Archives Web site) be included with the hearing material, the staff elected to let stakeholders know that the materials are available and left it up to individuals to find the materials on their own. There are some very serious implications for the property owners in the two historic districts if they are designated locally and found by MHT to be not eligible for listing in the National Register of Historic Places. Chief among the implications are the benefits of designation touted by historic preservationists vis-à-vis state historic preservation tax credits. If a historic district is not listed in the National Register or (and this is important) is not determined eligible for listing in the National Register by the MHT, then property owners are not eligible to receive state historic preservation tax credits.

Among the continued concerns I have that remain from the January hearing and its supporting documents are the ways in which HPC staff rely on National Park Service/National Register of Historic Places guidance and standards only when it is convenient to support their positions (sometimes demonstrably incorrectly as with some of these designation documents) but when individuals attempt to bring in the NPS/NRHP literature HPC staff takes the position that the NPS/NRHP materials are informative only and that Chapter24A criteria are the only applicable standards.

Last year Councilmember Mike Knapp introduced legislation to amend the County’s historic preservation law (Chapter 24A) . I think with the Upper Patuxent Master Plan Amendment working its way towards the Planning Board and Council there is an opportunity to revisit amending Chapter 24A to open up the designation of historic districts to more property owner involvement, i.e., provisions for owner consent by establishing a percentage threshold of consenting owners within the boundaries of a proposed historic district to enable a historic district designation to move beyond the HPC.

More on this next week.

Confronting the Covenants: Hidden Racism at Home

NPR’s Morning Edition this past Sunday included a segment on racially restrictive deed covenants <http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=122484215>. NPR noted that the covenants were not legally enforceable and that they were widespread throughout the United States.

Robert Fogelson, author of Bourgeois Nightmares: Suburbia, 1870-1930, discussed restrictive covenants at length. Other authors on the history and sociology of American suburbs also have written on restrictive covenants. In my work over the past 25 years I have done projects in quintessential American suburbs that involved primary documents research, including land records (deeds, etc.). These communities include Shaker Heights, Ohio, and Chevy Chase (Maryland and the District of Columbia).

I live and work in Silver Spring, a Washington suburb. My subdivision, Northwood Park, was created in 1936 and my home was built in the subdivision’s first year of existence. When we bought the house in 2002 our deed contained all the expected legalese, along with the clause, “Subject to covenants and restrictions of record.” It wasn’t until I began doing some research on the history of our subdivision that I discovered that some of those covenants and restrictions prohibited anyone of a “race whose death rate is at a higher rate than that of the White or Caucasian race.” Put in place in a stand-alone document recorded in Montgomery County land records, they were executed, “For the purposes of sanitation and health, and to prevent irreparable injury to Waldo M. Ward [the majority landowner] … and the owners of adjacent real estate.” Garden Homes, the company selling the lots and homes, executed the covenants almost six months after the first sales and signatories to the covenants included all of the people who had bought property up to that point.

Northwood Park is the subject of my paper in progress, “ The Greatest Publicity Stunt Available to Developers”: Washington’s 1939 World’s Fair Home.”